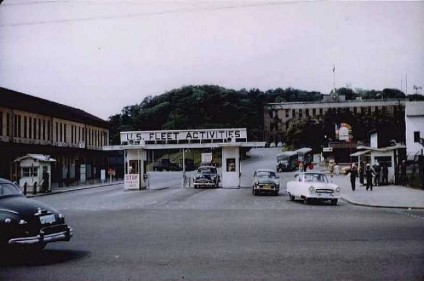

(Main Gate to Fleet Activities Yokosuka, circa 1952.)

I had to pass along the sad news about the passing of Tom “Big Smoke” Duval yesterday, and since there is no good obituary is available, I thought I would let him tell you something about his life and times. With the controversy over the water-boarding scenes in the Hollywood version of real life in the film “Zero Dark Thirty,” Big Smoke’s account of counter-intelligence work in the Occupation of Japan is interesting. I will let Tom tell you the rest, himself.

“Everywhere you turned around there was another hole in security at the sprawling naval complex at Yokosuka, and it was hard to tell where purely criminal activity blended into espionage. That is why it was so important to work with the native Japanese, since getting information out of prisoners is a thorny question.

Maybe I should rephrase that. Getting accurate information is hard.

Even in America, the Police have always had their ways here in America, and the sweat-session and occasional beating is the very essence of the Sam Spade-style detective novel. The problem with that sort of approach is that often the information that is produced is bogus, and manufactured just to get the pain to stop.

The American POWs who were so badly tortured in the prisons of North Vietnam spun incredible tales to try to satisfy their captors. There were interrogation notes that featured diagrams of the live-stock pens, swimming pools and bowling alleys on the aircraft carriers that operated off the coast.

When the truth became known to the Northerners, that their brutal sessions had only produced fantasy, the consequences for the prisoners were dire.

That is one of the surreal aspects about the current controversy over the water board procedure tactic, and whether the CIA should be permitted to utilize it in a small number of cases. It was introduced into the American training syllabus for survival, evasion and resistance school just to give a taste of how bad things could be in the hands of the enemy.

There was a time when the argument would never have occurred to anyone.

When WW II ended, the US Navy ships at the former Imperial Navy Base at Yokosuka off-loaded all the ammunition and stores they could in order to make space for troops to ride the ships back to America in the great demobilization.

There was a lot of stuff to get rid of. Plans for the invasion of the Home Islands, code-named “Operation Olympic,” had called for massive amounts of materiel to be on hand in the Far East for a protracted and bloody struggle.

Every Purple Heart Medal for wounds in action awarded since 1945 comes from the stock that was created just for that campaign. Say what you will about the horror of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the mute evidence of those awards is enough for me.

Meanwhile, I was on my way to clean up the zone of naval occupation south of Yokohama. Corruption was rife, and the Army was threatening to take jurisdiction if the situation was not improved. McArthur’s General Headquarters was not happy.

(Front Gate, Camp Zama circa 1950.)

When I completed my hurry-up orientation with Army CID I caught a train south from Camp Zama to take up my duties, which was to the language and cultural skills of our host nationals to bust up the black market in the Honcho-ku neighborhood outside Yokosuka Base and sever the cords that tied it to things inside the base perimeter.

Yoko is a steamy sultry place in the summer, and a jacket and tie make the shirt cling to the skin. With the economic miracle still a decade away, the skies were still clear, and on many days, the cone of Fujiyama could be seen clearly, south across the gray waters of the Sagami-wan.

On arrival at the police headquarters, I was given a complete brief on the local situation by the Base Shore Patrol and Ration Control office. I was informed of a warehouse that held tons of old K Rations that had been intended to support the troops in the field, and were surplus with the end of hostilities. If I had any use for the stuff, I was told to help myself.

The K-Ration was a creation of the war, and much lighter than the C-ration cans that have been developed before it. The concept came from the Air Corps bail-out emergency food pack, and the prototype was first issued to airborne troops in 1942. The initial response from the field was positive, since the K-rat was light in weight, contained a variety of food products, and fit in the pocket of the M-1943 field jacket.

