(Tisquantum, or Squanto, teaching the Pilgrims to grow corn. Public domain image via Wikipedia).

(Tisquantum, or Squanto, teaching the Pilgrims to grow corn. Public domain image via Wikipedia).

I turned on the television after returning from a drink with Old Jim and his bride Mary at Willow last night. It was slow in the bar- the night before a holiday causes Arlington to flush out with the young people going home to celebrate the holiday, though Tracey O’Grady mentioned that she anticipated serving 275 plates of turkey and all the trimmings.

“I am heading down to the farm,” I said. “I am just going to go with something light and local. The eating holidays make me a little crazy,” I said, paying the tab to Brett, the new bartender who looks exactly like the young James Garner from his Maverick days.

At home, the flat-screen contained the usual assortment of nonsense- NBA games and the like- which held not appeal. Scrolling through the lower channels I came across “A Charlie Brown Christmas.”

(Snoopy and Woodstock celebrate the Pilgrim experience. Image Copyright Charles M. Schultz.)

I had not seen it in a while, and despite my now-customary light touch on the holidays, I settled in to watch it.

You may recall the classic animated seasonal tributes from the once mighty Peanuts Empire of Charles M. Schultz. The Christmas and Halloween outings are the most familiar, but this one celebrated Thanksgiving, and despite the hip jazz score, I was astonished at the dialogue of the cartoon characters.

The events of the Mayflower passage were part of the tale, and the privations of weeks at sea, and the great storm that pitched the little ship wildly and cracked a main overhead beam. The voyage damage was severe enough to nearly cause them to turn back. A great screw-rack shored up the damage- and a nice bit of improvised ship’s chandlery in stout V-shaped braces- and the voyage proceeded.

The themes were didactic and manifold, but anchored in stern religious faith, expressed in a way that is completely incorrect these days. And of course the inspirational story of the welcoming Indians.

That is completely out of fashion these days. According to Peanuts, the legendary Squanto was quite the animated stereotype, and his ability to speak English was regarded as a manifestation of Divine Providence. His skills at farming and fishing enabled the little colony to squeak by that first year, and the Pilgrims struggled but adopted his methods and ultimately survived those first desperate winters.

Just as a sidelight, as an adopted Virginian, it has always struck me that the Pilgrim narrative must be associated with the Civil War, and the final solution for the secessionist states. Lincoln declared this fourth Thursday in the November of 1863 a national holiday, at least in those parts of the several states in which his authority held good.

Naturally, the only narrative appropriate to those desperate days was the one of the newly-arriving Pilgrims and their three-day feast in 1821.

Squanto was pivotal to the Peanuts story, and it is well deserved. Squanto- or Tisquantum, in the tongue of his native Patuxent Tribe, is credited with teaching the Pilgrim Fathers and Mothers how to fish, and plant maize, and interact peacefully with the native inhabitants.

Squanto had quite the backstory. He had been kidnapped while hiking back toward Patuxent lands from Jamestown. He was captured by Englishman Thomas Hunt, one of John Smith’s lieutenants, who was planning to sell fish, corn, and captured natives in Malaga, Spain. He reckoned Squanto and his comrades were worth 20 pounds sterling per head.

Squanto escaped, or his enslavement was commuted, and he traveled from Malaga to live in London for a time, learning English along he way. When he had the chance to return west across the water, he took it, landing first in Newfoundland before eventually heading south toward home.

He discovered that in his absence, his whole tribe had perished from a horrible epidemic. It was possibly smallpox, or another contagious disease of European origin for which his people had no natural immunity.

When Mr. Lincoln made Thanksgiving a national holiday, the narrative of the Pilgrims had none of the trappings associated with then-current war between the states. That is the pivot of the modern story, since there are no Virginians in the Pilgrim story, unless you count Squanto.

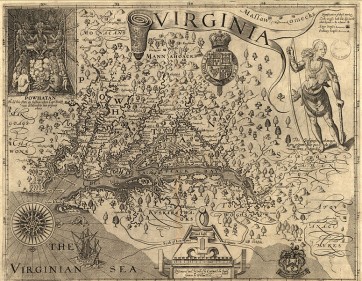

(Map of Virginia, circa 1606, discovered and as described by Captain John Smith, 1606; engraved by William Hole. Source: Library of Congress).

In Virginia proper, Thanksgiving services were being held routinely as early

as 1607, with the first permanent settlement at Jamestown holding a feast of thanksgiving in 1610.

On December 4, 1619, thirty-eight English settlers arrived at the Berkeley Hundred, a tract of some 8,000 acres on the James River, twenty miles upstream from Jamestown. The group’s charter required that the day of arrival be observed yearly as a “day of thanksgiving” to God.

On that first day, Captain John Woodlief presided over held service of thanksgiving. As quoted from the section of the Charter of Berkeley Hundred specifying the thanksgiving service: “We ordaine that the day of our ships arrival at the place assigned for plantacon in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually kept holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

(A 1628 woodcut by Matthaeus Merian shows the March 22, 1622 massacre when Powhatan Indians attacked Jamestown and outlying Virginia settlements. The image is largely considered conjecture, though the deaths were real enough.)

According to the memoirs of John Smith, in 1622, the year after the Pilgrim feast, braves of the Powhaten Confederacy “came unarmed into our houses with deer, turkeys, fish, fruits, and other provisions to sell us”. Suddenly, the Powhatan grabbed any tools or weapons available to them and killed any English settlers who were in sight, including men, women and children.

Chief Opechancanough then led a coordinated series of surprise attacks on the colonists that that killed 347 people, a quarter of the English population of Jamestown, and nine in the Berkeley Hundred.

The forward settlements were abandoned as the colonists withdrew to Jamestown and other more secure points pending arrival of reinforcements.

Later, of course, the colonists would later sweep up the Northern and Middle Necks of Virginia, where so much of our national history was contained for the first two centuries of our national life in the wilderness of North America.

The events that occurred in the Berkeley Hundred have much more in common with the subsequent history of this land than the peaceful dinner up in New England the year before.

Anyway, I was absorbing the quaint message from the Peanuts Gang as I shook my head. That animated version of history is the one I remember from school days long ago. I do not think they learn it that way anymore. But considering that Mr. Lincoln widely recognized that we needed a holiday of Thanksgiving to Almighty God in that bleak year of 1863, and chose another narrative more compatible with the struggles of the North.

No Virginians. So is history made, or the past created anew.

I am glad Snoopy got his version on tape before the Revisionists got their claws into the story to promote the narrative of the moment- which celebrates the stories of those who got run-over in the great race to Manifest Destiny, sea to shining sea.

Have a splendid day and wonderful dinner, and give thanks for how we all got here through the dark forests that bounded the shores of this far and distant side of the storm-tossed Atlantic Ocean.

Thanksgiving indeed.

Copyright 2012 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com