Union Jack’s

(Union Jack’s Public House, Ballston Neighborhood, Arlington, VA. Photo Union Jack’s.)

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge left Buckingham Palace by helicopter to commence their married life. At least that is what the Beeb said this morning. I breathed a sigh of relief that I am now able to let the tangled affairs of the Royals slide back into my brain attic where they can remain, un-contemplated, until the next scandal or moment of monarchial singularity.

I have to say that it was a wonderful encounter with the Windsors, though. Or the Battenberg-Windsors, which is the surname that the father of the groom and his ex-wife entered in the marriage register long ago. The new Royal couple got three new titles for the occasion as best I can tell.

I would style myself as the “Duke of Socotra” if I could, and it occurs to me that I might, like the Dauphin in Huckleberry Finn.

Charles has become the longest-serving Royal in the on-deck circle in history, and I saw Ms Parker-Bowels giving him the business, or appearing to, in the high-sided limousine as they arrived at the Abbey.

The Queen, bless her, was dressed in a conservative frock the color of the bottom of a lemon merengue pie.

I have no idea why we Americans are so enamored of the marriages of the Royal. It is sort of a chick thing, I think, or at least that was the impression I got when I walked into the bar at Union Jack’s just after 0530 yesterday morning and saw all the hats and tiaras worn without a great deal of irony.

But I am getting ahead of myself as usual. Despite my personal relationship to the father of the groom, more of that anon, I probably would have slept in on Friday morning if Mary-Margaret had not won tickets to attend a promotional event at the local British-themed pub Union Jacks. We had attended the National’s game downtown the night before, and the late return from a surprising victory over the Mets made sleep short.

It was sort of neat that the marriage was not an uneasy compromise between the East and West Coasts of the United States like the Superbowl or the NCAA Men’s Final basketball game. For this moment, at least, London was once more the center of a world on which the sun never sets.

There is a day coming when the past-tense will apply to Washington and New York as well, but not just yet.

Anyway, in London the ceremony was scheduled to start precisely at 11:00, and walking the cat backward, Mary-Margaret decreed that we should meet in lobby of Big Pink at 0520 to proceed to the event and be in our places in time for the ceremony.

She had four tickets, and I was the lucky “B”-list attendee. Mary-Margaret’s consort was off looking at the second-to-last Shuttle launch down on Florida’s Space Coast, the penultimate event in America’s going-out-of-the-spaceship business, and I was the lucky beneficiary.

They say the Shuttle is the most complex moving thing the human race has designed, except for marriage, and as it turns out, the launch was postponed even though everyone had shown up on time. I was the lucky beneficiary of the fourth ticket, along with Marty-1 and Death Junior.

It was still dark as I donned white duck trousers, white buck shoes and a sedate clip-on bow tie with a boldy-striped Brooks Brothers shirt covered by a sedate blue blazer. I wanted to show respect, rather than shrugging on my jeans and a t-shirt.

Memories of another Royal wedding flooded back as we met in the lobby. Marty-1 was wearing a full-on hat, a wildly improbable inverted mushroom of hot pink floral color. Mary-Margret was stylish in a dark tailored silk pant-suit. Death Junior, as you know, has moved out of the building, but secured parking at her employer’s Ballston location and was walking from the funeral home.

I decided to drive myself over and park at the office. I was going to wind up there anyway, and Union Jack’s is just a couple long blocks away. It was a pity Willow was not the destination. I know owner Tracy O’Grady could have done it up right, but as a good Irishwoman, I suspected she was ignoring the whole enterprise.

Most of Ballston was just coming alive. I had to use the card access to open the big segmented steel door to the garage, and popped up through the Westin Hotel exit. Crossing Wilson Boulevard I saw that a satellite truck was parked in front of the bar, the control room illuminated. I stocked up on cash from the e-Trade bank in the lobby, and walked past a Union Jack employee clad in a red jacket and busby, like a rental version of the guards at Buckingham Palace.

We could have come earlier. Apparently the doors had opened at 0500, and you could tell the available staff was a little shell shocked, since last call had only happened a few hours earlier. Every table was taken, mostly filled with women, and most of them in hats.

A perky young woman near the door indicated that non-radio attendees were sequestered in the front parlor, with special seating and a vast buffet offering a Big English Breakfast with beans, bangers and squeek. Not to mention Pimm’s Cup, a real BBC correspondent, 25 big-screen TVs and Mix 107.3’s Jack Diamond in the Morning, live and broadcasting in person.

It was good that Death Junior had been in position at the bar. She glowered at a couple women in spring dresses and elaborate millinery, holding them away from a couple seats in front of the beer taps at the back bar.

(Kate Middleton and some guy stand at the altar at Westminster Abbey. Photo Socotra.)

Notables were arriving by long black cars at the Abbey as I contemplated whether to have coffee and wake up, or just surrender to alcohol and the moment. As I watched the magnificent uniforms, and the astonishing headgear, I was drawn back to the summer of my own marriage, and the costume-dress of my own uniform and that marvelous dress of white.

That was the connection I have with the Prince of Wales. He proposed in February of 1981, and the world began to buzz with the anticipation of the Wedding of the Century. I proposed the week I got out of Korea, 36 months out of America, and finally ready to make a commitment.

Charles and I shared that sentiment. He and Diana were wed a few weeks after I was, and I am

The bride I could see over the beer taps looked magnificent, and everyone commented on how lovely Kate looked in her dress. Tim the bartender helped my decision. “This is a bar, not a coffee house. We have one machine that doesn’t do much more than your Mr. Coffee at home. Sorry.” He shrugged and smiled.

“Make it a Bloody Mary, then,” I said. I looked up at the spectacle on the screens all around, a hall of elaborate electronic mirrors and soaring gothic arches.

Mardy-1 opted for a mimosa. Death Junior tossed her newly-blonde locks and stayed sober. She got up to make a run at the buffet. “If my phone rings, it means someone died. I have the duty today.”

Mary-Margaret leaned over: “There are supposed to be two billion people watching the ceremony!”

“Two billion,” I said. “That is a hell of a number.” I had another couple drinks as we watched the priest and the ring and the singing and all the hats, both there and at Union Jacks. Then, when The Duke and the new Duchess emerged from the Abbey, I slipped a couple twenties to Tim, and walked down to the office to start the day.

The Royals would be off on Honeymoon, leaving the palace by helicopter, and I had to get ready to go to Detroit.

(Party at the remote viewing of the Royal Wedding. L-R: Socotra, DJ, MM and M-1. )

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicocotra.com

Royal Pain

(Us Marines stand with captured Korean battle flag, 1871, near present day Inchon.)

Mac and I paid Elisabeth-with-an-S and she gave me one of those smiles that keeps me coming back. We walked out of Willow’s rich wood bar and down the steps onto the brick patio.

“My usual parking place,” said the Admiral with a note of pride. The sleek Gold Jag was directly across from the gate in the black railing that separated the Willow patio congregants from the pedestrians hurrying to and from the Ballston Metro Station. “Let me give you a ride down to the American Service Center to retrieve the Hubrismobile.”

“I can walk, really,” I said. “I need the exercise.” I also wanted a minute to figure out which of the poor melting credit cards in my wallet I was going to cycle the repairs on to. That was a constant royal pain. But Mac was insistent, and I relented immediately.

He unlocked the pristine sedan and I plopped myself into tanned pale leather of the right hand seat. “So American citizens are butchered by the Koreans,” I said, “And what was the response? We used to be a little more muscular in our overseas relations. At least after the matter of the Barbary Pirates was settled with the establishment of a Navy.”

