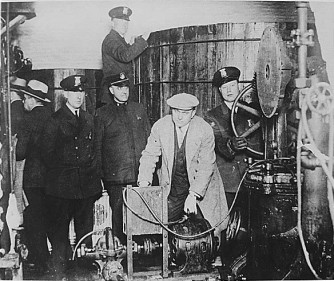

(Detroit’s Finest break up a Whiskeytown liquor operation.)

Elliott Ness, my ass.

It is enough to make a Detroiter spit. That grand-standing son-of-a-bitch was charged with taking down Al Capone, and as head of the 300-man Untouchables, conducted a bunch of high-profile operations against the mobster.

Elliot was never one to hide his brilliance under a bushel basket, and that may be why the Roaring Twenties has a distinctly Chicago feel. Maybe it is a combination of Elliott’s self promoting autobiography and the other grand-standing son-of-a-bitch of the time, J Edgar Hoover, who trumpeted the success of his G-man Melvin Purvis when they gunned down John Dillinger at the Biograph Theater in the Lincoln Park neighborhood.

Chicago got all the great press, and the Tommy Gun is the icon of the age there, but for Pete’s sake, it was Detroit where the booze was flowing and that is where the money was. It was a bonanza, bigger than the automobile industry. Three quarters of all the illicit hooch crossed into the US along the 30-miles stretch of the Detroit River from Lake St. Clair down to Lake Erie.

“Q: Where in Detroit can you buy liquor?”

ANSWER: In open saloons, restaurants, night clubs, bars behind a peephole, dancing academies, drugstores, delicatessens, cigar stores, confectioneries, soda fountains, behind partitions of shoeshine parlors, back rooms of barbershops, from hotel bellhops, from hotel headwaiters, from hotel day clerks, night clerks, in express offices, in motorcycle delivery agencies, paint stores . . .importing firms, tearooms, moving van companies, spaghetti houses, boardinghouses, Republican clubs, Democratic clubs, laundries . .”

In 1918, before prohibition, Detroit had 2,334 liquor serving establishments. During the height of enforcement in 1924, the number had soared to 15,000 establishments that dispensed alcohol. In that year alone, $30 million dollars worth of Canadian liquor was smuggled across the border with an estimated street value in the States of $100 million.

The gangsters in the Motor City- maybe we should call it “Whiskeytown-“ were so tough that Al Capone wisely decided to draw the eastern line of his territory at US-131, the north-south road in west Michigan. It passes through the Little Town By the Bay way up North, and our house there is on the west side of the road, which would have placed us in Capone’s territory.

Accordingly, when Ernie Hemingway spent the summer of 1920 recuperating in town, he would have drank Capone’s liquor at the City Park Grill. They served in the basement, and the tunnels that led from the speakeasy to the now-vanished adjacent Cushman Hotel still exist.

But I digress. Capone knew better than to mess with Detroit, and that is why he cut a deal with the Purples (AKA Sugar House Gang) to leave them alone in Whiskeytown.

The four Bernstein brothers, Abe, N-word Joe, Raymond, and Isadore (Izzy) were the punks who terrorized the Hastings Street neighborhood (near what is now the junction of the Chrysler and Ford Freeways). They soon became the recognized leaders of the mob. Having graduated from petty crime to the Big Leagues with the arrival of the Volstead Act. They abandoned petty street crime in favor of to armed robbery, hijacking, extortion, and other strong -arm work. They were notorious for their high profile operations and savagery in dealing with rivals.

The Purples were mentored by two made-men on the Whiskeytown Goodfellas network: Charles Leiter and Henry Shorr. They operated a front business to cover their illegal activities, a legitimate corn sugar outlet on Oakland Avenue known as the “Oakland Sugar House.”

The Sugar House Gang was an early incarnation of the Purples, but was never a tightly-organized organization like Capone’s. They had an interesting wrinkle in their business case. They did not like the heavy lifting that went along with smuggling whiskey. They preferred to hijack other people’s shipments as they arrived, thus avoiding the inherent overhead costs of actually purchasing the liquor in Windsor.

In the Purple business case, it was all pure profit.

Anyone landing liquor along the Detroit waterfront had to be armed and prepared to fight to the death to keep their shipments. As turf was staked out and defended in the early ‘20s, the Purple Gang preyed exclusively on other underworld operators, insulating them from direct contact with the Revenuers and police.

They became infamous when they killed a corrupt Detroit beat cop named Vivian Welch on the East Side. He had decided to augment his $10 a week city paycheck by shaking down speakeasies on his patrol, and the Purples put nine rounds into him after dumping him from Abe Burnstein’s Chevy.

The case is still officially unsolved 84 years later.

The Purples were the undisputed power in Whiskeytown from that murder in 1927 through 1932. During the time, they conducted the Miraflores Apartment Massacre (1927, first use of Tommy guns in a Whiskeytown killing), ran the Cleaners and Dyers War (1928), provided the out-of town muscle for Capone’s St. Valentine’s Day massacre in Chicago (1929) and eventually the Collingwood Manor Massacre (1931).

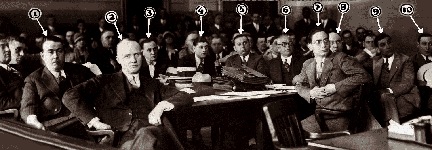

(In September 1928, Purple Gang defendants were found not guilty of extortion in the “cleaners and dyers war.” This photo shows the prosecutors, defense lawyers and defendants during the trial before Judge Charles Bowles. Photo Detroit News.)

The gang had always skated on the charges brought against them, but they were getting greedy and lacked discipline. At Collingwood Manor, they turned on themselves, killing three, and someone who knew too much turned state’s evidence and the leadership went down for Murder One.

That was essentially the end for the Purples, and with the end of Prohibition and the Noble Experiment in 1934, the torrent of whiskey dried up. The successor mobsters branched out into extortion and payday loansharking and gambling that would be the mainstays of the industry through the 1960s.

The quarter of the population who had made their living in the rumrunning business had to get legitimate jobs in the auto plants, and Whiskeytown went back to building cars.

The Purples had a place in Grabbingham. We were way out in the country then, and the place that was rumored to be the hide-out was off Kensington Road, near Big Beaver, but accessible to Woodward Avenue and pre-freeway rapid transit out of the city. We always wondered what went on in the old house, but the last time I looked, it was gone too, like the rest of the city.

(The “Collingwood Manor Massacre”took the lives of Hymie Paul, Isadore Sutker and Joe Lebowitz. This illustration from the old Detroit Times shows how the bodies were found in the apartment.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com