I follow all the news about Detroit with a sort of grim fascination about what is next for the hapless city. An alert pal sent me a blub from the LA Times about the next disaster:

Detroit is violating the human rights of residents by cutting off their water service because they have not paid their bills…”When there is genuine inability to pay, human rights simply forbids disconnections,” said Catarina de Albuquerque, a Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation at the UN.

The city warned in March that it would being cutting off water service of up to 3000 customers each week because nearly half the accounts in Detroit were delinquent. And this month, the City Council approved an 8.7% water rate increase to help get the municipal utility on a stronger financial footing.

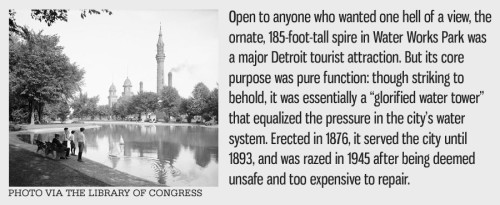

The water works were the gems of the big cities of the Midwest. The one in Chicago is as ornate as the one in Detroit, but even the water is becoming a casualty of the hollowing out of the poor city. Fewer people paying fewer bills causes the price to go up, and like the real estate taxes, it is a death spiral.

I always envied Chicago, as a Detroiter, as “the City that worked.” But of course, it doesn’t either, and for many of the same reasons. Mayor Emanuel is confronting all of the issues that drove down the Motor City and he is not doing a great deal better. The racial component cannot be underestimated.

(Detroit’s water intake on Lake St. Claire. Image courtesy of DetroitYes).

We were talking about it last night at Willow. Boomer the bartender is African-American, daughter of a police officer, and as she says, “we were always middle class.”

She works hard. She lives with her Dad, at his home thirty miles away from the bar, and she marveled at the change in the neighborhood. It had been a majority white population with a few black families. She said she looked around one day and noticed that all the houses had Hispanic extended families living in them.

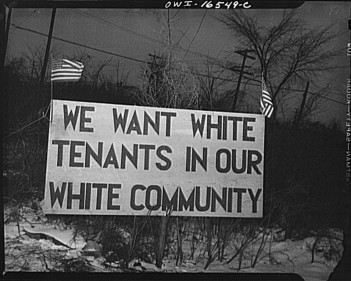

That got us to talking about Detroit’s lack of affordable housing- the burgeoning African American workforce that came north to work in the Arsenal of Democracy had money, but Detroit had no homes for them to buy or rent, and the Red Lining practices of the loan industry was stacked against them as well.

Here is 1943: the war is in full roar. 50,000 African Americans and 300,000 whites (largely from Appalachia, a legacy of which are nicknames like “Ypsa-tucky” for Ypsylanti) have arrived to build bombers and ordnance.

The influx of new residents- of which my family was one a few years later- just about equals those who now remain in the former “Paris of the Midwest.”

Housing in Paradise Valley and Black Bottom, the two main African American neighborhoods, featured many homes without indoor plumbing at twice or triple the rates paid by white citizens. Efforts by Washington to establish new housing for the necessary new workers resulted in racial strife over the selection of the location for the Sojourner Truth housing development at the intersection of Nevada and Fenelon streets.

By the name, it was obvious what the nice people from Washington intended. The white neighborhood was having none of it. This was one of the signs of that time:

(Signs at the prosed site of the Sojournor Truth Housing Development at Nevada and Fenelon in central Detroit, 1943. Photo Detroit News).

At the Packard Plant not far away, three African American workers were selected to work on the line with the Hungarian, German and Polish skilled workers. 25,000 white workers walked off the job.

Later that June the temperatures rose and people began to spend time outdoors, a tradition in the urban areas of the Upper Midwest where the relief from the severe winters is palpable. One popular destination was Belle Isle, a Frederick Law Olmstead-designed park on an islet in the Detroit River. Words between ethnic groups were exchanged. Harsh words. Rumors of outrage swept across the communities- a black woman and child had been thrown in the river went one, and another claimed a white woman had been raped on the Belle Isle Bridge.

The situation escalated and lead to fighting. The riots lasted three days and ended after Mayor Jeffries (now remembered as the Jefferies Freeway across the same neighborhood) and Michigan Governor Harry Kelly asked President Roosevelt to intervene. Federal troops put down the disturbance after three days and 34 deaths. 17- mostly African American as best I can tell- were killed by the Police. Most of the rest of the killings were never solved.

Mom and Dad moved to 14897 Sussex St not far from there in 1950, moving to 14230 Kentucky St in 1952 after I arrived and they fled the city in 1954 as my brother and sister joined the family. “Block Busting” realtors moved African American families into white neighborhoods.

The result was “white flight” which rapidly changed the racial composition of large swathes of the city with great profit to the real estate and financial communities as they met pent up demand. Whites sold low and blacks bought- or rented- high and were often swindled in the process.

The city was starting to change rapidly. The Police knew it and tried to keep a lid on it. The succeeded, for the most part. At least they kept a lid on things until a blunt trauma occurred on a hot night in the late summer of 1967.

But we have talked about the raid on the Blind Pig on 12th Street before. Still, it was the night that the great city on the river began to writhe in mortal agony. And today? Water water everywhere, and not a drop to drink.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303