“That adventure also required the rescue of an American ship and crew.”

“Oh, yeah,” I thought. With everything else going on in modern Libya it was easy to forget that Tripoli had been the source of the first major embarrassment of American arms overseas, and the first place the Stars and Stripes were raised on foreign soil. “Was it the Philadelphia that ran aground and got captured in Tripoli Harbor?”

The Admiral nodded. “There is a tradition as old as the Service: you get your ship back. The Berber pirates hauled the ship off the reef and anchored her to serve as a floating battery. Steven Decatur led a cunning party that managed to get close enough to board and overcome the Berber guards and burn the ship, sinking it.”

“So the principle is that a nation’s warships remain their property, regardless, right?”

The Admiral smiled as he skillfully swung away from the curb. “That is why Pueblo is still a commissioned ship-of-the-line.”

“I know we used to care a lot about it. I have some declassified OXCART imagery that shows her in Wonsan Harbor. She was on the priority collection list for COMIREX for the satellite pictures, too. So what did President Johnson do about the killing of the Americans and the destruction of the General Sherman?”

(A-12 OXCART (CIA Version of SR-71 Image of Pueblo in Wonsan Harbor 1968.)

The Admiral swerved a bit to avoid a Lance Armstrong wannabee who was hurtling through a crosswalk near the International House of Pancakes. “He did what any President of a certain era would have done. He sent in the Marines to punish people who were pains in the ass.”

“Is that what opened up Korea to trade?”

The Admiral put on the blinker to turn right at Quincy and head down to where the American Service Center is reinventing itself from a low-rise to a high-rise structure.

“No, that happened later. Actually, it took five years for the Marines to get there. The Navy landed nearly 700 men landed near what we know now as Inchon. It was partly to resume trade talks, but obviously robust enough to avenge the insult to the Flag. The Koreans again resisted, but in two days of heavy fighting, the Marines destroyed five forts and inflicted as hundreds of casualties on the defending Koreans, while suffering only three casualties of their own. A Marine private killed the Korean commander, General Uh Je-yeon, and took his flag.”

“Is that the one that wound up with all the other captured banners at the Naval Academy?”

Mac deftly swung the Jag down the alley behind ASC. “Yep, the very one. I can wait until you are sure the Hubrismobile is ready.”

“Thanks, but no, I can hoof it back to Big Pink if it isn’t. For the amount of money I am paying to have the rear seats headrests adjust so the top works again, they will probably be happy to give it back.”

I opened the door to confront the highly-skilled technical experts, mentally vowing never again to own an elaborate piece of German rolling stock. Something occurred to me, though. “None of this history is ever forgotten over there, is it?”

Mac shook his head. “No, they have long memories, though what they remember is not necessarily the truth. Great Leader Kim Il Song always claimed his great grandfather Kim Ung U had been a ringleader in the killing of the General Sherman’s crew. Made the whole Kim family big heroes.”

“They claim that when the Dear Leader, that little shit, was born on Mount Paektu there was thunder and lightning and the iceberg in the sacred pond emitted a mysterious sound as it broke and bright double rainbows appeared from it.” I waved my hands in wonder at the miracle.

Mac pursed his lips. “He was most likely born in Siberia, where his father was in exile at the time, a pet of the Russians. I have heard that Pyongyang’s Korean Central News Agency reported that Venus shed an unusually bright light above the sacred lake when Kim Jong-un was announced as the new King.”

“They have a national pattern of mass hallucination. I have no idea what they are going to cook up for the newest Kim to take the throne. When I was in Pyongyang,” I said, holding the door, “The delegation agreed to go along with the delusion and just believe impossible things before breakfast. The Clinton Administration thought you could negotiate in good faith with them.”

“No,” said the Admiral with a smile. “Every resident of the White House has to learn that for himself. You can’t trust them further than you can throw them. Bill Clinton got rolled when he had a chance to get the Pueblo back and he didn’t.”

“They must think we are chumps, don’t they?”

“I am not sure they are wrong,” said Mac. “Next time at Willow for the Damage Assessment story. That was the high point of my five and a half years at DIA. We had five copies of the final report, and I think they have all been destroyed now.”

“Why would anyone destroy them?”

Mac shook his head. “Some people don’t want to remember.”

I closed the door, careful not to slam it, and waved as Mac roared off down the alley. I hoped the car was ready. The next morning was going to be a royal pain as it was. I had accepted an invitation to start getting drunk at 0530 and watch some couple in England tie the knot.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

The General Sherman

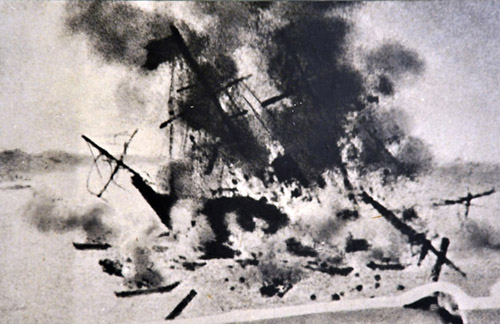

(The SS General Sherman burning. Photo courtesy of the DPRK Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum.)

Elisabeth-with-an-S came by, topped up my Grenacha with a practiced twist of her lithe wrist and kept moving. The belt of extraordinarily intense storms that scoured the South were passing through, and the bar of the Willow had filled up with people who would have been sitting outside, enjoying the warmth.

“Not bad for an attorney,” I said, since she is admitted to the bar in two states, though of course I have been in bars in all of them. She turned and stuck out her tongue and looked questioningly at the Admiral, who put his hand over the top of his mostly-drained Virgin Mary.

“None for me,” he said. “I am good for now.”

“You are always good,” I said. “I can finish this one and be on my way. The Hubrismobile is going to cost $1,200 to have the rabbit ears taken down.”

Mac nodded. “The Jag always costs a thousand when I take it in, no matter what I have done to it.”

We commiserated at the challenge of driving really hot cars for a moment and I regained my train of thought and picked up my pen. “Every administration has to deal with the Koreans, and they all think it is easy, and all of them get taken to the cleaners.”

“Cagey bastards, you are absolutely right.”

“So the latest is that the parts of the DPRK are expected to run out of food in less than two months due to a poor harvest from the savage winter.”

“I would be cautious about reports of dire food shortages in the North,” said Mac. “I suspect the communist state is exaggerating the problem to win assistance from the West, and the Administration hasn’t really internalized how focused those people are. I was the PacFlt N-2 until 1966, after all, and even if Indochina was our primary focus, there was always something going on there.”

“I want to hear about the Damage Assessment on the Pueblo,” I said, “and if the Russians put them up to it to get the KW-7 code machines.”

“I think so,” he said carefully, “but as with everything the North does, there are several layers to consider.”

“I had no idea how far back our history with them went. The Opium Wars with the Chinese are about all that anyone considers about the West in Asia. I knew about the Black Ships and the arrival of the Americans in Japan to open up trade. I didn’t know much about the struggle to open up Korea.”

Mac smiled. “The story of the General Sherman is why Pueblo is where she is right now, and why the Naval Academy had to give back the flag.”

“We never remember our history, but some people do,” Mac declared. “See, the whole thing is about perspective. For those who live in the region, the term “Far East” is a misnomer. It is neither far, nor east. It is the center.”

“That is what I thought when I lived in Seoul,” I said. “I always thought I could hear the whisper of North Korean paratroopers dropping out of the sky. They used those AN-2 Cubs, the fabric-covered biplanes, to deliver special operations forces. The airplanes were too slow and too radar transparent for radars designed to detect hi-performance jets. It was spooky.”

