(The very first Nash Healy. It recently went at auction for a cool half million)

OK- we have covered the end of the Big War before and I won’t bore you with it again. Our pal Mac Showers was there, and even was in Japan five days after the surrender. I know what he did- he was the acting Fleet Intelligence Officer when the grown-ups fled the former war-zone to sort out what was going to come next back in Washington.

And as you know, there was a lot. There was a whole economy to transform, millions of people to demobilize from the armed forces, and consumer demand for all the stuff that had been rationed “for the duration.”

Raven was in the third-to-last graduating class in the pilot training pipeline at Naval Air Station Pensacola. In those days, you got your commission as an Ensign the same day they awarded you the Wings of Gold, and along with it came the choice. Most of the early training cadets were just sent home, since there would be no need to invade the Japanese Home Islands.

Sort of an odd thought these days, but drinking with Mac Showers and hearing how the Navy contracted from it’s swollen level was a real eye-opener. Mac elected to stay in and make the Navy a career as an intelligence officer. They offered Dad’s class the option of staying active and going to the Fleet, or accepting a reserve assignment and go home.

Dad decided to go home to New Jersey, attend Pratt Institute’s School of Art and Design, and go into the burgeoning consumer products design field. I don’t know if he was already thinking cars, but his Big Brother designed airplanes, and it would not have been much of a leap.

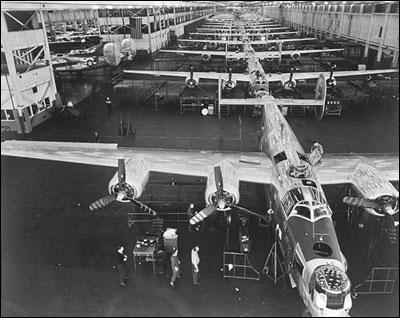

The 1946 Indianapolis 500 Race featured a 1946 Lincoln Continental as the pace car, showcasing Ford’s return to the expensive and exotic passenger car market after building B-24’s at the amazing Willow Run plant that chunked out a heavy bomber every hour, round the clock, in it’s peak production phase.

That is the Arsenal of Democracy at work- and it was a colossus that provided all the capacity to build just about anything in whatever quantities were required.

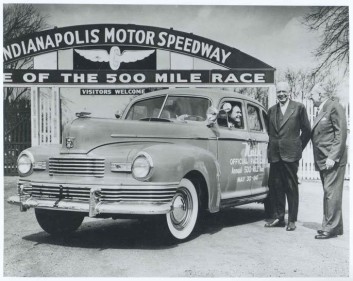

It is interesting to think that the plant capacity funded by the Government’s bonanza of war contracts contributed to the demise of the free-wheeling auto industry- But George Mason at Nash had contributed $37 million in war production to the push to Victory, and when the conflict was done, he was ready to go to the races.

At Indy in 1947 the pace car was a Nash Ambassador, the only time the company would lead the field. A surprising fun fact is that the Ambassador overhead valve six cylinder engine was only 18 horsepower shy of the Lincoln’s massive V-12 engine, (112 horses vs 130 for the Lincoln).

Mason was a man of many parts. Industrialist, of course, but also a photographer and fervent outdoorsman. In 1949, he embarked on a trip to Europe to investigate possibilities in England and Italy for innovative design and engineering. The effects of the war lingered in the UK: the beleaguered Empire was just ending the war-time rationing of clothing. He took the elegant Queen Elizabeth, and therein lies the story of the first purpose-built American sports car of the post-war era. You can tell that to those guys in the Corvette club, too.

Racer and auto builder Donald Healey was returning to the UK after a disappointing series of meetings with Generous Motors execs in Detroit. Healy had a vision that would resonate down through the years of the Giant Engine harnessed to a Little Car. The Cadillac 331 V8 engine featured a “dry” open runner in which coolant exited through an assembly attached directly to the cylinder heads- it required use of a tappet valve cover on intake manifold and a rear-mounted distributor and featured shaft-mounted rockers. It was viewed as the state of the art, and GM sniffed at the idea that Healy would stuff them into an allow-bodied sports car.

