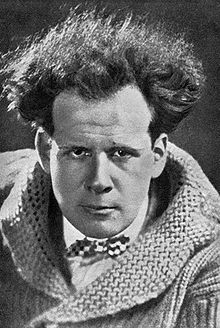

(Soviet film director Sergie Eisenstein.)

My Russian Natasha told me to order a copy of Sergie Eisenstein’s film “October” from NetFlix.

I complied, and it has been sitting on in the pile on the media center for months- maybe since last October, I don’t know. I got energized, though, since I am in a minor war with the video content distribution giant, as you well may be. Better said, they are at war with us. I was surprised to get a note from my friends there- apparently they consider me a friend- saying they were unilaterally changing their business model.

I would consider myself more of a comrade than a friend, having been down the technological rapids with Betamax and Blockbuster, and the painful late charges there, and the midnight drunken rides to get the tape back to the store before incurring late charges, I am sympathetic. It is the essence of capitalism that things change and things are destroyed, like the ubiquitous video chain was eaten alive by the little red envelopes providing DVDs are about to be destroyed by streaming content on the computer.

If I ever solve the riddle of hooking up my spare computer to the television, I will be done with the snail-mail distribution of video content. Or maybe just watch films on the iPad. But in the meantime, NetFlix announced that it was going to start charging for direct download as well as the physical distribution of DVDs by mail.

The new plan, if I stayed with the “two discs out at any given time” and accepted the $8 bucks a month for unlimited streaming would have jumped several dollars. I don’t watch that much content, and never seem to get to the two red envelopes near the flat screen, so I made getting rid of them a priority.

What happened to be there was “The Social Network,” a wonderful and more than a little creepy film about another software program that lives on my computer, and the copy of “October: Ten Days that Shook the World.”

It took me two sessions to complete both, but it was well worth it. The former was about the ruthless application of technology and capitalism, and the latter was an old-school approach to the destruction of the same, filmed as part of the ten-year celebration of the Bolshevik Revolution of October (or November, if you are still using the Gregorian Calendar).

I understand there is an app for that, but I digress.

I have always enjoyed Eisenstein’s. Back in the unsettled days of the 1960s, there were film festivals that celebrated the icons of revolution. Eisenstein’s great film “Battleship Potemkin” was frequently screened, and rightly has been recognized since 1925 as a triumph in the art of cinematic montage, and joyful propaganda. Since it was a silent movie (like “October,”) a simple update to the language of the title cards made the films instantly accessible to any language group.

I fell asleep to images of the righteous proletarians, soldiers, women and sailors in about that order sweeping away the ancient regime, and awoke to the scene-select menu and the endless repetition of the overture. I was determined to get right with Netflix and started the movie again about where I dropped off. It was awesome; a triumph of the will, if I may be permitted an allusion to Leni Riefenstahl’s scary masterpiece of the Munich Partitag of 1934.

She obviously owes a debt to the montage approach pioneered by Sergie, who was exactly the sort of Communist Hollywood was willing to invite to produce films. He had come under fire back home for his creative approach to camera angles and film editing, which were at variance with the increasingly specific doctrines of socialist realism.

Eisenstein got out of Russia, first to Europe, ostensibly to learn more about emerging film technology. In late April 1930, Paramount Pictures offered him a $100,000 to come and make films in Hollywood. In the end, idiosyncratic approach and artistic temperament were incompatible with the way the Studios did business, though he found a sympathetic ear in stars like Charlie Chaplin, and progressives like Upton Sinclair.

The American approach to cinema, in its commercial basis, was as rigid as Socialst Realism and just as hostile to free thinking. Plus, there was a determined anti-communist presence in California and the whole experiment was abandoned by mutual consent.

Eisenstein wound up in Mexico to make a six-film epic for Mary Sinclair and hung out with iconic artist Frida Kahlo and fresco master Diego Rivera, whose work about the ferocious capitalism of the auto industry famously adorns the lobby of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Artistic disputes with the Sinclairs resulted in the loss of miles of negative, and Eisenstein returned to Russia, where he escaped the fate of Boris Shumyatsky, his executive producer at Mosfilms, who was denounced, jailed, tried and shot.

You can almost hear the theme music rising, since after the loss of his Mexican work, failure in Hollywood and disastrous return to the Soviet film industry, he made the critically acclaimed “Alexandre Nevsky.” Stalin was pleased. The script made use of a number of traditional Russian sayings, which was a thinly disguised warning about the growing strength of Nazi Germany.

Sergie was awarded the Order of Lenin and the Stalin Prize, and life was good until the non-aggression pact with Hitler was signed and “Nevsky” was abruptly pulled from theatrical release. Eisenstein was then assigned to do a production of Wagner’s “The Valkyries” at the Bolshoi Theater.

I really enjoyed my visit to the Bolshoi, years ago. The socialist realist art is better than the stuff at the Detroit institute of Art. Oh, and Nevsky was reinstalled on the Russian theater circuit the instant the Nazis crossed the frontier in June of 1941.

The cool thing about command economies is how agile they can be, you know? It was lucky that he came in with a winner at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, since his vision of Communism was at variance with Socialist Realism. Like many Bolsheviks, Eisenstein envisioned a society that would subsidize artists totally, freeing them from the confines of bosses and budgets, leaving them absolutely free to create a pure new art.

Of course, as it turned out, budgets and producers were as significant in the Soviet film industry as it was in Hollywood. Sergei died in 1948 at the age of 50. I saw his grave at Novodevichy Cemetery the same trip we got to the Bolshoi.

Anyway, I am going to have to get rolling. I may get “Battleship Potemkin” from NetFlix, if I remember to add it to my queue. There is something stirring about a rebellion.

Not that there is anything going on downtown that would cause anyone to get upset about government, you know?

(Eisenstein grave in Moscow.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com