Sorry-got off on the Cold War this morning with the usual suspects. Maybe it was part of the informal celebration of Soviet Victory Day yesterday at Willow- the one that commemorated the final victory over Nazi Germany by he Red Army.

We started with some thoughts about the Boko Haram, the militants who kidnapped almost three hundred young women for the crime of going to Western-style schools, and the subsequent massacre the group perpetuated against male and female citizens of the remote town of Gamboru Ngala in a remote corner of Northern Nigeria.

The city was essentially unprotected, as Government troops were off looking for the kidnapped girls, and Boko fighters spent 12 hours gunning down civilians (male and female), lobbing home-made bombs into homes and torching shops. Some estimates put the number of murdered citizens as high as three hundred.

That led to a vigorous discussion about why these particular fanatics were not sooner placed on the list of known terrorist organizations, which is curious, but hardly something I wanted to spend the morning exploring. What resonated most powerfully was the discussion about a resurgent Russia and increasingly assertive China. Since we don’t seem to have a plan to deal with either, we got to talking about what we were expected to do in the event of miscalculation back in the bad old days.

One of them was to go underground. McNalley’s Alley was the tunnel to the rear adit of one of the old forts that remained- remain- from the darkest days of the Cold War, before Soviet missile guidance improved to the point that they could reliably hit the known “secret” locations. Most of the hardened structures date to the late 1950s, and a lot of money was spent on them.

There was another program that followed the abandonment of the Forts, but they turned out to not actually have been rendered completely irrelevant. In the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, a few of us were mobilized to hunker down under the concrete and stone behind blast doors of steel.

Just as an important note for the post-attack tourist, there is not a great deal to do down there. Accordingly, we took delight in exploring the place. There were reservoirs, decontamination stations, the hospital and the crematorium, the double blast doors, the office spaces for a variety of agencies, some of them three stories high. All the agencies and offices were expected to have an alternate location and be able to run the affairs of government from there.

The Alley ran to one of four “towers” (two on either side of the front and rear entrances) that ran up to a point near the surface with their own heavy blast doors that were not used, but which would, in the event, provide a means for little bulldozers to venture out to the blasted surface and re-erect communications antennae that would have been vaporized in the Great Exchange.

We wondered what the troops designated to accomplish that would have thought about the radiation exposure. There were a lot of very strange things out there. I still have a yellow box with the famous Civil Defense logo on the side, part of some piece of long obsolescent Geiger counter.

I know why the whole thing remained such a big deal- I saw a picture of the Shah of Iran at the facility where we worked. But the real program had moved on to a mobile system that would not be vulnerable to pre-programmed targeting.

I remember the savage delight some took in physically- kinetically- blowing up the white vans to ensure that the system had a stake through its heart and the agencies no longer had to pay for a capability that was only intended to deal with the stuff of nightmares. Best not to think of it.

That was the early 1990s, of course, when history had ended and peace had broken out all over and pretty flowers bloomed.

Or something.

Anyway, that didn’t quite work out the way we thought it was going to, and after 9/11, I was engaged in the survey of alternate locations still in the Government inventory as places to continue operations in the event of some catastrophe in the National Capital Region. There were a couple of the undisclosed locations that remained in long-term storage; others (Like Site R) that were acknowledged and others that were not. There were others that were mothballed, while some had been sold off.

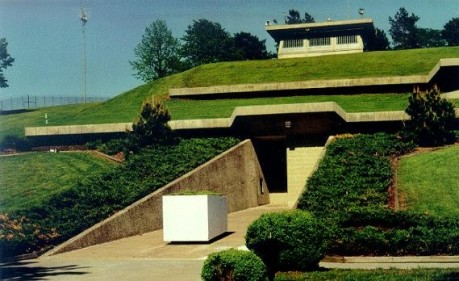

(Mount Pony shortly after decommissioning. It doesn’t look like this any more. Photo Library of Congress).

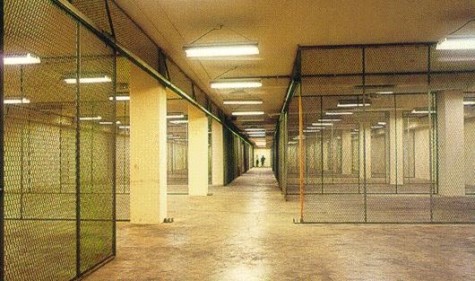

One was the bunker at Mount Pony dedicated to the Federal Reserve’s continued existence- there was rumored to be a stash of small bills on pallets in the range of a few billion dollars – to restart commerce after the nuclear exchange with the Soviets. The money was long gone after the end of the Soviet Missile Threat, though the real estate flyer offering the property for public sale was kind of neat.

(Cages in the Mt. Pony Bunker that once held pallets of small bills. Now they are a home for old Hollywood movies. Photo Library of Congress).

We thought a lot of improbable things back then; with the assessed improvement in Soviet missile technology in the late 1960s and early ’70s, the bunker defense strategy was deemed outmoded. Rather than hunkering down under concrete and earth in a location probably known (and targeted) by the Strategic Rocket Forces, the government would go “road mobile.”

One of the last Cold War survival drills in which I participated involved a long direct flight on a military transport out of Andrews AFB with selected members of the Joint Staff to establish an alternate operating location in a western state. The white vans were all there- and I realized then that you occasionally saw them out in public on the Interstate, just like the trucks that moved nuclear stuff around- and almost always at FEMA disaster sites. They hid them in plain sight.

The J2 asked us in a private moment if we knew that this was the real deal, would we report to be whisked away from our families at the moment of disaster.

I said “probably not.” I suffered no immediate consequences for my honesty.

In 1992, the Washington Post ran a big story about the facility the Greenbrier Hotel that was intended to support the Congress of the United States. I remember the impact of the story: the facility was immediately closed, and the bunker returned to the hotel. There were people itching to harvest the Peace Dividend and the costs of maintaining the bunkers all over jurisdictions adjacent to the Capital were continuing irritants in a time of steeply declining budgets (any relation to the current environment is purely coincidental).

(The Greenbrier now offers tours of the post-attack Congressional Bunker. Photo courtesy The Greenbrier).

The Greenbrier had been in patriotic cahoots with the Government, of course, and a facility large enough to support the Congress in the immediate post-attack environment was significant enough that it was hidden in plain sight, and some of the public spaces were used for hotel functions. You can take a tour for $30 bucks, though you can save the money with the virtual tour at the Civil Defense Museum site. All of us of the “duck-and-cover” generation will feel the old dread come back looking at the images here:

http://www.civildefensemuseum.com/greenbriar/index.html

Mt. Pony was on the commercial real estate market for a while in the mid-1990s, but the Library of Congress wound up using an option to acquire the bunker, where private donations funded the David H. Packer Media Center to restore and preserve old nitrate-based movie films.

I think there is a codicil in the bequest that permitted the acquisition to the effect that the facility can never be used for anything scary like surviving the holocaust.

I always think about it when I drive by on the way to the farm. You can see it from the highway, as you can many of these things. Back in the day, they figured the most effective way to conceal them was to just hide them in plain sight.

That is still true, I think. Look around.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303