(Postcards that went into circulation in Ontario and Michigan depicting Canada as the barroom for the United States were vehemently opposed by temperance organizations. Cartoon from “The Rum Runners, a prohibition scrapbook” by C.H. (Marty) Gervais.)

Go down to the river, brother, and the throw yourself on the current. It will set you free.

Hear the distant whine of a high-performance marine engine. The Gold Cup races were one of the hallmarks of the summer season on the river, the supercharged engines of the sleek hydroplanes shot rooster tales high in the air. The Cup is actually the first trophy in American motor sports: first awarded in 1904, it predates the famed Indianapolis 500 by seven years.

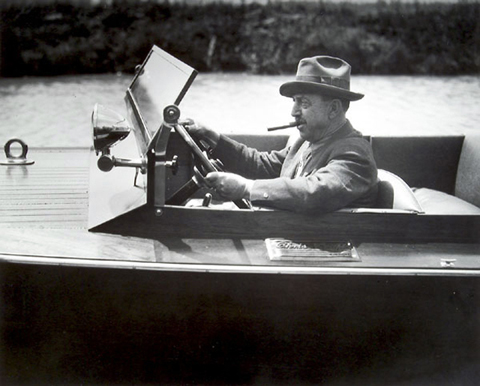

Hydroplane racing became a tradition in Detroit when designer Christopher Columbus Smith built a Detroit-based boat that would crack the 60 miles-per-hour speed barrier, capturing the Gold Cup in 1915. If the Chris-Craft brand name became a little stodgy in in its later days, it started out with a snarl.

Rupert Murdoch bought what was left of the brand in 2000, and Chris-Craft is as gone from the Detroit riverfront as the Packard is from Woodward Avenue.

(Legendary Detroit boat builder Christopher Columbus Smith.)

The international border with Canada runs right down the middle of the river. If you check the map, you can see there are four points of official pavement crossing on the Michigan-Canadian border: way up north at the Soo, at Sarnia’s Blue Water Bridge just to the north of Lake Saint Clare, and the Ambassador Bridge and Windsor Tunnel right in the downtown Motor City.

But that is nonsense, of course, a perception of the Auto Age. The Lakes and the waterways that connect them were the first highways to the vast interior of the continent, and the water connects it all, intimate and personal.

Hydroplane racing was as much a part of growing up in Detroit as anything and crowds thronged the water to see the boats roar for more than a century. It was the great motor revolution that would transform the world, on land and sea and in the air above. The city was sprouting, too, the iconic buildings that remain, both alive and the husks left behind, were built in the great paroxysm of building that made New York, Chicago and Detroit the hubs of activity in the Jazz Age.

Detroit had something on the other two cities, though of course they lived and Detroit died. It was something that was called The Detroit Experiment, and it was about changing the Constitutions, and in the end it has everything to do with boats and motorcars.

I am not going to bog you down with the history of rock and roll on the Temperance Movement. In the decades after the Civil War, the Saloon was an institution that was central to the live of all American cities and towns. Public drunkenness was a civil bane, and the urge to modify the behavior of the drunks was powerful.

The movement to shut down liquor sales was much stronger in Michigan than it was across the river in Ontario. I think it was because the Canadians could not imagine giving up their cold Labatt’s beer.

World War One enabled the Wilson Administration to achieve social goals in tandem with the war effort, just like the current administration. On December 1, 1918 under authority of the Food Control Bill, President Wilson prohibited the use of barley for brewing.

Michigan had been at its progressive best though, beating the President by a year. The Damon Act went into effect in the state in 1917, and the sale of intoxicating beverages became illegal. The long shadow of Henry Ford was part of the passage. Henry was an intrusive patron. He may have paid his workers the princely sum of $5 a day, but he also expected his workers to live where he told them. Ford even set up a division at Ford to visit workers’ homes to ensure they did not drink or engage in other activities he thought improper.

He wasn’t wrong, of course, in connecting the productivity of his work fore with how drunk they were (remember the legend of Monday and Friday cars) but his serene confidence that it was his right to intrude is still a little breathtaking. Ford’s fierce support of the Michigan Anti-Saloon League was one of the key factors in passing the Damon Act.

