June 18, 1815

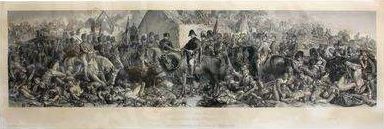

(Detail from the engraved copy of Daniel Maclise’s astonishing fresco “The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher after the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815).

I never know where we will go after priming the pump with a piping hot pot of Dazbog-brand Russian Coffee. I got a fine note about the history of German Armored vehicles in fine-art prints, and that distracted me from the ongoing Climate Wars, the Santorum Campaign, and the stalking murder being clouded by claims of self-defense down in Florida. I allowed myself to vent on the sorry state of politics yesterday, and this morning, found myself taking solice in artistic renderings of monumental events.

I was thinking about the grayness of North Europe, since it is exactly the way my Arlington morning is starting out: pregnant with the prospect of rain, gray as my cashmere sweater, and pensive in no small regard. I was wandering through the archives of the mind- and searched for the war print I like best. I wound up at Waterloo, and with the example of the knock-off fine art I have actually been able to afford.

I certainly could not accommodate the original, since it is huge, and I have few walls these days with the prime real estate already spoken for. The farm was a godsend in that regard for second-tier but much-loved art.

I have a steel etching of this huge fresco, and therein lies a tale. The image leapt out at me in a second-hand store on Woodward Avenue in Suburban Royal Oak, Michigan. I cannot specify the date, except it may have been senior year in college, or about the time of the oil shock, and the price was right around $25 bucks.

I dug down into my elephant-bell low-cut jeans and pulled out my (usually) empty wallet and made a commitment to history.

The print stayed on several of my walls over the next decade, the dry fragile paper that sealed the back coming apart, the nails that kept the long silver-painted rectangle assuming a certain flexibility unintended by the original owner. When I went into the Navy (enlisted, to my surprise, to be an E5 for training purposes prior to commissioning) and lost track of it.

Eventually it migrated with the vast pile of detritus that my folks managed to the crawl space in the Little Village By the Bay where it rested until a couple years ago.

I found it there leaning on the sand floor against the cinderblock wall and tossed the poor thing into the trunk with the cast iron dwarf of whatever car I was driving at the time and brought it back to Arlington. Here I turned it over to Mr. Jimmy, my Kazak framing-and-matting guy who operates KH Fine Art Prints at the corner of Lee and Glebe in North Arlington.

“Jimmie,” I said. “Do what you can. This has been disintegrating long enough. Do what you can to save it.”

He nodded, recommended acid free backing, a couple contrasting mats and archival glass. As usual, the framing cost ten times what the original print had cost.

Jimmie did his usual nice job. In fact, it was impressive. It is now down at the Farm in the room adjacent to the one I took my astonishing fall last weekend. I don’t know precisely how old it is- I might if I was down at the farm and could go look at the spidery script under the title. I think I can reliably date my copy to one of the popular copies of the original work in the 1860s.

The work commenced in 1857, five years after the passing of the Iron Duke.

(I got a copy of this portrait of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS at the gift shop of the Iron Duke’s residence at #1 London. It is in the back bathroom at Big PInk.)

That was the year, 42 summers after the battle that Maclise was commissioned to paint the series of frescoes in St Stephen’s Hall, but changed his mind and began the two monumental wall paintings in the Royal Gallery instead.

(Field Marshall Prince Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, looking fierce.)

Maclise began with a cartoon that became ‘Wellington meeting Blücher’. This was finished with incredible speed and was then exhibited in the Royal Gallery at the Waterloo anniversary in May and June of 1858. The Prince Consort liked it, and was then exhibited in the Royal Academy. The cartoon was then bought by the Royal Academy and is now stored at Burlington House, having been hung for a time in the gymnasium of the Royal Military College at Sandhurst.

Meanwhile, having experimented with fresco in the Royal Gallery, Maclise decided that the commission was too difficult to undertake and resigned. If at first you can’t succeed, quit, right? But after a visit to Germany, he was converted to the waterglass method of painting as a way forward. This method employs a binder of the colors in a soluble alkaline silicate, also called stereochromy, which better resists the consequences of the British damp. The mineral plaster was prepared for him in December 1859 and Maclise began work on the fresco in January 1860, completing the heroic work in the winter of 1861.

In March of 1862 the exhibit was opened to the public, and it was a sensation. I expect the publicity is what prompted the steel etching, so I think my copy dates to some time in the Civil War years here, and naturally was pretty evocative. The exhibition caused a sensation, with visitors ‘marvelling at the fertility of Maclise’s invention’. Critics claimed the composition to be superb, and the details of military uniforms, equipment, the horses and the expressions of the characters exceptional.

Unfortunately, the second commission (‘The Death of Nelson’) did not run so smoothly, and in fact almost killed Maclise. The coincident death of the Prince Consort (and the gloom that settled over Victoria) robbed him of his cheerleader and fundraiser, and by 1864, the war chest was empty.

