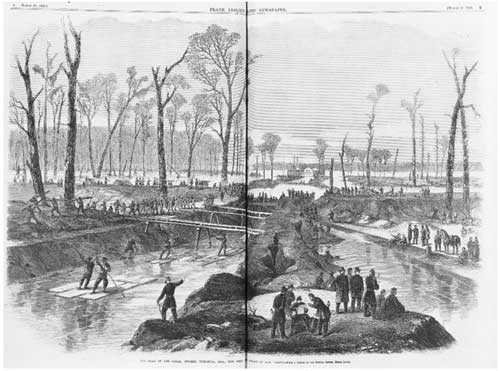

(William’s Canal- later Grant’s- on the De Soto Peninsula near Vicksburg, MS.)

There is little possibility that either Great-Great Uncle Patrick or Great-Great Grandfather James ever saw Major General Earl Van Dorn in the flesh, though they certainly were not far away from one another. In fact, we are coming to a place in the sprawling geography of the civil war in which they were all tantalizingly close to one another.

Van Dorn’s greatest victory might have been at a place that both my relatives knew intimately: Holly Springs. There was a lot going on in the Mississippi Delta country in the winter and spring of 1862-63.

Hell of a legacy, really. Van Dorn was at the bottom of his class at West Point, and had secured an appointment to the Academy because his mother was a niece of Andrew Jackson. He had a successful career in the pre-war Army, and a good showing in the Mexican War and subsequent action against the Empire of the Summer Moon in Texas against the Comanche warriors.

(Colorful Major General Earl Van Dorn in uniform).

Van Dorn got mixed reviews in his conduct as a Confederate officer, though. Dashing and generally successful as a leader of cavalry, he did not appear to have the head to manage large combined forces, or command of logistics. It was the latter that did him in at the Battle of Pea Ridge, in early March of 1862 out in Arkansas when he split his forces and left his baggage train behind in an attempt to get behind the union forces assigned to Brigadier General Samuel R. Curtis.

His men were hungry by the time they arrived in what had been the Union rear, and Curtis had realigned his forces and repulsed the Confederates. That was the beginning of the collapse of the Confederacy west of the Mississippi, but the key to it all was Vicksburg, the last Rebel citadel on the River. Van Dorn was brought back from Arkansas and directed to commence operations to stop Grant’s operations against the last remaining stronghold on the Mississippi. As a field commander, he got whipped at Second Corinth, but in December, he made a daring raid on Grant’s winter Headquarters at Holly Springs, capturing 1,500 Union troops and destroying a Union logistics hub valued a $1.5 million dollars. The raid only delayed Grant a while, who was busy on projects of his own.

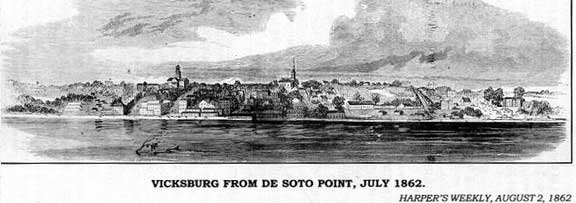

Vicksburg was strategically vital objective for the Spring. Jefferson Davis declared: “Vicksburg is the nail head that holds the South’s two halves together.” President Lincoln knew it, too. During one meeting at the White House, he stated his strategic vision: “…Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

It was the only place where the Confederates still held onto railways running east and west, and it blocked Union transit down the river from North to South. Under control from Richmond, the city blocked Union navigation down the Mississippi; together with control of the mouth of the Red River and Port to the south, it permitted transit with Arkansas and Texas, desperately needed to provide soldiers, horses and cattle.

Vicksburg was known as the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy” because of its natural defenses. The geography was perfect for defense. The Mississippi curled around the De Soto Peninsula on which the city sat, and Rebel guns were positioned to rake any steamships attempting to run by them. North and east of Vicksburg was the Delta of the Mississippi a complex network of interconnected streams and rivers nearly two hundred miles long and fifty miles wide. Even when things dried out in the summer, it was nearly impassible. In the rainy season in which the 72nd OVI waited in Memphis for the offensive to commence, it was literally a quagmire.