The Cracker Jack Corporation was awarded the contract, since their famous caramel corn product was exactly the right size, and their experience with waxed paper packaging was the industry standard.

(K-Rats. The ubiquitous P-38 can opener is on the tin to the lower left. Photo US Army.)

All meals contained two packages of dried hardtack biscuits; four cigarettes, gum, sugar and a P-38 can opener to liberate the contents of the small food tins. These included cheese and meat, and powdered beverages. Late production meals included a disposable wooden spoon. By war’s end, millions of K-rations had been produced, but the final assessment was that there were not enough calories in the meals to sustain troops in combat, and the Army had lost the mission requirement for them.

Cracker Jack made the last K-rats in 1945, but like the Purple Heart, they had outstanding shelf life. Some were issued as late as the Vietnam War, and I have no doubt there are still some of them out there in backyard Cold War bomb shelters.

I was a sailor, which means I was always on the look-out for opportunities. I picked up a couple of cases and took them out to my Japanese police squad, where I gave them to the Chief of Detectives to dole out among his officers. The men went wild, opening them up and quickly dining on the exotic contents. It was great, since they offered me their ramen noodles in savory broth in exchange.

My translator gravely told him that the policemen, all combat veterans, were commenting that they now knew why the US troops were so good, since they were so well fed.

At this point, I was not aware that his Chief of Detectives had been a Master Sergeant in Manchuria, and that the whole team had prior seen action in China or the Pacific. Accordingly, the Chief thought they would best be employed on cases relating to corruption in the military, and the hemorrhaging of valuable material from the ship repair facility into the local economy.

One day my assistant came into the office near the gate, saying that the men had requested more K-rations.

Times were still hard on the Kanto Plain, and I looked up, asking if they needed additional food to eat. The Assistant gave me his best inscrutable look through his round dark glasses. He said, tactfully, that the meals were indeed very good, but that the “the biscuits had also proven to be very useful.”

The biscuits were the product of centuries of refinement. They were nearly indestructible on the shelf, and could handle heavy handling with minimal damage. If kept dry, they were nearly eternal.

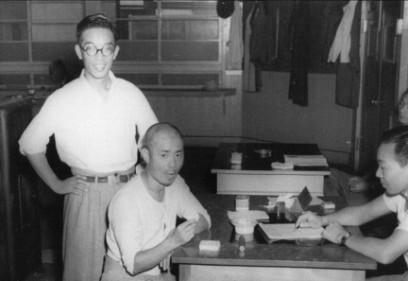

I was curious at that, since the best use I could think of for the things was as paperweights. The Translator took me into the interrogation room and gestured to the current prisoner, who was known to be a hard case, and seemed fanatically determined not to rat out his partners in the Yakuza.

(Members of LCDR Duval’s police squad with suspect, dining on K-Ration crackers.)

The buzz-cut prisoner had missed a few meals prior to starting the questioning session. When I saw him, he had just finished gnawing through a stack of K ration crackers.

Once he had finished his meal, the police team gathered around him, loudly slurping their tea. No one can slurp tea or noodles like the Japanese, a talent I learned at the late night noodle-carts outside the base.

In fact, I always thought it amazing how thirsty a prisoner had to be before they began to talk in exchange for a sip of water.”

This particular subject of interrogation loved the crackers so much that he introduced my police team to all his friends and associates.

I was so impressed by the effect of the biscuits that I wanted to send a thank-you letter to the manufacturer of the K rations, but the wartime contract did not permit the Cracker Jack people to put their customer service address on the box.

My squad was operating under Martial Law rules, and not the provisions of the Army Field Manual on Interrogation.

Today, I suspect that I would not get the medal I received for busting up the black market. In the current environment, I imagine I would be getting a General Courts Martial.”

Tomorrow: Big Smoke in Marseilles

Copyright 2013 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.comRenee Lasche Colorado springs