Though it was declared unconstitutional in 1919 by the state supreme court, the national Volstead Act became law the same year, and the party was over. At least for a moment.

Despite the vigorous campaign supporting prohibition, Ford continued to serve cocktails at Fair Lane in Dearborn, at least until the national law went into effect. Ambivalence and outright opposition to the law was most common by the very workingmen who were intended to enforce it.

Everyone from police officers and line workers to politicians and judges were involved in bootlegging. It has been claimed that up to 75% of all illegal booze that entered the United States passed through Detroit. To support this large volume of trade, 50,000 Detroit area people were actively involved in the trade- nearly one in four working people.

Most Canadian provinces went dry at the same time the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect. The Liquor Control Act in Ontario (LCA) made public or hotel drinking illegal, but specifically did not prohibit the distillation of hard liquor or the brewing of strong Canadian ale and lager.

For border cities like Windsor, this loophole in the Volstead Act fueled the Roaring Twenties, the decade that defined what the Motor City would look like at its zenith. Just across the river was broad-shouldered and thirsty Detroit, separated only a little water. It didn’t take long for enterprising businessmen in Windsor to set up export docks to supply those thirsty Americans.

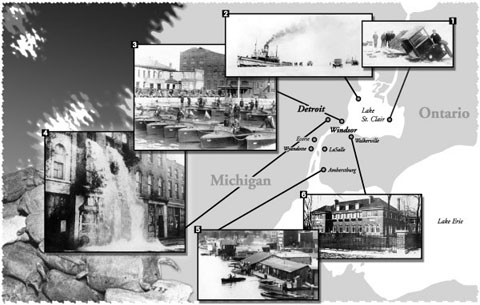

(From top right, counter-clockwise: 1. This beer-laden smuggler’s truck was too heavy for the Lake St. Clair ice.1933 (Detroit News); 2. Jalopies were used to pick up contraband Canadian liquor from vessels in Lake St. Clair (Great Lakes Museum); 3. Detroit Police at river patrol headquarters, foot of Riopelle St.1932 (Detroit News); 4. A waterfall of booze pours through windows of a still on Gratiot Ave (Detroit News); 5. Rum runner leaving export dock at Amherstburg (Rum Running & The Roaring Twenties, Philip P. Mason); 6. Rum runner Jim Cooper’s Walkerville mansion. Also pictured at bottom left are cases of liquor packed in jute bags so they would sink when thrown overboard.)

The Detroit River was a smugglers’ paradise; 28 miles long and less than a mile across in some areas, with thousands of coves and hiding places along its shore and islands. Along with Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair and the St. Clair River, these waterways carried the booze to a grateful nation.

There were no bridges connecting Canada and the United States until the Ambassador Bridge was completed in 1929 and the Tunnel opened in 1930 with the turning of a golden switch by President Herbert Hoover in the White House in Washington.

Since ferry services were inoperable during the winter months (of which I recall growing up there were at least six or seven) the smugglers traveled across the frozen Detroit River by car to Canada and back with trunk loads of alcohol. The route was known as the “Detroit-Windsor Funnel,” a play on the name of the engineering marvel of the Tunnel under construction.

There were barges sunk below the waterline and towed across underwater, filled completely with whiskey. One was found a few years ago, still filled with vintage Scotch. Parts of the cars that went through the ice can still be seen on the river bottom.

Michigan, and Detroit specifically, became a test site for national prohibition. Thus began a steady stream of vehicles to the Ohio border. This served as a trial run for the multitude of citizens who would soon be running rum (and other alcoholic beverages) across the waters from Ontario.

By the late 1920s the federal government was expending 27% of its enforcement budget in Michigan. All that booze, and all that money made Detroit one of the capitals of small-scale entrepreneurial smuggling, and that made the small-fry the target of one of the most savage gangs of the age.

We will have to get to the Purple Gang tomorrow, though. I am feeling a little thirsty.

(Rumrunners crossing the frozen Detroit River. Might have been May or June! Hah!)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com