“Always has been,” said Mac. “Just after the Civil War, an ex-Confederate privateer passed once more into private hands. Re-christened the SS General Sherman, she moved on to become a ship of destiny in the Far East, a sort of sister ship to Pueblo.”

“I think I recall some of that,” I replied. “The West was eager to open up Asia to trade. Commodore Matthew Perry had pioneered the concept of forced entry when he sailed up the Tokyo-wan and anchored his Black Ship squadron off the Imperial capital of Edo on July 8, 1853. The cannons were not used in any manner except thinly veiled threat, and resulted in the Treaty of Kanagawa that opened Japan to the world.”

“Well recalled,” said Mac. “They tried the same thing in Busan in the south of Korea the next year, but the Civil War got in the way and no one got back to the idea of opening up Korea until after Appomattox.”

“I imagine the Koreans were a little nervous after the Brits took Shanghai and founded Hon Kong.”

Mac nodded. “The British trading concern of Meadows and Co., based in Tientsin, China, arranged to dispatch General Sherman to Korea to commercially replicate the success of Commodore Perry thirteen years before. She carried a cargo of cotton, tin, and glass. She also mounted guns the Navy had provided, and was intended to offer both promise and peril to the Court of Chosen.”

“So what happened? I gather it did not go very well.”

“No, it didn’t. In August of 1866, General Sherman entered the mouth of the Taedong River on Korea’s west coast, where a representative of the King informed Preston that his country did not trade with the West, and the presence of the General Sherman was unwelcome. The depth of the river would normally have precluded further navigation, but it was swelled with unseasonable rain. At two points he was informed that a decision on trade would have to await the blessing of higher authority. Captain Page thus proceeded onward up the river, past the Crow Rapids to the Keupsa Gate of Pyongyang, where falling water grounded the ship.”

“Not a good place to be,” I said, finishing my wine.

“Very bad. The only accounts of what occurred next come from the archives of the Korean Court. At that time, the Hermit Kingdom was ruled by the Price Regent, the Daewongun. When word came that foreigners were in the river, he sent orders for the ship to depart immediately or all the crew would be killed. General Sherman was stuck, literally. The Koreans believed they had an American Navy ship in their midst, and had little interest in the niceties of its commercial flag. A four-day battle ensued, with the Westerners and their Asian crew giving a good account before they were slaughtered. Records say that two attempted to survive by using smiles and soft words, but they were hacked to pieces with the others who fought, and the bodies were trampled and then burned on the shore.”

“So that is celebrated as a great victory over the Americans by the North Koreans?”

“You got it. Goes back nearly a century before the Korean War, which is the center of their universe and largely forgotten here.”

“Damn,” I said. “That would have been useful to know. And there is the latest crisis. They say the crop yield has fallen by a half and that some people were already eating grass, leaves and tree bark.”

“They say a lot of things,” said Mac, and he signaled to Elisabeth for the check.

(Pueblo Capture Commemorative stamp.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Damage Assessment

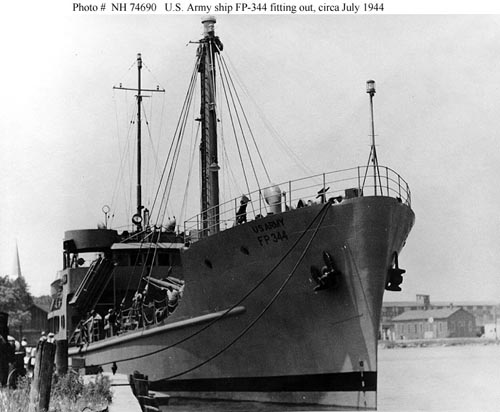

(USS Pueblo, TAEG-2 as she appeared when commissioned in 1944. US Army Photo.)

I always get a little unhinged in time when I hang out with Admiral Mac. His merry eyes dance across the decades, sweeping me out of this bold new decade in a slightly threadbare almost post-American century.

We are hanging in, but barely, and at some point the music is going to stop and we will look around as the lights come up and the nightclub is going to look as seedy as old Detroit. I have tired to be kind to my old hometown, tough a little fascinated by what has occurred to a once vibrant place, and if you want to take the extended tale as a metaphor for what happens when you stop paying your bills, personal or civic, that is entirely up to you.

Anyway, I asked Mac about his last big job in the Navy.

“I retired in December of 1971,” he said firmly. “I was Chief of Staff of the Defense Intelligence Agency. In those days they had a firm rule about having the three major military departments represented in the leadership. Army had the Director, an Air Force officer was the Deputy position and I was the two-star CoS for Navy.”

“That was after the damage assessment on the capture of the USS Pueblo? That must have been fascinating.”

“And grim,” said Mac.

I looked at my notebook to see where I might insert the notes. I had jotted down the series of discussions about the legendary Marty Hurwitz, who I knew as the all-powerful director of the General Defense Intelligence Program, and whose job, in one of those accidents of history, I had in a much later incarnation.

“We talked about Marty last fall. What was the story, again?”

“Marty was an Army officer who came to work for me as Director of Plans. He had been in Germany, and the service has ordered him in to relieve the desk officer responsible for Israel.”

“So how did he get to you in the budget shop?” I asked, marveling that Mac and I shared the arcane art of the DIA budget program thirty years apart.

“The leadership saw his name and couldn’t tell if he was Jewish, and when they asked, the Army said it was none of our business. So they changed the orders and put him in charge of the Planning, Programming and Budget system. He got out of the service and stayed there for 25 years.”

“I remember,” I said. “Everyone was afraid of him except Lew Prombane, the Comptroller. I worked with him after I retired. They were Titans, I’ll tell you.”

Mac laughed. “They were just a couple kids, Lew was coming from a junior Navy job and Marty was still wearing railroad tracks. But then the North Koreans seized the Pueblo and I had a new job and a really important one, since Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms was intensely interested in what had been compromised in the capture.”

“That was in January of 1968, right? I told my buddy the Lawyer we would be talking about it and he said he had a picture of Pueblo in his USS Princeton cruise book, taken in December of 1967 before she got underway for the Sea of Japan. It is maybe the last picture of her taken while still in American hands. He scanned it and sent it to me.” I pulled it out of my notebooks and passed it over.

(Last picture of USS Pueblo (extreme left) with an American Crew, December, 1967. Photo courtesy SerraLaw.)

“I have seen more pictures of that ship than I ever need to,” said Mac. “We actually recreated the ship to figure out what had gone missing on us, and it was a lot.”

(KW-7 Crypto machine similar to the one on USS Pueblo, TAEG-2. Photo National Cryptlogic Museum.)

“Do you think the Soviets egged the Koreans on to get the crypto gear on board?” I asked. “ The KW-7 encyphering equipment, paired with the codes that jerk Walker was giving them, would have permitted the Russians to read all the secret-level message traffic. Vietnam was at its height, which is why John Walker should have been hung.”

“Yes, and I think, Yes.” Mac took a sip of his drink. “There were a lot of strange coincidences in 1968.”

“There is even a Detroit angle,” I said with a note of triumph. Mac looked at me skeptically.

“1944,” I said. “Pueblo was built at the Kewaunee Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in Wisconsin as an Army logistics ship. To get out of the Great Lakes she would have had to steam through Mackinaw to Lake Huron, down the east coast of Michigan, and then through Lake Saint Claire through the Detroit River. Maybe she made a port call there and the crew went ashore and got liberty in the Motor City while it was humming, and the war plants were operating around the clock.”

