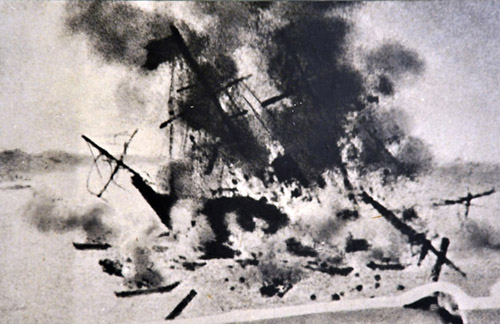

(The SS General Sherman burning. Photo courtesy of the DPRK Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum.)

Elisabeth-with-an-S came by, topped up my Grenacha with a practiced twist of her lithe wrist and kept moving. The belt of extraordinarily intense storms that scoured the South were passing through, and the bar of the Willow had filled up with people who would have been sitting outside, enjoying the warmth.

“Not bad for an attorney,” I said, since she is admitted to the bar in two states, though of course I have been in bars in all of them. She turned and stuck out her tongue and looked questioningly at the Admiral, who put his hand over the top of his mostly-drained Virgin Mary.

“None for me,” he said. “I am good for now.”

“You are always good,” I said. “I can finish this one and be on my way. The Hubrismobile is going to cost $1,200 to have the rabbit ears taken down.”

Mac nodded. “The Jag always costs a thousand when I take it in, no matter what I have done to it.”

We commiserated at the challenge of driving really hot cars for a moment and I regained my train of thought and picked up my pen. “Every administration has to deal with the Koreans, and they all think it is easy, and all of them get taken to the cleaners.”

“Cagey bastards, you are absolutely right.”

“So the latest is that the parts of the DPRK are expected to run out of food in less than two months due to a poor harvest from the savage winter.”

“I would be cautious about reports of dire food shortages in the North,” said Mac. “I suspect the communist state is exaggerating the problem to win assistance from the West, and the Administration hasn’t really internalized how focused those people are. I was the PacFlt N-2 until 1966, after all, and even if Indochina was our primary focus, there was always something going on there.”

“I want to hear about the Damage Assessment on the Pueblo,” I said, “and if the Russians put them up to it to get the KW-7 code machines.”

“I think so,” he said carefully, “but as with everything the North does, there are several layers to consider.”

“I had no idea how far back our history with them went. The Opium Wars with the Chinese are about all that anyone considers about the West in Asia. I knew about the Black Ships and the arrival of the Americans in Japan to open up trade. I didn’t know much about the struggle to open up Korea.”

Mac smiled. “The story of the General Sherman is why Pueblo is where she is right now, and why the Naval Academy had to give back the flag.”

“We never remember our history, but some people do,” Mac declared. “See, the whole thing is about perspective. For those who live in the region, the term “Far East” is a misnomer. It is neither far, nor east. It is the center.”

“That is what I thought when I lived in Seoul,” I said. “I always thought I could hear the whisper of North Korean paratroopers dropping out of the sky. They used those AN-2 Cubs, the fabric-covered biplanes, to deliver special operations forces. The airplanes were too slow and too radar transparent for radars designed to detect hi-performance jets. It was spooky.”

“Always has been,” said Mac. “Just after the Civil War, an ex-Confederate privateer passed once more into private hands. Re-christened the SS General Sherman, she moved on to become a ship of destiny in the Far East, a sort of sister ship to Pueblo.”

“I think I recall some of that,” I replied. “The West was eager to open up Asia to trade. Commodore Matthew Perry had pioneered the concept of forced entry when he sailed up the Tokyo-wan and anchored his Black Ship squadron off the Imperial capital of Edo on July 8, 1853. The cannons were not used in any manner except thinly veiled threat, and resulted in the Treaty of Kanagawa that opened Japan to the world.”

“Well recalled,” said Mac. “They tried the same thing in Busan in the south of Korea the next year, but the Civil War got in the way and no one got back to the idea of opening up Korea until after Appomattox.”

“I imagine the Koreans were a little nervous after the Brits took Shanghai and founded Hon Kong.”

Mac nodded. “The British trading concern of Meadows and Co., based in Tientsin, China, arranged to dispatch General Sherman to Korea to commercially replicate the success of Commodore Perry thirteen years before. She carried a cargo of cotton, tin, and glass. She also mounted guns the Navy had provided, and was intended to offer both promise and peril to the Court of Chosen.”

“So what happened? I gather it did not go very well.”

“No, it didn’t. In August of 1866, General Sherman entered the mouth of the Taedong River on Korea’s west coast, where a representative of the King informed Preston that his country did not trade with the West, and the presence of the General Sherman was unwelcome. The depth of the river would normally have precluded further navigation, but it was swelled with unseasonable rain. At two points he was informed that a decision on trade would have to await the blessing of higher authority. Captain Page thus proceeded onward up the river, past the Crow Rapids to the Keupsa Gate of Pyongyang, where falling water grounded the ship.”

“Not a good place to be,” I said, finishing my wine.

“Very bad. The only accounts of what occurred next come from the archives of the Korean Court. At that time, the Hermit Kingdom was ruled by the Price Regent, the Daewongun. When word came that foreigners were in the river, he sent orders for the ship to depart immediately or all the crew would be killed. General Sherman was stuck, literally. The Koreans believed they had an American Navy ship in their midst, and had little interest in the niceties of its commercial flag. A four-day battle ensued, with the Westerners and their Asian crew giving a good account before they were slaughtered. Records say that two attempted to survive by using smiles and soft words, but they were hacked to pieces with the others who fought, and the bodies were trampled and then burned on the shore.”

“So that is celebrated as a great victory over the Americans by the North Koreans?”

“You got it. Goes back nearly a century before the Korean War, which is the center of their universe and largely forgotten here.”

“Damn,” I said. “That would have been useful to know. And there is the latest crisis. They say the crop yield has fallen by a half and that some people were already eating grass, leaves and tree bark.”

“They say a lot of things,” said Mac, and he signaled to Elisabeth for the check.

(Pueblo Capture Commemorative stamp.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com