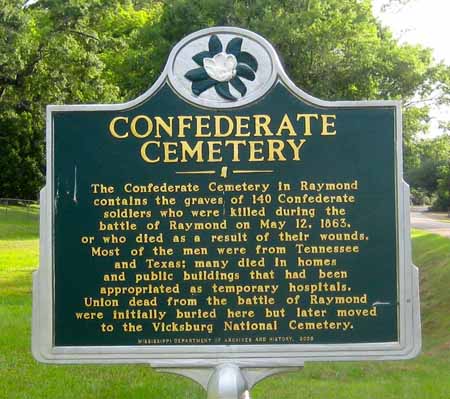

(Those who died during the Battle of Raymond were buried on a hillside in the Raymond Cemetery. The hillside later became the Raymond Confederate Cemetery. Randal McGavock was buried here the day after the battle of Raymond, but later removed. The plot is mowed neatly and well maintained. Photo Socotra).

I felt triumphant that our search had been successful, and what had been family myth was now filled in memory and digital record with a sense of space, and place. The air was moist and gentle on our skin and we turned back on the black-top and drove slowly down to Highway 18 for the right turn north back to Raymond. I took a sheaf of notes out of my back-pack and glanced quickly down Uncle Patrick’s account of the aftermath of the battle, recapping the events that happened after the battle.

“So, Patrick goes back to get Colonel McGavock’s body, which was just where he left it, near the edge of bluff near the sign we found. He got two members of H Company to volunteer to go with him and carry the body. Gregg’s Confederates were beating feet north to escape the Yankees.”

“The ladies of Raymond had made lemonade and a light lunch for them,” said my friend, negotiating off the big bypass road and back onto the human scale of Port Gibson Street. “They could not stop to tarry, and you can say that the Yankees ate their lunch.”

“Uncle Patrick and his comrades were making a slow go of it with the body. They were overcome by the vanguard of the Yankee advance, and Patrick had to threaten his friends at gunpoint to keep them from running. Seeing that capture was inevitable, he let them go. The Union troops gave him the raspberry, but he said he was beyond caring. Eventually the commander of the rear guard, a Captain of Infantry named McGuire, took pity on his fellow Irishman and had the Colonel’s corpse put in a wagon to be hauled to town.”

“Sounds a little like the movie Weekend at Bernies,” smiled my friend, swerving off the road onto the grass near the historical marker at the Raymond Cemetery. We dismounted and walked over to read what was on it.

“A hundred and forty Confederates,” I said. “Where did the Union dead go?”

My friend smiled, a little sadly. ”Look at the terrain, going up slope toward the wrought iron fence around the Confederate graves.” I did, and the lowering sun showed a pattern of shadows revealing oblong dimples under the verdant greensward.

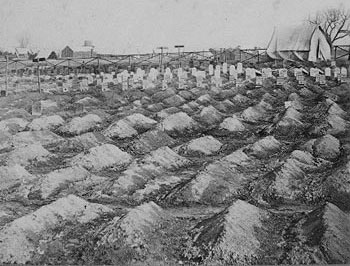

“They were all here, too. There was no provision for a Graves Registration Service in either of the Armies. After the fight, combat troops were detailed to bury the dead before they putrefied. There was no embalming for most of them. There wasn’t any specific provision for it, unless a Suttler following the Army was there to provide the service at private cost. The threat to public health was the biggest deal in what we know now as the first modern mass war.”

(This is what the cemetery at Raymond would have looked like in the days immediately after the battle. This image is of the graveyard at the City Point Hospital near Richmond, VA. Collection of the New York Historical Society, nhnycw/ad ad35012).

“No wonder most of the casualties were from infection or disease. But if the Union dead where here, where did they go?”

“Probably to the National Cemetery in Vicksburg. That is a story in itself. The number of soldiers who died between 1861 and 1865 is estimated to be north of 600,000.”

“Wait, that is more than all the other wars in American history until Vietnam!”

My pal nodded. “Yep, and they were buried where they fell. That lead to a bold plan devised by Army Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs to find, disinter and re-bury the Union dead in a new system of national cemeteries.”