Mac smiled. “She was commissioned in New Orleans, so my guess is that she came south to Chicago, then passed through the Chicago Sanitary and Ship channel to the Mississippi.”

“Dammit, there is Chicago again, stealing Detroit’s glory.”

“I got commissioned in Chicago,” said Mac, “When Rush Street was still off limits to navy personnel. That is one hell of a city.”

“I know,” I said wistfully. “It is still alive.”

“But do you want to hear about the damage assessment? If you do, we have to talk about the armed merchant ship General Sherman, and the battle flag of Korean General Uh Je-yeon, and then how the Pueblo got from Wonsan on the East Coast to Pyongyange on the West.”

“Do the north Koreans have a shipping channel I don’t know about? They couldn’t have got her underway again, could they?” I asked with a smile.

Mac just smiled right back and I opened the notebook to a new page.

(People’s Museum #5 in Pyongyang.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Garnacha Blanca

(Admiral Mac is out and about again in the Spring weather. Photo Socotra.)

They say there is truth in wine, and I am a fervent believer in the principle. I managed to extricate myself from the office and walk under the delicate blue skies and head down to the Willow around the cocktail hour.

From down the block I could see the Admiral’s gold Jag parked at the curb in front of the restaurant, and I picked up the pace so I would not keep him waiting. I strode into bar and saw a hole where Old Jim normally anchors the bar. That was unusual, but he has been threatening to find a new place to drink, since newcomers are crowding out the regulars.

“It’s like what Yogi Berra said,” he grumbled, last time I saw him. “No one goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”

John with an H was down the bar and he waved, and the Admiral extended his hand as I pulled the stool out next to his.

“I have a question for you,” he said, “And a couple obits for the Quarterly.”

I smiled. “That is unusual, but shoot.”

“A woman named Phyllis is driving us crazy at The Madison. She seems to want to know everything about the United States Military, and has settled in on retirees from the various Departments to pepper us with questions. Last week it was the ranking of Navy medals and awards. I told her I had no idea.”

I mentally started down the line, Navy Cross first, of course, but the Admiral waved dismissively.

“She got around to the portentous matter of aircraft carriers the other day, and since I knew we would be at Willow this evening for the first outing of this newly minted Spring, I am just going to ask you her latest question. What about the color of the flight deck Jerseys?” he said. “She is intrigued by why the people who work around the airplanes have different colored shirts and helmets.”

I nodded and sipped some of the Garnacha Blanca that Elisabeth-with-an-S poured with deft motion. She glided away with graceful elegance, hurrying a bit, since the marvelous weather had caused the patio to fill up and the staff was stretched to keep everyone’s glasses filled.

“Elegant woman,” said Mac as she glided behind us.

“No kidding,” I said. “You have not lost your eye for the ladies.”

“Nope,” said Mac. “It was a long winter but I feel pretty good and have got the new meds under control. Life is good.” He took a long sip of his Virgin Mary and smiled with contentment.

“Let’s see,” I said, furrowing my brow. “Red shirt means ordnance, Yellow are plane captains, Green is maintenance, white is for the Landing Signals Officers, Brown is for maintenance. And Purple is aviation fuels.”

“A sort of Naval Aviation Purple gang?” said Mac, grabbing my pen to write down the colors and definitions on a napkin.

“We called them Grapes,” I responded, “and that is something you would not have done to the Detroit Purples.”

“You know my daughter is in Kalamazoo,” he said. “She has liked the stories about the Motor City. It is a sad tale.”

“She would have been in Purple Gang Turf, east of US-131,” I said. “But there are mixed reviews on that score,” I said. “Some people like it and some think I am fixated on something that doesn’t exist and really never did. I am still working out how I feel about it and wanted to have a good baseline before we get there this Sunday. I have been driving around the city in the morning, looking at the places I have been talking about.”

Mac looked at me curiously, glasses up on his forehead.

“Google Maps,” I said. “Type in a street address and then zoom in and you go to the street-view mode. When you are there on the street, you can zoom along with the mouse, advancing to each point the little Google car drove, taking pictures.”

Mac did not seem overly impressed. Perhaps having been born the very year that the Purple Gang graduated from petty theft to armed robbery had provided enough in the way of technological miracles that one of the latest iterations did not surprise him.

“I went to the Hastings Street neighborhood yesterday, to see what they might have seen long ago. Nothing there. Graffiti on the abutments to the railroad bridges, then nothing except a couple abandoned factory buildings. I flew down to the intersection at Piquette and turned right to where the original Ford factory was. That is there, but nothing else. No stores, no houses, no nothing.”

“That is what happens when a city hits the skids,” said Mac. “The streets get dangerous and the families leave. The riff-raff takes over and it gets worse. The businesses can’t survive, and they close, and then there is nothing but drugs and prostitution, and eventually the houses start to collapse and there are only the lost and dangerous and deranged left who can’t escape. Eventually the buildings collapse or are bulldozed if the city can afford to do it.”

“It is certainly safer to have the Google people drive it for you,” I said. “The neighborhood across from where I lived in Palmer Woods went exactly that way. We had a private renta-cop patrol, and I imagine they still do, if they can afford it.”

Mac nodded at the obvious. I pressed on, though. The whole Detroit thing has me pretty worked up, as you can tell. “The Chaldeans east of Woodward were not so lucky. That area was called “State Fair,” since it butted up to the Fair Grounds. There is nothing there now. The trees have all grown together over the roads and the grass is up to your waste. The Hookers used to parade along Woodward Avenue there, and take their tricks back to the empty houses, and with the exception of a couple Arab coffee houses, that is all that remains.” I took a picture out of my notebook that I scooped off the web. “This is one house that is still there. Parts of the State Fair look like you were standing Up North.”

(State Fair neighborhood hanger-on between 6 and 8 Mile. Photo Detroitblog John.)

Mac nodded, pushing his glasses up on his forehead again to see. “I don’t use them to read the paper,” he said.”

“I wish,” I replied touching my peepers. “I am getting blind as a bat.”

Mac was ready to move on. “We lost a retired Navy Captain at The Madison the other day. Good guy, I think, but he had dementia the last eight years that I knew him. Harding was the name. He was CO of the NELC in San Diego. Still had license plates on his car that said exactly that.”

“NELC?” I said, enjoying my Garnacha.

“Naval Electronics Laboratory Command on Point Loma,” he clarified.

“Sure. Now I get it- it was NOSC when I knew it, Naval Ocean Systems Command, then NRaD and goodness knows what now. I sure would have liked to get a government job there and just lived on Point Loma and let the East Coast slide into the sea.”

(NELC at Point Loma around the time CAPT Hastings would have been commanding. US Navy Photo.)

“Nice place,” said Mac, then pointed at the notebook next to my elbow. “So, did you have questions for me?”

“We never did the Pueblo, I think. Didn’t you do the damage assessment on what the North Koreans got off of her when they hi-jacked her?”

“Yep. That was the last big deal.”

“Wasn’t Wanda your admin assistant? She has been the Director’s Secretary for years and years.”

“Yes she was. She was a pert little thing then, dark bobbed hair and flashing eyes and she wore mini-skirts. She was quite the looker.”

“Still is,” I said, and reached for my pen.

Tomorrow: Pueblo and the Penobscott

(People’s Museum #5. Photo courtesy DPRK.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Whiskeytown

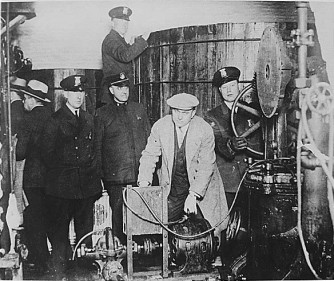

(Detroit’s Finest break up a Whiskeytown liquor operation.)