Crestfallen, Healy was returning home to consider his options when he met George Mason on the great transatlantic liner. Both men were interested in photography, and as their friendship deepened on the passage, they began to talk of their other passion- fast cars.

They two agreed that motor racing was a necessity in the development and promotion of a sports car, and what’s more, Mason thought his Ambassador engine would be perfect to power such a car.

Healy’s vision was of a sleek lithe, lightweight alloy-body fabricated by the British firm Panelcraft, spare styling and interiors, and speed to burn.

The Nash-Healy designed from the very beginning to after the very best racers in the world. With the engineering genius of England’s master car designer and the backing of Mason’s Nash Motors, it was entirely possible that they could put together a world-beater. As soon as first prototypes were ready, they began to appear on the racetracks of the world ready to take on the very best.

Yes, that little Nash Rambler was ready to stomp on it.

June of 1950: Le Mans, Nash Healy versus Talbot, Ferrari, Jaguar, Aston Martin and Allard. The last of those famous marques is sporting the gigantic 5.4 liter Caddy engine that Donald Healy could not get for himself from GM.

After 24 hours of racing the checkered flag waved wildly as the Nash-Healy roared past in fourth place, behind two Talbots and an Allard, driven by the legendary racer Sidney Allard himself. The brand-spanking new Nash Healey made a huge statement in the biggest racing event of the year.

In celebration, George Mason authorized production for domestic sale of the international car as a halo vehicle for his Rambler and prospective sub-compact Metropolitan.

It worked. In 1951, the Nash Healy placed a respectable sixth at Le Mans. In 1952, the Nash-powered Healy streaked to third behind only two lavishly-funded Mercedes cars.

In addition to its record at Le Mans, the Nash-Healey competed at the famed endurance drive of the Mille Miglia, finishing as high as 30th (out of over 400 entries in 1951) of 173 finishers. Nash-Healeys also competed there in 1952 and 1953.

(This 1953 Nash Healy is dressed to campaign. Image ConceptCars)

You would think that this heritage of racing success would translate direct into sales, but the vast manufacturing capacity of Ford and General Motors prompted a frenzy of cost cutting as Henry the Deuce decided his family-owned company could pass GM as the world’s largest automaker.

The collateral damage to the smaller manufacturers was devastating. In the case of the Nash Healy, shipping costs were a major component of the MSRP. Engines and drivetrains had to be shipped from the plant in Kenosha, Wisconsin, to England for mating with the Panelcraft and Healy-fabricated frames before being put on the ship to return to the US.

The sticker price for the Nash-Healy was a little short of $6,000. Generous Motors put the price point for the new Chevrolet sports car- the Corvette- at fifteen hundred less, an enormous differential in 1953 bucks.

The bean counters had their way with the lightweight alloy bodies. In 1952, alloy was out and cheaper steel was in. The steel bodies were fabricated by Pininfarina in Combiano, Italy, and the headlights were moved from the fenders inboard to comport a family resemblance to the placement on the Rambler Ambassadors.

Longer and wider, the tail finned, beauties were glamorous, but had “road hugging weight.” They could not hold a candle to the Panelcraft alloy cars, which were the ones that competed so well. Only one hundred and four of the alloy Panelcraft production cars were built, and according to the Nash-Healey registry, only twenty are still accounted for and of those, only seven have been restored. as of today 20 are accounted for. Of these 20, seven are in operating condition.

I don’t care. I think the goggle-eyed 1952 and ’53 models are still cool. Price killed them, and the last of the 1953 production models were sold as 1954s, but George Mason’s day at the races was done. He was still convinced that the transatlantic connection could work, if he found the right product.

In 1954, he brought the first of the cute little Metropolitans to sell in America, and Dad got one of the first. I mean, cute as hell, but one thing was for sure: no one was ever going to take one to Le Mans.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303