As Maclise finished the enormous fresco he was described as being ‘worn out with intense application’, and ‘looking like an old, old man,’ precisely the way I have been feeling lately. To a visitor he spoke gloomily: ‘Nobody cares for the pictures after they are done, or wants them, as far as I can see.’

I wanted it, and I spent about $350 to have Jimmie restore and stabilize my copy. I understand modern critics have been charitable to the somber realism of Maclise’s visual narrative. I certainly like it.

The original is something, just over 12 feet high and 46ft 8ins long. The Iron Duke is depicted meeting the Prussian Marshal Blücher at 9.15 pm on 18 June 1815. That will be the day, 97 years later, that my Sister buries Mom and Dad down in Ohio, the day after Bill and Betty’s first inurnment at the family plot in Shippensburg, PA. The Socotras were already living there on the eve of the Civil War, and would be bit-players in America’s most famous battle as the Rebels came to south-central Pennsylvania to encounter the Yankee host in the adjoining village of Gettysburg.

That is the other connection. My great grandfather Socotra, a prim shopkeeper, visited the field at Waterloo on his Grand Tour of Europe in 1903, on May 5th, almost ninety years downstream from Napoleon’s end. He would have been in his late fifties or early sixties at the time of the trip, and the last member of the family to have actually seen the Confederates in Pennsylvania. If he had any specific recollections of the field at Waterloo, he confined them to a postcard, a copy of which survived the dissolution of Mom’s fine library. His words of that day were “We are enjoying the fine sights of the great battlefield. We are all well. W.E.S.”

The strange pyramidal earth structure that dominates the field today is capped by a statue of the British Lion- hence, “Lion Hill.”

In Maclise’s vision, the two heroes of the day are meeting in the ruins of an inn called ‘La Belle Alliance’, which had been Napoleon’s headquarters during the battle. Wellington is mounted on his horse Copenhagen, and immediately beside him (right) are Lord Arthur Hill, General Somerset and the Honorable Henry Percy, with various members of the Life and Horse Guards.

(Blücher (left) is accompanied by Gneisenau, Nostitz, Blülow, and Ziethen.)

On the white horse, with drawn sword at his shoulder, is an Englishman, Sir Hussey Vivian, who was attached to Blücher’s staff. All the details of this historical event were carefully researched. It had indeed been claimed that the two generals met elsewhere in the field of battle, and rode together to the inn.

The matter was settled by not-yet-bereaved Queen Victoria, who wrote to her daughter Victoria in Germany, asking her to question the aged Nostitz, who had been Blücher’s aide-de-camp. He confirmed the details of the meeting. One specific correction was the question of what Blücher had worn on his head. Nostitz insisted that he wore a forage cap instead of the hat and feathers with which Maclise had provided him. The artist made the change.

(Blucher, now with forage cap.)

Maclise painted the picture from 1859 to 1861. With the ‘Death of Nelson’ fresco that faces it across the Royal Gallery, the two works are his masterpiece.

You can see the similarities in composition between the great works, even as the two greatest heroes of the Empire have their unique differences where they lie in St. Pauls. You have been there, I know. Wellington’s tomb is on the main floor, stark and dark. He had a long career after his military triumph. Nelson, of course, died in action and is in the crypt below. His monument is light and crisp, like an enormous bit of Wedgewood china. In these two frescos they are united.

(My print of the Waterloo fresco.)

The prevailing mood is grim and tragic: there is no glorying in a military triumph. In the left foreground a French artillery officer lies dead across his gun, while beside him an English soldier has his leg bound and another is carried off.

On the right foreground, a group of wounded Life Guards, whose officer lies dead against the broken-off wheel of a gun. To the right of the wheel, a wounded officer of the Lancers is tended by a doctor. Further back, a young soldier is carried away. The attention to detail is awesome. You can identify young gallant Howard (celebrated by mad Byron in the poem ‘Childe Harold’) but also that the soldiers bearing him away include a Highlander, an Irish fusilier and an Englishman of the Foot Guard. To the right of this group, a young Flemish officer is given the last rites.

Meanwhile in the background, the routed French flee, pursued by the Prussians, in accordance with a plan agreed between Wellington and Blücher. Pushing on through the night, they drove the French out of seven successive bivouacs, and at length drove them over the River Sambre.

The Campaign was over: the French had lost 40,000 men and almost all their artillery, while the Prussians lost 7000 and Wellington over 15,000 men. So desperate was the fighting that 45,000 killed and wounded lay on an area of about 3 square miles. At one point the 27th Inniskillens were all lying dead, still in their square, and the position of the British infantry I evident from the red line of their dead and wounded.

Anyway, it is always like this, the tumbling down the years. It would only be right to get an etching of the Nelson fresco as a companion, but at some point I think I need to stop acquiring things and start giving them away.

Copyright 2012 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com