Elliott Ness, my ass.

It is enough to make a Detroiter spit. That grand-standing son-of-a-bitch was charged with taking down Al Capone, and as head of the 300-man Untouchables, conducted a bunch of high-profile operations against the mobster.

Elliot was never one to hide his brilliance under a bushel basket, and that may be why the Roaring Twenties has a distinctly Chicago feel. Maybe it is a combination of Elliott’s self promoting autobiography and the other grand-standing son-of-a-bitch of the time, J Edgar Hoover, who trumpeted the success of his G-man Melvin Purvis when they gunned down John Dillinger at the Biograph Theater in the Lincoln Park neighborhood.

Chicago got all the great press, and the Tommy Gun is the icon of the age there, but for Pete’s sake, it was Detroit where the booze was flowing and that is where the money was. It was a bonanza, bigger than the automobile industry. Three quarters of all the illicit hooch crossed into the US along the 30-miles stretch of the Detroit River from Lake St. Clair down to Lake Erie.

“Q: Where in Detroit can you buy liquor?”

ANSWER: In open saloons, restaurants, night clubs, bars behind a peephole, dancing academies, drugstores, delicatessens, cigar stores, confectioneries, soda fountains, behind partitions of shoeshine parlors, back rooms of barbershops, from hotel bellhops, from hotel headwaiters, from hotel day clerks, night clerks, in express offices, in motorcycle delivery agencies, paint stores . . .importing firms, tearooms, moving van companies, spaghetti houses, boardinghouses, Republican clubs, Democratic clubs, laundries . .”

In 1918, before prohibition, Detroit had 2,334 liquor serving establishments. During the height of enforcement in 1924, the number had soared to 15,000 establishments that dispensed alcohol. In that year alone, $30 million dollars worth of Canadian liquor was smuggled across the border with an estimated street value in the States of $100 million.

The gangsters in the Motor City- maybe we should call it “Whiskeytown-“ were so tough that Al Capone wisely decided to draw the eastern line of his territory at US-131, the north-south road in west Michigan. It passes through the Little Town By the Bay way up North, and our house there is on the west side of the road, which would have placed us in Capone’s territory.

Accordingly, when Ernie Hemingway spent the summer of 1920 recuperating in town, he would have drank Capone’s liquor at the City Park Grill. They served in the basement, and the tunnels that led from the speakeasy to the now-vanished adjacent Cushman Hotel still exist.

But I digress. Capone knew better than to mess with Detroit, and that is why he cut a deal with the Purples (AKA Sugar House Gang) to leave them alone in Whiskeytown.

The four Bernstein brothers, Abe, N-word Joe, Raymond, and Isadore (Izzy) were the punks who terrorized the Hastings Street neighborhood (near what is now the junction of the Chrysler and Ford Freeways). They soon became the recognized leaders of the mob. Having graduated from petty crime to the Big Leagues with the arrival of the Volstead Act. They abandoned petty street crime in favor of to armed robbery, hijacking, extortion, and other strong -arm work. They were notorious for their high profile operations and savagery in dealing with rivals.

The Purples were mentored by two made-men on the Whiskeytown Goodfellas network: Charles Leiter and Henry Shorr. They operated a front business to cover their illegal activities, a legitimate corn sugar outlet on Oakland Avenue known as the “Oakland Sugar House.”

The Sugar House Gang was an early incarnation of the Purples, but was never a tightly-organized organization like Capone’s. They had an interesting wrinkle in their business case. They did not like the heavy lifting that went along with smuggling whiskey. They preferred to hijack other people’s shipments as they arrived, thus avoiding the inherent overhead costs of actually purchasing the liquor in Windsor.

In the Purple business case, it was all pure profit.

Anyone landing liquor along the Detroit waterfront had to be armed and prepared to fight to the death to keep their shipments. As turf was staked out and defended in the early ‘20s, the Purple Gang preyed exclusively on other underworld operators, insulating them from direct contact with the Revenuers and police.

They became infamous when they killed a corrupt Detroit beat cop named Vivian Welch on the East Side. He had decided to augment his $10 a week city paycheck by shaking down speakeasies on his patrol, and the Purples put nine rounds into him after dumping him from Abe Burnstein’s Chevy.

The case is still officially unsolved 84 years later.

The Purples were the undisputed power in Whiskeytown from that murder in 1927 through 1932. During the time, they conducted the Miraflores Apartment Massacre (1927, first use of Tommy guns in a Whiskeytown killing), ran the Cleaners and Dyers War (1928), provided the out-of town muscle for Capone’s St. Valentine’s Day massacre in Chicago (1929) and eventually the Collingwood Manor Massacre (1931).

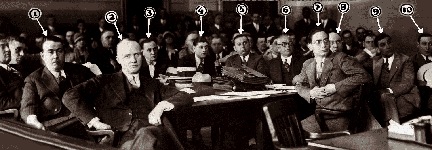

(In September 1928, Purple Gang defendants were found not guilty of extortion in the “cleaners and dyers war.” This photo shows the prosecutors, defense lawyers and defendants during the trial before Judge Charles Bowles. Photo Detroit News.)

The gang had always skated on the charges brought against them, but they were getting greedy and lacked discipline. At Collingwood Manor, they turned on themselves, killing three, and someone who knew too much turned state’s evidence and the leadership went down for Murder One.

That was essentially the end for the Purples, and with the end of Prohibition and the Noble Experiment in 1934, the torrent of whiskey dried up. The successor mobsters branched out into extortion and payday loansharking and gambling that would be the mainstays of the industry through the 1960s.

The quarter of the population who had made their living in the rumrunning business had to get legitimate jobs in the auto plants, and Whiskeytown went back to building cars.

The Purples had a place in Grabbingham. We were way out in the country then, and the place that was rumored to be the hide-out was off Kensington Road, near Big Beaver, but accessible to Woodward Avenue and pre-freeway rapid transit out of the city. We always wondered what went on in the old house, but the last time I looked, it was gone too, like the rest of the city.

(The “Collingwood Manor Massacre”took the lives of Hymie Paul, Isadore Sutker and Joe Lebowitz. This illustration from the old Detroit Times shows how the bodies were found in the apartment.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

The Color Purple

(Members of a local Detroit social group, circa 1930. Detroit News photo.)

It is Easter, the morning of the Risen Christ, and worth a contemplation of color. Nothing is black and white in the Easter season, though our crazy binary natures try to paint everything as either one of the other.

In nature, things are not just shades of gray, but tinged with a thousand shades of brilliant color. In the sanctuaries of the believers around town, the purple of Lent to the black of Good Friday provided graphic visual symbols for the Lenten journey of denial to the bounty of the Easter brunch or dinner.

The change of colors for Easter and the following Sundays helps communicate the movement of sacred time as well as personal faith journeys.

The Sanctuary colors for Easter Sunday are white and gold, the colors of sacred days throughout the church year. For the Easter season, white symbolizes the hope of the resurrection, as well as the purity and newness that comes from victory over sin and death. For those who believe, the gold symbolizes the light of the world brought by the risen Christ that enlightens the world, as well as the exaltation of Jesus as Lord and King.

I am a secular sort of man, one of those reviled Humanists and a recovering Unitarian. It is inconceivable that the Unitarians would have a gang, but even we had our colors at Easter time. The real gangs have theirs, and use them all the year round.

