Editor’s Note: Marlow’s storm memories continue this morning, looking back to an account of a couple 1944 Hurricanes that didn’t cause as much damage as our latest hit from “Ian.” Of course, there were a couple million fewer retirees from Up North living there then, our storm tracking is better now, and fewer people got hurt last week even though there are more of us. So, this is just a reminder of how our predecessors did on this planet with weather that is sometimes- fairly regularly over time- ferocious. If you missed yesterday’s account, it is from his Dad’s recollection from 68 years ago commanding a Navy rescue boat. The damage caused by those old storms was bad enough that news was withheld to prevent public alarm. There was another storm going on, a kinetic one engineered by humans, that raked Europe and the Western Pacific. That was one of the reasons Marlow’s Dad didn’t talk about it. It had been a secret, mentioned in only one single left-hand column on the front page of the New York Times. They had fewer leaks back then. Information leaks, anyway. There was plenty of water.

– Vic

Author’s Note, prelude to Part 2: Navy Crash Boats were flimsy wooden things sporting more than a thousand HP sets of engines that could make them nearly fly out to aircraft crash sites at close to 50 MPH. They couldn’t survive a pier side storm-thrashing, so open cockpit (flying bridge in sailor terms) or not, they were all ordered to storm avoid by going south to the Everglades to ride storms out. So, young Ensign Marlow took his crew. an extra barrel of fuel or two plus lots of strong manila line to sea with him to the skeeter infested marshes to await the coming and passing of not one but likely two storms in the months of September and October 1944. September’s Great Atlantic storm took its time as it lingered for half a day or so before passing by Miami as it strengthened to 500 mile hurricane windfield wide, 160 MPH monster. That said, here is more from ‘now.’

Anecdote #2:

Kilo continued in another email: “I’m glad Mom and Dad are not here to see the devastation. This was the surge that Dad always worried about, particularly in Palmetto Point where their retirement home was. He said it would be deadly and that all of the water from the Gulf and Caloosahatchee River would come over the banks and create widespread, deadly flooding. He worried because Mom didn’t know how to swim. We are just shell shocked. Both of us.”

#3

These and other exchanges prompted me to recall and share something our father related regarding his (previously unrecognized by me) fear of storm surges. He had been a Master of various crash boats (Navy designation AVR or Aircraft Rescue Vessel or later retitled by the more sensitive hearts at the US Navy’s Naval History and Heritage Command as Air Sea Rescue Boat) in southern Florida during WW II.

I had asked from time to time what he saw when he served as a skipper. He was forever wary of talking about those days, likely because he had seen a lot of gore from shark attacks on downed injured crewman that he, his boat, and crew were racing to pluck from the seas and return safely home.

So, I carefully avoided that and related: “When Dad once talked about his WW II crash boat, storm avoidance, anchoring in the Everglades during hurricanes to me a long time ago, he became very still to my eyes and ears as he, perhaps fearfully, recalling how dangerous tending those lines tied across narrow channels to mangroves was as storm surges went up and down.

Those boats had no spare crew, so it was all hands on deck with one crew member rotating down to the engine compartment as Dad manned the open-to-the-elements helm to keep the powered plywood hull pointed in the correct direction to avoid the boat being swamped and the crew drowned . . . .

BTW, even though Mom remained resolutely unschooled in even dog paddle swimming, she made sure all of her chicks learned how to swim all the strokes at Olympic pool.”

——————————

Until these brief electronic sharings, I had never looked into southern Florida’s storm history during the war years. Based on a suggestion from a shipmate and reader of my missives, I did. Lo and behold, Lordie lord, there was such a bad year on both coasts of the southern Florida peninsula — 1944.

That year saw four hurricanes strike or grinded along the US east coast. Back then tropical storms and hurricanes were not formally named as they are now, yet that year the nation’s weather service bureaus monikered two of them, both of which were major storms – a Category 4 one alternatively called the Sanibel Island Hurricane of 1944 along Florida’s southwestern coast and across the peninsula in October and a Category 5 storm called the 1944 Great Atlantic Hurricane along the eastern peninsula coast all the way to New England in mid-September. Since the country was at war, there was little reporting in the press of the day. Due to wartime censorship rules, almost all of what follows came out to the public only well after the war.

