Thanks for bearing with me- the tale of The Parental Project in Michigan is painful both in the telling and the listening. I am pleased to be back in my own bed, a place of splendid comfort (albeit solitary) and hanging out with Elizabeth-with-an-S and Old Jim and John-with-an-H at Willow.

One of my confederates reported a sighting of Jim-the-Bartender out in the wilds of Loudoun County, tending bar, so the extended Willow family continues our peculiar fellowship. Jim is doing fine, by the way, and owner Tracy O’Grady passes along her best regards. She looked her Irish best in a cable-knit turtleneck sweater last night as she came out to greet the usual suspects at the Amen Corner of the bar.

I am fairly open to new ideas, which was evident at the bar last night, but I confess to having a passion for things that have gone before, and which still exist in our bewildering modern world.

That accounts, in part, for my fascination with the marvelous Mongol travel lodge- the “yurt,” and extends to how Arlington became a bedroom community to the District. I am a member and contributor to the Civil War Preservation Trust, which attempts to save historic farmland against the clutches of the developer community. During the boom years here in Virginia, the builders where quick to get the bulldozers on the property and knock down earthworks that remain from the time when DC was the most heavily defended town in the world.

It is really weird. My pal the Good Doctor has a chunk of the massive rampart of Fort Scott in his back yard, and if you know where to look, the ghostly shadows of massive earthworks and vanished military roads and sniper trenches still exist. They give a sense of the times long ago, now overwhelmed by the little houses of the 1950s and the McMansions that were thrown up in the hysteria of the housing bubble.

I had a real advantage in getting a perspective on historic buildings. Growing up in Detroit before it died/committed suicide, we made frequent visits to The Edison Institute (Henry Ford Museum) and Greenfield Village, where the wily old automaker actually had historic structures torn down and rebuilt in situ in exotic Dearborn. When the civic leaders of those towns recognized what had been stolen from them, I am sure they seethed in resentment, but it was cool to be where all those historic buildings wound up.

Thomas Alva Edison’s Lab from Menlo Park, New Jersey, is among the exemplars of heisted history, as is the original Wright Cycle Shop from Dayton, Ohio.

At the reconstructed Menlo Park complex, Edison himself recreated his invention of the incandescent bulb, and when he put down his tools on the workbench, they were never touched again by human hand.

The wizard of Menlo Park had his chance to play with affordable housing as well; Edison’s 1908 system of concrete construction is the best known example of a mass-produced concrete house. Edison envisioned an elaborate system of forms and machinery to pour a whole house in one swell foop: sectional cast iron forms bolted together were to be assembled on the foundation walls to the height of the house, ending in a central funnel into which the concrete was poured fresh from the mixing truck. Custom built-ins included concrete bathtubs.

It turned out to be too hard. Fewer than 100 were constructed; and even if it was not practical, many are still standing and inhabited.

I am not aware that the Lustron Corporation is represented in the collection of buildings at Greenfield Village. -It should be, along with examples of the Sear’s kit houses you could order from the catalog. Those are almost ubiquitous, and thousands of extent examples leap out at you in quiet neighborhoods all over the country.

The technologically sophisticated Lustron House (“The House America Has Been Waiting For”) was seen as a social policy solution for the dire post-World War II housing shortage. Here was the issue: millions of GI were being demobilized, and they wanted their old jobs back and to get on with life. The cookie-cutter development of Levittown was one approach to meet demand; here in Arlington, Francis Freed (“The Queen of Buckingham and Big Pink”) turned development of the Clairmont neighborhood on properties acquired by her late husband to her son. The Freeds began building little boxes to accommodate intense demand.

I will take you down there some time, if you happen to be passing through town. It reflects a different world view than the one we have at the moment, though that could change, and it will be the McMansions that look vaguely….obscene, you know?.

Both the Clairmont neighborhood here in Arlington, and Levittown on Long Island were totally integrated projects that borrowed from Allie Freed’s assembly-line construction methods, which in turn were adapted from Henry Ford’s manufacturing philosophy.

The Lustron corporation aspired to be something universal. Rather than selling the whole package- land and structure- Lustron wanted to take the Sears catalog approach to the next level, leveraging war production capacity to meet civilian demands.

Hey, it was after the biggest single nightmare ever experienced on the planet, and a great idea. Even the Government could recognize it. The homes were built entirely of steel in a former airplane factory using materials and technology developed during the war.

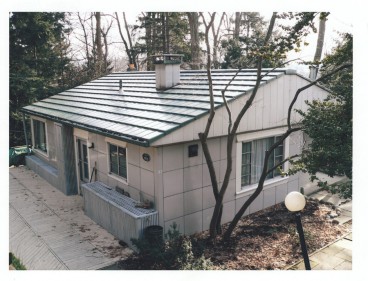

Interior and exterior surfaces were porcelain-enamel steel, sort of like your kitchen range or your dishwasher. Ditto for the roof shingles. The frame was all steel (garages had wooden joists) and the whole shebang was advertised to be “zero maintenance.”

Lustron homes sold for between $6,000 and $10,000, and all 3,000 pieces of the house arrived on a custom truck at the job site. The company manufactured about 2,500 of homes in three basic models between 1948 and 1950.

That might have made Lustron a candidate for Greenfield Village, but the company went bust in 1950, just like solar panel developer Solyndra. The Feds had over $12 million in special loans in the Lustron company, and considering that they were 1940’s dollars, it was quite an investment, just like the half billion we wasted on solar panels.

Lustron’s brief corporate life informs us about how all this science and technology comes together with Government patronage. It is an interesting backstory to a remarkable technology.

I will have to get that tomorrow. If I keep pounding on this I will lose my job, and be back to looking at yurt living.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com