(This is what is left of SW9, and is illustrative of just how hard it would be to find the pesky things if they were just the little stubs. Thankfully, the Daughters of the American Revolution provided the distinctive cage to protect whatever was left, and that is the signature the discerning stone seeker learners to recognize).

I have made a New Year’s Resolution to get this Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia thing done. I am supposed to get with Argo with a plan to venture into the foliage in search of the elusive SE9, the last (actually, second to last- of the District Boundary Stones, first monuments of the new Republic.

Actually, I am going to need a posse, since this will be the third assault on the on SE9, and we have been vanquished twice in both land and river-borne assaults.

I am going to try to not get too far ahead on this thing. It will eventually be a documentary record of how to see them all, were you to be of a mind to do so, and the quest covers all my time living inside the boundaries of what was the complete District of Columbia before the government gave up and decided Arlington was ungovernable and gave it back to Virginia.

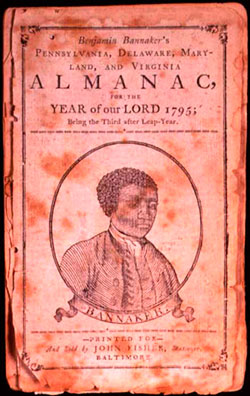

As I mentioned yesterday, the stones were placed at enormous effort by Major Andrew Ellicott and a team of hardy workmen, and located by Benjamin Banneker, a free black man, scientist, surveyor, almanac editor and farmer.

Banneker has passed into legend and is an icon of the Abolition movement. Ellicott was a Quaker and believed firmly in the equality of the races. Banneker had little formal education and was largely an autodidact, something we have in common.

I have written before of this quest to see all the remaining stones. The saga for me began in 2002, when I first learned of the extraordinary and mostly neglected monuments commissioned by Congress as one of the first public works of the new nation.

Major Ellicott’s team placed boundary stones at intervals of one mile all along the edges of the Diamond. It was brutal work, hauling the heavy sandstone pillars to be placed precisely at every mile point along the borders of the new capital territory, with a ten-foot clearing in the dense underbrush on either side. Having trecked most of the distance over today’s version of the terrain, I am here to testify that the brush clearing would have been a massive effort.

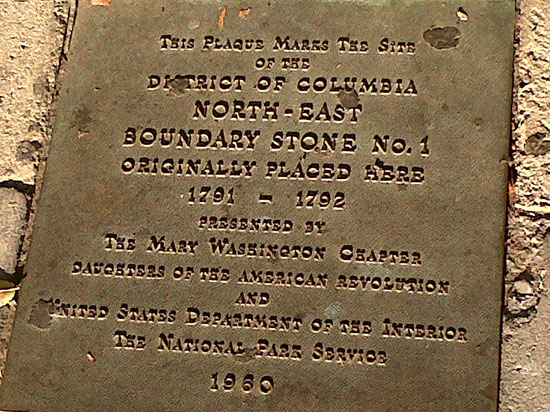

It is a queer thing that so many of them are left, thirty-five to be precise. I guess their survival is a function of representing the edge of things, rather than the middle. Two are in storage after misadventure; one in Alexandria is clearly a copy, though there is no reason for its replacement. Two more are just missing, one replaced with a duplicate, and another trashed and replaced with a plaque.

(This is the plaque just outside the liquor store where NW1 once stood. The original stone disappeared during construction).

They have had their ups and downs over the years. After Ellicott’s team placed them, the next to survey the stones was a fellow named Marcus Baker, who visited each stone’s location during the summer of 1894. Following Baker, Fred E. Woodward photographed thirty-nine of the boundary stones in 1905, all of them except SW2 in Alexandria which is made from the wrong material and is clearly a replacement. Woodward described the extent to which the stones had deteriorated in a series of public presentations and proposed that they be protected for the enjoyment of future generations.

In 1915, the Washington, D.C., chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), citing Woodward’s work, voluntarily assumed the responsibility of protecting the stones by erecting a tall iron fence around each one. For decades afterward, DAR members visited the stones periodically to perform routine maintenance. Despite DAR’s care and attention, however, many of the stones fell on hard times during the mid-1900s. Several were repositioned, removed, lost, or buried during construction projects.

This centennial anniversary of their preservation caused a brief flurry in interest earlier this year, and some refurbishment to cages that had been damaged by cars and other acts of God.

But good times or bad, all of them have locations associated with them, if you care to look.

I have had a pretty good run at seeing them all. My pal Argo has had an interest in my DC Stones adventure, and accompanied me on a chaperoned trip to the Boundary Stone located in the Dalecarlia Reservoir (NW 5), to which (legal) access is controlled by the Army Corps of Engineers. Actually, NW 4 is, too, though you can see it from outside the fence at the Montgomery County line.

Anyway, Argo saw those two with me, since I made an appointment with the Corps after a couple unsuccessful forays into the deep woods outside the Reservoir.

The handful of hard ones was slowly diminishing, since most are fairly near roads or accessible public areas (the ones in private hands in what used to be the District component of Virginia require some modest private trespass).

Left on the menu were SE 8, in the wilds of Anacostia and located in the DC Impound Lot, not far from the unmarked graves of the German U-Boat saboteurs executed in the DC Jail in 1942. That required several trips to identify, and it was useful to have a posse with me, since frankly the place is scarier than shit. Potters Field, Ward 8, deer, drug deals and all that sort of stuff.

DC 9 is the last remaining target. It is on the shore of the Potomac, near what once was the ferry terminus from Alexandria, and now is scrub on the west side of I-270. If you read the literature, you would get the idea that you can simply park your car at the Oxen Hill Park and follow the path, but that is a flat out lie.

There is a path that goes down partly to the river, but after that you are in dense tangled jungle, stumps, logs, trash, and debris fro the period flooding of the vast Potomac. Then there is the barrier of the highway bridge, which is guarded by rip-rap that makes walking hazardous and there is no way to get under the bridge- at least not the way we saw it when we tried, lost in prehistoric wilderness with the 21st century traffic whizzing above is.

Then we rented a kayak to attempt to land from the water but trust me- you do not fully appreciate the power of that great brown river until you are stroking upstream from National Harbor with your butt about twelve inches below the surface. We were defeated a second time.

Next time I am proposing a larger, platoon-sized group with one or two support vehicles to prevent mischance and just drop off the first party at the Jersey barriers on the river side of the Oxen Cove bridge, fight our way through the underbrush, find the stone and document the event.

That will leave NW 8 as the last one to go, though actual touching of all of them once was the goal. That one is located on a trail off Eastern and Kenilworth Ave, and is another I would prefer to visit in a significant sized group to avoid being jumped.

Anyway, if we nail DC 9 that will represent a modest triumph in amateur field archeology. If you an account about some cheery adventurer saying they got to see all the stones in one day, I would offer that it has taken as many as four tries to get at some of them, and the active intervention of the Federal and District governments as well as the Army Corps of Engineers.

This has been a project 13 years in the making and I want to get ‘er done.

(SW8 is in the Patrick Henry Apartment complex. It is worth combining with one of Arlington’s weirder historical locals. Just to the east is a Powhatan Springs Park, former location of the American Nazi Party Barracks. Just to the north of the park is the strip mall where Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell was assassinated by a disaffected follower while visiting the coin laundry. Photo Socotra).

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303