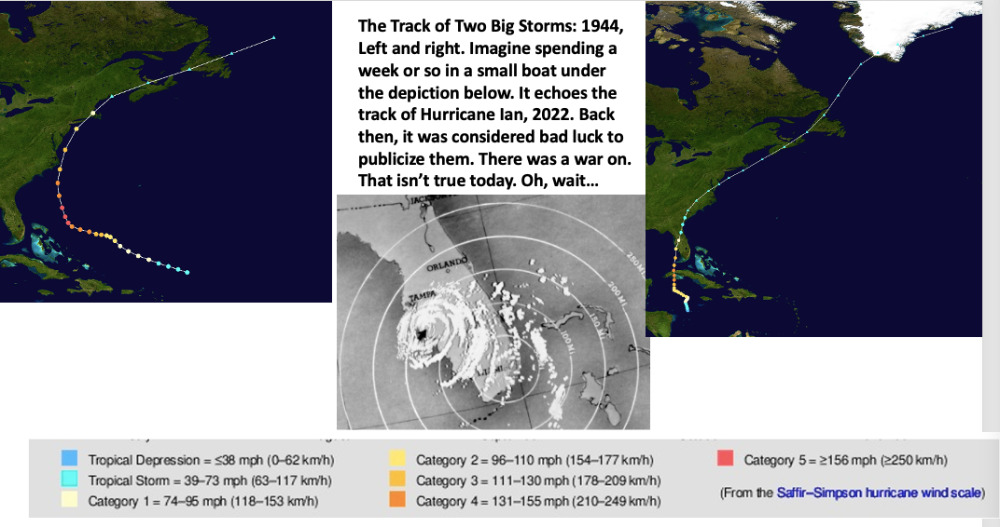

1944 Great Atlantic Hurricane track (left), Sanibel Island Hurricane of 1944 track (right),

color coding of these storms’ wind strength track dot plots (bottom).

Created using WikiProject Tropical cyclones/Tracks. The background images are from NASA. Middle track shows storm width. Tracking data from the National Hurricane Center. Public Domain.

At the time, the United States was embroiled in World War II, and gas and food rationing were still in effect. Yet, local citizens along the eastern US coast were hopeful that the war would soon come to an end and were encouraged by the rebound of summer tourism. Little did they realize that the small disturbance near the Leeward Islands had been growing stronger by the hour, soon to become a major hurricane that would leave large swathes of US east coast in tatters.

The dead count from this first storm was jaw dropping since it was mostly American sailors at sea — 344 — while 46 souls were lost on shore. This storm’s maritime loss records included but were not limited to:

· USS Warrington sunk 450 mi east of Vero Beach, Florida – 248 lost at sea

· Coast Guard cutters USCGC Bedloe (WSC-128) and USCGC Jackson (WSC-142) capsized and sank off Cape Hatteras. Seventy-five men managed to escape onto life rafts from Bedloe and Jackson, but only 32 survived the rough seas and hours of exposure to be rescued two days later.

· 136-foot minesweeper YMS-409 foundered and sank killing all 33 on board

· Lightship Vineyard Sound (LV-73) was sunk with the loss of all 12 crewmen.

So, Ensign Marlow and his crew had to know quite well from local Navy deck-plate scuttlebutt his earlier and soon to occur October crash boat and crew’s storm avoidance orders by late September were quite likely a “you and yours’re expendable” proclamation. Hence, his lifelong aversion to tale-tellings from his WW II service. Even to his seafaring US Navy son.

Nevertheless, as he had in September while offshore of Miami, he followed his storm evasion orders, headed south, and entered that storm’s dragon jaws while working aircrew rescue operations off of southwest Florida coast beaches that distant October of 1944.

1944 Sanibel Island Hurricane damage on its namesake island

The question remains:

“Is there safe storm harbor at night in the Everglades mangroves?”

At the end of the war all of these unnamed crash boats were rotten and infested with borer worms to their cores. Their engines were spent after being used and abused (properly tuned, they could make and hold SOAs of over 50 MPH!) in the tropical climes of both theaters of war. Unnamed you ask? Why sure — the Navy had no reason to properly commission or name them, let alone call these ships “she,” since it spent no money to keep them in paint and powder. These boats, and some salts still say their crews based alone on their boat type’s name Aircraft Rescue, were expendable.

Tough sonsabitches and bastards these wooden hulls and sailors of steel were.

PS: There was one crash boat hull, albeit converted and all dolled up, still in active service of the US Navy as of 2019. It was a four-star admiral’s 63-footer barge in Pearl Harbor. Its primary use in Hawaii was to transport very high-level dignitaries to the USS Arizona Memorial (took #45 and his Melania out to the Memorial in 2017). Originally built for the Navy in 1957 by Knutson Shipbuilding of Halesite, NY, her original U.S. Navy hull number was C-3007.

CINCPACFLT’s 4-star admiral barge

This last-of-her-kind boat’s good luck to have survived all these years ran out in the spring of 2019 when an undetermined-cause electrical fire torched the vessel, leading to its being stricken from the Navy’s rolls and scrapped in 2020.

Hull number C-3037 fire damage

PPS: I have been assured that the following is a “November Sierra” anecdote. A no-shitter:

“At the end of the war, during September and October 1945, the USN surveyed most of the Crash and PT boats and many were deemed to have outlived their useful service life, as recounted earlier above their engines and hulls were in poor condition. Of all the boats surveyed in the Philippines, almost half were considered beyond saving. Since the Navy was more than reluctant to ‘mothball’ wooden boats, later in the fall of 1945, the beached hulls were burned in a series of bonfires that lasted six weeks. About 200 boats of all sizes were burned. Some wise old salts speculate that the group burned on the beach at Samar included a fair number of Navy 63 ft. crash boats.”

PT-124, the “Who Me”ex-“Hogan’s Goat ” was stripped

and destroyed by U.S. Forces 11 November 1945 at Samar, Philippine

Expendable? Sure, but more like reaching for another smoke after the prior one was stubbed out. 1944 had two big ones, and there are plenty of days left in 2022 for another.

Copyright 2022 My Aisle Seat

www.vicsocotra.com