And there was the matter of the climate. The winter of 1862-63 was a wet one and all the waterways and bayous were up. The intimidating appearance of the defenses of the inland Gibraltar led to some out-of-the-box thinking. Remember the Bridge to Nowhere up in Alaska?

U.S. Grant had a breathtaking scheme. Why didn’t he just move the Mississippi?

A year earlier, when Union troops made the first attempt to capture Vicksburg, Gen. Thomas Williams began digging a three-mile-long canal across DeSoto Point. He planned on using the canal to bypass the city, but it was never completed. Grant decided to complete the canal and then cut the upstream levee. Engineers assured him that “a wall of water would roar through the ditch and scour out an entirely new channel. Within days the river would shift approximately two miles west of Vicksburg.” If Grant couldn’t capture the city, he would simply make it irrelevant by moving the river.

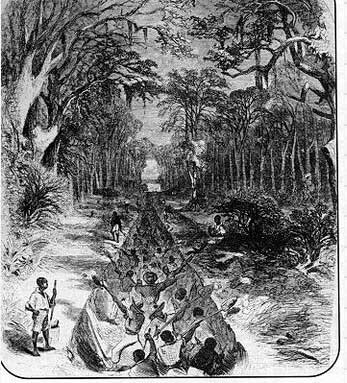

Professor Terry L. Jones of the University of Louisiana put it this way: “Put in charge of connecting the upper end of the canal to the river, Tecumseh Sherman made an inspection and was shocked to find that Williams’s effort was “no bigger than a plantation ditch.” Nonetheless, he began the work with the men of his 15th Corps and an unknown number of slaves confiscated from area plantations.

Continuous rains plagued the workers and caused the flood waters to rise higher. Sherman complained in one letter: “Rain, rain — water above, below and all around. I have been soused under water by my horse falling in a hole and got a good ducking yesterday where a horse could not go. No doubt they are chuckling over our helpless situation in Vicksburg.”

It was a mess. Men sickened in the miasma, and as many as twenty a day died between January and April. were buried in the levee where the corpses often washed out in the pelting rain. Meanwhile, the river was rapidly rising and the swamps disappeared under standing water and transportation on the roads was nearly impossible. I can only imagine the frustration of Grandfather James with his team of horses attempting to travel in the mud. Add the swarms of biting mosquitos and you have a picture of complete misery.

Steam-powered dredges were brought in to help finish the canal, but as Spring of 1863 arrived, the water was coming down, leaving only a foot of water in the canal and barges and boats were left high and dry and abandoned. The press was calling for Grant’s removal.

By late January, Grant concluded that the canal at DeSoto Point would not work. When the flood waters finally receded in the spring, Grant abandoned the canals and marched his army downstream and the Vicksburg Campaign began in earnest.

Grant was roundly criticized for his canal projects, of which the one at De Soto Point was only one of several. The principle was sound, and the climate eventually cooperated to demonstrate that the idea was not crazy. Although the war was long over, the flood of 1876 cut a new channel across the point, not far from the path of Grant’s Canal, and left proud Vicksburg high and dry.

General Earl Van Dorn did not live to see any of it. He was shot in the back of his head by an outraged husband in May of 1863. Not by Yankee troops, but by Dr. James Bodie Peters. He claimed Van Dorn had carried on an affair with his wife, Jessie McKissack Peters. Van Dorn was writing at his desk at his headquarters at Spring Hill when Peters entered the room unannounced and and blew the back of his head off.

It was in May of 1863, when the war in the West was taking a decisive turn imposed by the implacable will of Ulysses Simpson Grant. Van Dorn was the senior Major General in the Confederate Army at the time, and his death cost the service a “useful leader at a critical juncture of the Vicksburg campaign.”

Not that there were not some more interesting events along the way, and the future brothers-in-law in my family were going to be high and dry to see it in person.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303