“I knew he directed the first burials at Arlington, partly out of revenge for the death of his son in combat. But I had no idea he was behind an entire campaign to dig up all Union Corpses and bury them together.”

“Aside from the War itself, that was the first big government social program. As Reconstruction was rolled out, resentment was growing across the South. Union cemeteries in the southern towns were becoming an emotional issue. General Meigs dispatched teams to all the major battle sites in a six-year massive Federal program to locate, disinter and rebury the Union dead. Ultimately, well over 300,000 bodies were reinterred in 74 new national cemeteries. They tried their best to identify them, eventually naming more than half. Clara Barton ran her own agency to locate and identify the dead.”

“That boggles the mind, no kidding. Clara’s vision for the Red Cross came out of her experience in Fairfax County and the search for the missing after the war. I saw that her Missing Soldiers Office in DC has become a museum. I will put that on my District Bucket List. Was that only for the Union Dead?”

“Of course. The South was vanquished. Identifying and memorializing the Rebels was a local or State matter, and there was no money for that. Outraged at the official neglect of their dead, white southern civilians, mostly women, mobilized to accomplish what federal resources would not. That is where the cult of the Lost Cause began in the sense of violation. The ladies of Columbus, Mississippi began to decorate the Southern graves in 1866.”

We unlatched the wrought iron gate and walked slowly down the rows of Confederate graves. They are marked with distinctive stones that come to a gentle point, unlike the Union markers that are gently rounded. It is said they were carved that way so that Yankees wouldn’t sit on them.

“And the whole Memorial Day holiday flowed from that, right? But even that is controversial. Some people claim it was freedmen in Charleston who began decorating the graves of Union prisoners in 1865 to commemorate what the fight was really about.”

“Controversial indeed. In fact, like the social changes brought by World War II, there is one America before 1861, and completely different one after 1865. So, your Uncle Patrick brought the Colonel’s body back to Raymond, and then what happened?”

“Patrick was a prisoner, again. By nightfall he had been taken to a hotel in Raymond that was being used as a prison by the Union forces. The Colonel’s body spent the night on the porch. The next morning, Captain McGuire stopped at the Hotel to deliver a two-day parole. Free to move around, Patrick found a carpenter and paid him $20 to build a plain wooden coffin. He then hired a wagon, and a procession of prisoners under guard gave an escort of honor, and the burial was right here. He got the grave marked so the Colonel’s relatives could find it easily. Then he went back to being a POW.”

“He escaped later, right?”

“That is his story, and he stuck to it the rest of his life. His daring escape from a prison boat and the trip back down the river to re-join his family is quite an epic. Ultimately, he rejoined the fight as a headquarters scout and railway saboteur in the Georgia campaign of that crazy Texan John Bell Hood.”

“Good story,” said my friend.

“Might even been true. Patrick named his daughter Louisa McGavock Griffin after the Colonel.”

“What happened to the Colonel’s body after Raymond?”

“My understanding is that McGavock’s sister Ann and her husband, Judge Henry Dickenson, traveled to Raymond and made arrangements for the body to be brought to their home in Columbus, MS. After the war, the remains were moved one final time to Mt. Olivet Cemetery. On St. Patrick’s Day, 1866, Patrick’s Colonel finally came to his final destination and was interred in a formal Masonic ceremony. They say most of Nashville’s Irish population was there to honor their former Mayor. Far as I know, he has remained there since.”

“He moved more in death than a lot of people do in life. Care for a drink?”

I did indeed. We walked back down the hill and mounted up to drive the back roads back into the future, and presently we found ourselves in the bright lights of Clinton.

We stopped at an Applebees near the Holiday Inn Express. It was Mother’s Day, and the crowd was brisk and very diverse. We sat at the counter in the middle of the restaurant and the server brought us some menus.

“Sweet tea?” she asked pleasantly. “Sunday, no liquor.”

She must have assumed we were ignorant Yankees, but was courteous about it. It is the way of things down South.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303