It is part of the fabric of the city now even in those big swathes were there are no longer any houses. I had a co-worker who visited the city recently, and she complained her cheap ass company would only spring for one car for the four who had to travel.

(Herman Gardens Apartments in concept, 1930.)

One of the locals had to ferry her back to the motel in Southfield. Driving on Tireman toward the Southfield Freeway, just on the north edge of Dearborn, they passed what used to be the Herman Gardens housing project. Her driver gave a running commentary on the turf:

“Here you need to put your cap on backwards,” and “here you need to wear red”…”Now you have to put your cap back to the front in this area.”

The Gardens is a microcosm of what happened to the outer neighborhoods in the City. Auto visionary and Shaman John DeLorean grew up there when it was a genteel area; it hit the skids with the diaspora in the 1970s, and things got really bad in the 1980s with the crack epidemic.

The “Young Boys Inc.,” or YBI tried to take over the drug trade in the development and by the mid-1990s the Detroit Housing Commission was applying for Federal money not to fix the place up, but to complete the demolition of more than two thousand apartments.

(Herman gardens prior to demolition. There is planned re-development, in progress for a decade.)

When I was younger and lived in the city, besides the YBI, the gangs included the Latin Counts, Cashflow Po$$e, Darkside and the ubiquitous local chapters of the West Coast franchise organizations Crips and Bloods. I don’t know the colors of the first five, never got close enough to know, but the latter two are proud of the Blue bandanas and Red hoodies.

They are all composed of losers, or those doomed to find associations of the damned in self-defense from their environment, but that is nothing new in Detroit. In fact, the first gang with colors was not made up of people of color, but by poor Jewish immigrants to the burgeoning industrial leviathan.

They chose their color, or rather, had it chosen for them. The story goes that two Hastings Street shopkeepers in the era before World War One were complaining of the punks who were despoiling the neighborhood, hanging out, smoking cigarettes, shoplifting and committing acts of vandalism.

Both of the men’s shops had been the targets of the punks. After one particularly egregious example, One day in disgust one of the shopkeepers exclaimed, “These boys are not like other children of their age, they’re tainted, off color.”

“Yes,” replied the other. “They’re rotten, purple like the color of bad meat; they’re a Purple Gang.”

They ruled the city when it was a rip-roaring and fully functional city when money and liquor flowed like the River through the Windsor-Detroit Funnel, and fully a quarter of everyone working in the city was supporting the bootleggers.

More on that tomorrow. Happy Easter!

(The old Riverside Lunch, home to many a fine sandwich for the bootlegging crowd.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

The Detroit Experiment

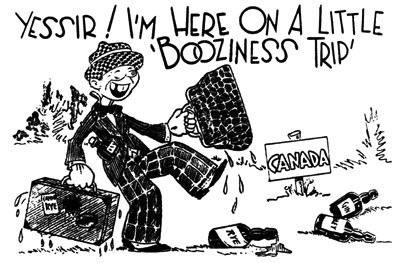

(Postcards that went into circulation in Ontario and Michigan depicting Canada as the barroom for the United States were vehemently opposed by temperance organizations. Cartoon from “The Rum Runners, a prohibition scrapbook” by C.H. (Marty) Gervais.)

Go down to the river, brother, and the throw yourself on the current. It will set you free.

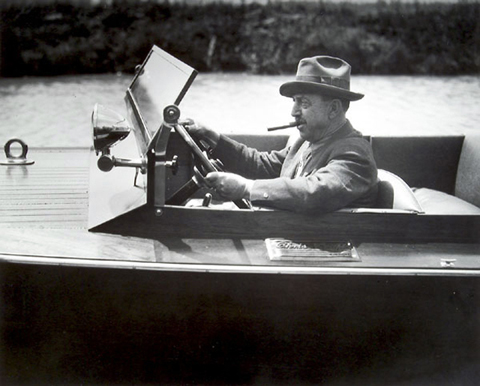

Hear the distant whine of a high-performance marine engine. The Gold Cup races were one of the hallmarks of the summer season on the river, the supercharged engines of the sleek hydroplanes shot rooster tales high in the air. The Cup is actually the first trophy in American motor sports: first awarded in 1904, it predates the famed Indianapolis 500 by seven years.

Hydroplane racing became a tradition in Detroit when designer Christopher Columbus Smith built a Detroit-based boat that would crack the 60 miles-per-hour speed barrier, capturing the Gold Cup in 1915. If the Chris-Craft brand name became a little stodgy in in its later days, it started out with a snarl.

Rupert Murdoch bought what was left of the brand in 2000, and Chris-Craft is as gone from the Detroit riverfront as the Packard is from Woodward Avenue.

(Legendary Detroit boat builder Christopher Columbus Smith.)

The international border with Canada runs right down the middle of the river. If you check the map, you can see there are four points of official pavement crossing on the Michigan-Canadian border: way up north at the Soo, at Sarnia’s Blue Water Bridge just to the north of Lake Saint Clare, and the Ambassador Bridge and Windsor Tunnel right in the downtown Motor City.

But that is nonsense, of course, a perception of the Auto Age. The Lakes and the waterways that connect them were the first highways to the vast interior of the continent, and the water connects it all, intimate and personal.

Hydroplane racing was as much a part of growing up in Detroit as anything and crowds thronged the water to see the boats roar for more than a century. It was the great motor revolution that would transform the world, on land and sea and in the air above. The city was sprouting, too, the iconic buildings that remain, both alive and the husks left behind, were built in the great paroxysm of building that made New York, Chicago and Detroit the hubs of activity in the Jazz Age.

Detroit had something on the other two cities, though of course they lived and Detroit died. It was something that was called The Detroit Experiment, and it was about changing the Constitutions, and in the end it has everything to do with boats and motorcars.

I am not going to bog you down with the history of rock and roll on the Temperance Movement. In the decades after the Civil War, the Saloon was an institution that was central to the live of all American cities and towns. Public drunkenness was a civil bane, and the urge to modify the behavior of the drunks was powerful.

The movement to shut down liquor sales was much stronger in Michigan than it was across the river in Ontario. I think it was because the Canadians could not imagine giving up their cold Labatt’s beer.

World War One enabled the Wilson Administration to achieve social goals in tandem with the war effort, just like the current administration. On December 1, 1918 under authority of the Food Control Bill, President Wilson prohibited the use of barley for brewing.

Michigan had been at its progressive best though, beating the President by a year. The Damon Act went into effect in the state in 1917, and the sale of intoxicating beverages became illegal. The long shadow of Henry Ford was part of the passage. Henry was an intrusive patron. He may have paid his workers the princely sum of $5 a day, but he also expected his workers to live where he told them. Ford even set up a division at Ford to visit workers’ homes to ensure they did not drink or engage in other activities he thought improper.

He wasn’t wrong, of course, in connecting the productivity of his work fore with how drunk they were (remember the legend of Monday and Friday cars) but his serene confidence that it was his right to intrude is still a little breathtaking. Ford’s fierce support of the Michigan Anti-Saloon League was one of the key factors in passing the Damon Act.

Though it was declared unconstitutional in 1919 by the state supreme court, the national Volstead Act became law the same year, and the party was over. At least for a moment.

Despite the vigorous campaign supporting prohibition, Ford continued to serve cocktails at Fair Lane in Dearborn, at least until the national law went into effect. Ambivalence and outright opposition to the law was most common by the very workingmen who were intended to enforce it.

Everyone from police officers and line workers to politicians and judges were involved in bootlegging. It has been claimed that up to 75% of all illegal booze that entered the United States passed through Detroit. To support this large volume of trade, 50,000 Detroit area people were actively involved in the trade- nearly one in four working people.

Most Canadian provinces went dry at the same time the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect. The Liquor Control Act in Ontario (LCA) made public or hotel drinking illegal, but specifically did not prohibit the distillation of hard liquor or the brewing of strong Canadian ale and lager.

For border cities like Windsor, this loophole in the Volstead Act fueled the Roaring Twenties, the decade that defined what the Motor City would look like at its zenith. Just across the river was broad-shouldered and thirsty Detroit, separated only a little water. It didn’t take long for enterprising businessmen in Windsor to set up export docks to supply those thirsty Americans.

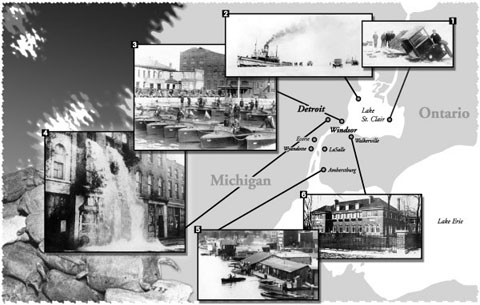

(From top right, counter-clockwise: 1. This beer-laden smuggler’s truck was too heavy for the Lake St. Clair ice.1933 (Detroit News); 2. Jalopies were used to pick up contraband Canadian liquor from vessels in Lake St. Clair (Great Lakes Museum); 3. Detroit Police at river patrol headquarters, foot of Riopelle St.1932 (Detroit News); 4. A waterfall of booze pours through windows of a still on Gratiot Ave (Detroit News); 5. Rum runner leaving export dock at Amherstburg (Rum Running & The Roaring Twenties, Philip P. Mason); 6. Rum runner Jim Cooper’s Walkerville mansion. Also pictured at bottom left are cases of liquor packed in jute bags so they would sink when thrown overboard.)

The Detroit River was a smugglers’ paradise; 28 miles long and less than a mile across in some areas, with thousands of coves and hiding places along its shore and islands. Along with Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair and the St. Clair River, these waterways carried the booze to a grateful nation.

There were no bridges connecting Canada and the United States until the Ambassador Bridge was completed in 1929 and the Tunnel opened in 1930 with the turning of a golden switch by President Herbert Hoover in the White House in Washington.

Since ferry services were inoperable during the winter months (of which I recall growing up there were at least six or seven) the smugglers traveled across the frozen Detroit River by car to Canada and back with trunk loads of alcohol. The route was known as the “Detroit-Windsor Funnel,” a play on the name of the engineering marvel of the Tunnel under construction.

There were barges sunk below the waterline and towed across underwater, filled completely with whiskey. One was found a few years ago, still filled with vintage Scotch. Parts of the cars that went through the ice can still be seen on the river bottom.

Michigan, and Detroit specifically, became a test site for national prohibition. Thus began a steady stream of vehicles to the Ohio border. This served as a trial run for the multitude of citizens who would soon be running rum (and other alcoholic beverages) across the waters from Ontario.

By the late 1920s the federal government was expending 27% of its enforcement budget in Michigan. All that booze, and all that money made Detroit one of the capitals of small-scale entrepreneurial smuggling, and that made the small-fry the target of one of the most savage gangs of the age.

We will have to get to the Purple Gang tomorrow, though. I am feeling a little thirsty.

(Rumrunners crossing the frozen Detroit River. Might have been May or June! Hah!)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Rabbit Ears

(Raven’s Rail Car. A concept design from the American Motors design studio, circa 1955. Photo Socotra.)

Whammo!

The Hubrismobile became possessed by Germanic demons immediately upon impact. I don’t know what it was- a trench or really significant pothole of some sort on North George Mason that I could not see in the darkness. I should never have tried to visit the framing shop after Willow.

It was a hard slam to the undercarriage, significant enough that I cursed loudly and instinctively. The fine German-engineered machine immediately decided to dial “SOS” and the dash display showed the vehicle trying to do the right thing.

The engine still ran, so I punched the menu paddles on the left and right sides of wheel to try to forestall a 911 call that would get me in trouble with the authorities. After several frantic tries on all available menu options, I got the car to calm down and cease dialing, but the poor thing clearly was freaked out.

The status board told me that I had one malfunction, but for the life of me I could not determine what it might be. Both car and driver settled back into routine operations as we passed the office, heading south, and I was relieved that there did not appear to be any significant damage.

I wheeled into the garage under Big Pink and backed into my slot past the elevator bay. Looking into the rear-view, there was a curious curtailment of my field of view. Engine idling, I tugged on the flipper to raise the top, and the car told me to take it to the shop. I looked at the display blankly, and then in the rear view, and saw what the problem was.

The impact had caused the adjustable head-rests on the rear passenger seats to elevate to their maximum extent, or beyond. They appeared to give the rear seats the look of rabbit ears behind me, certainly appropriate for Easter Weekend, but troubling from the perspective of being able to put the top up.

Damn.

I toggled the lever again, in the hopes I could convince the rabbit ears to retract, but the panic reaction of the finely engineered machine was intractable, and it looked like I was going to spend the weekend with the top down.

Jiggs had called while I was out- I missed it, since the phone was in my pocket, and with the top down there was enough wind noise that I didn’t hear it.

I called him back- it was a kind invitation to participate killing or eating a lamb, I think, in celebration of the Risen Christ, but he made a point of saying that he was thoroughly done with stories about Detroit.

“Get over it,” he growled. “That town died fifty years ago and it is not coming back.”

“Yeah,” I responded, looking in my other phone contact list for a number to contact the very professional German engineers who, at vast expense, will cause the ears to minimize themselves.

I over-carred myself on the machine. Damn car has been off warranty for more than a year, and it still has less than 35,000 miles on the odometer. “But there are a lot of stories we have not covered. It was a great town. I haven’t talked about the underwater barges that smuggled real Canadian whiskey under the Detroit River during Prohibition. Or the Purple Gang hideout in Grabbingham, or the crazy concept cars that the Big Three used to put out every year.”

“Nobody cares, Vic. Done deal, it’s over. Be here around five on Sunday for the leg of lamb.”

Jiggs clicked off the connection and pulled out some chicken soup to heat up to fill up the corners of my stomach that the Pollyfarm Deviled eggs at Willow had not got to.

The table was littered with files; real life stories of an epic rocket through the greatness of the American Century to despair.

How could I give up? There was the story about Monica Conyers, wife of Representative John Conyers, (D-14-MI), who modestly advertises himself as a “strong advocate for the disenfranchised and a powerful proponent of justice for all.”

Monica began her service to the city as an activist and community organizer, and later as a member of the City Council. She is not there at the moment, having been convicted of taking $6,000 in bribes in exchange for a vote on a city sludge-hauling contract.

She wants a do-over, despite her guilty plea, but it is not going to happen. She got 37 months in the slammer, which if you do the math, makes honesty seem like a much more economical policy.

(Altar Road Sign. It is going to be a busy Good Friday in Dearborn.)

That idiot Pastor Terry Jones is in court, as well, looking to have a permit approved for his two-person demonstration in front of the Islamic Center in Dearborn.

I wanted to tell you about the Windsor Tunnel, the only sub-aqueous international border crossing in the world, or at least it was before the Chunnel, and the privately-owned Ambassador Bridge (“May I see your passport, please?) or the resurgence of the downtown and the gritty tough soul of a city that will not quite die.

And maybe I will. It is precisely nine days until our little band of urban explorers arrives in the Motor City. Pastor Ford will be long gone, I hope, Mrs. Conyers will still be in custody, and with any luck at all, I will have the top up on the Hubrismobile.

Should be driving Detroit iron, you know? You can hit the Bluesmobile with a sledgehammer and the car won’t yell at you or get hysterical.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Belt of Iron

(The James Scott Fountain on Belle Isle. Detroit’s RecCen in the background.)

Detroit may be capital of the Rust Belt (sorry, Pittsburgh) but once it had a buckle of iron.

It is said that the legendary maker of the modern world, Henry Ford, met a Yemeni sailor in the early 1900s. The story has been around for generations in the Motor City. Henry was paying $5 a day for work on The Line, and his encounter with the sailor began a serial chain of migration of Yemenis to Detroit that continues to this day.

It is sort of weird. Ford was a noted and virulent anti-Semite, one of the nastier parts of the new world he was inventing, but his incidental association with emigrational patterns of humanity based on the opportunity for a decent wage transformed the Iron Belt of America.

As Detroit’s German and Polish faces were joined by people of color, the narrative of racism and conflict in the city gained strident volume. It was about work, first and foremost, and Ford was not racist, per se, in that narrow aspect of his complex legacy.

I remember asking Raven one time long ago as we drove along the Jeffries Freeway about why the big Continentals and Buicks seemed to have so many African-American drivers. Dad replied laconically that “Ford doesn’t care what color you are, so long as you have enough green.”

That was a play on Henry’s old adage that the buying public could have any color Model T that they wished, so long as it was black. I didn’t know it then, but later incorporated the phlegmatic principle of capitalism into the way we looked at the world from Detroit’s northern suburbs.

The resentment against people of color in Detroit long pre-dated the Great Migration. The first race riot in the city occurred in 1863 when the 24th Michigan Infantry of the famed Iron Brigade was off fighting the Confederates. The disorder was unsettling enough that a permanent Detroit Police Department was founded to maintain public order.

It was the behavior of that particular organization that was blamed for instigating the next great act of public disorder in another war year, 1943.

The War and Money lit the fuze to the grenade that went off on June 22nd. Detroit’s population had swollen like a boil since the war began, growing by 350,000.

The stolid Hunkies and Germans and Polacks must have blinked at the influx of Appalachians to their neighborhoods; most of the new-comers were whites from the hill-country of the near south. That was when Ypsilanti, Ann Arbor’s raffish neighbor became “Ypsi-tucky.” 50,000 of the immigrants were African American, and part of the problem was that there was no place for them to go except the Paradise Valley and Black Bottom neighborhoods, which were bursting at the seams.

The fight broke out at Belle Isle, a little open space connected to Detroit by the McArthur bridge. The flash point was a fight of some sort, either black on white or white on black. It doesn’t matter, except to note that there was enough pent up anger that the riot lasted until FDR dispatched Federal troops and restored order three days later.

The fight started at Belle Isle, the largest island park in the country, and home to the posh Detroit Yacht Club (mostly sailing craft) and Boat Club (mostly stink boats), a Coast Guard station and the James Scott fountain. It is not so posh now, and in the years after the park was both home to the enclaves of the elite and an open space for the poor.

I recall to this day the old racist tune that lingered years after:

“I woke up in the morning,

Gave my wife a smile,

Bought a watermelon,

And I headed for Belle Isle.”

There is more, but it is stupid, offensive and petty, just like life was in the bustling factory city.

(Detroit Boat Club, on Belle Isle, MI, 2005. Photo Alex Duncan.)

Belle Isle is still a nice open space, but the plush Boat Club was abandoned by the social organization in 1996 and the magnificent facility they left behind is now crumbling, though there are some renegade rowers who still use the docks. It was the oldest rowing club in the country, and the renegade rowers claim they continue the tradition that makes them the second oldest in the world.

Anyway, there I go on the black-and-white conflict that was the great narrative of the decline and fall of the Motor City. There was much more going on in the background that was obscured by the brutal suppression of African Americans. It was the rise of something else altogether that came with the call to prayer.

Henry Ford’s chance encounter with the Yemeni Sailor echoed across the oceans and made the Greater Detroit area home to one of the largest, oldest and most diverse Arab American communities in the United States.

The earliest wave of Arab immigration dates from 1890, and was composed of Syrian Lebanese Maronite Christians who settled on the east side, near the Doge Brother’s factory complex that straddled Jefferson Avenue. Legendary architect Albert Kahn designed the public end of the complex. The Kercheval body shop was on the north side of the street, with the Jefferson engine and car assembly plant on the south side. The bodies came across Jefferson in an enclosed overhead conveyer belt.

The town really hummed in those days.

Listening to Henry Ford, an enclave of Yemini Muslims established a beachhead in Highland Park, near the Ford Motor company Model T plant, and Palestinian co-believers arrived shortly before the turbulence of World War I swept over the Ottomon Empire. The Iraqi presence in the Motor City was established long before the current unpleasantness in the Gulf; in the Motor City we call them Chaldeans, since they arrived before the establishment of modern Iraq.

The major wave of Yeminis came after the great Spanish Flu epidemic ravaged the country in 1918-19. The plague, at it’s height, was killing a thousand a week in Michigan alone. Since it took mostly healthy adults, it created gaps in the workforce that the immigrants were happy to fill.

They brought their faith with them, and established the Dearborn Mosque in 1937. It was the second mosque constructed in the United States, and gained fame as a local court validated the right of the congregation to broadcast the call to pray over loudspeakers on the roof over the fervent objections of some neighbors.

The court found the noise was equivalent to the ringing of church bells, and hence constitutionally protected speech.

Which is a long way around the rose bush to the reason why that idiot pastor Terry Ford claims he is going to show up in front of the larger and more magnificent Islamic Center of North America tomorrow, Good Friday.

Terry is famous for first threatening to burn, and then actually igniting a copy of the Quran.

Most of us are fairly well used to the idea that people around the world burn our flag, or imprison people for the crime of owning or distributing copies of the Bible and shrug it off. We have that concept of “protected speech,” even if the rest of the world doesn’t.

But Terry is on to something he can use his constitutional right to do that is really irritating.In late March, Jones put the Quran “on trial” at his 50-member Dove World Outreach Center. With his congregants as jury, the holiest book in Islam was found guilty and sentenced to burn at the stake.

I am not making this up, I swear. When the self-righteous moron released videos of the burning online on YouTube, the images instigated violence against NATO forces in Afghanistan and got some people killed.

Pastor Jones claims that the Islamic Center is behind a drive to impose Sharia law in Detroit, and eventually across America. I don’t know about that, but I do know that the circus on Altar Road in Dearborn tomorrow is going to be entertaining. In addition to the Islamic Center’s call to prayer, there are several Christian churches on the street that will also be having Good Friday services.

The Lebanese paramilitary group Hezbollah has put a bounty on the pastor’s head. They seem like a distant threat, until you realize that Dearborn’s Chief of Police is a guy named Ron Haddad, a Lebanese-American, and that is just part of the face of today’s Detroit.

Get used to it, Terry.

Oh, I forgot to mention it, but although this is very much about the Pastor’s anti-Islamic agenda, it was originally organized by a Port Huron militia group known as the “Order of the Dragon.”

We have not talked about the Michigan Militia movement, and I am not sure I am going to.

But, that is Michigan for you.

(Iranians protest Pastor Terry Jones and his “Burn a Quran Day” in Tehran, Iran on September 17, 2010. UPI/Maryam Rahmanian.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com