(A MoTown 45 RPM Record. TM Motown Records or whoever owns the rights now.)

OK, we have done the city, done the region, all is not lost, well, maybe it is. But damn, Detroit was a vibrant place and it just seems like a crying shame that inept government, greed and a staggering level of drug and hyper-violent crime made it impossible for anyone to stay there who had the means to leave.

I mean, think of the legacy on so many levels. Sure, there were the astonishing technical innovations in manufacturing that changed the world and won a war. The social system, based on collective bargaining, that made it possible for a blue collar slob to actually buy the car he built, have a little place on a lake up North, and a decent retirement.

When I was working on the line, figuring out with numbing repetition that I had no interest what-so-ever in staying a Union worker on The Line, I listened to the tunes on the AM/FM radio I brought to the factory.

CKLW, the Big Eight, blasted 50,000 power-watts from the suburbs of Windsor. It was the iconic AM station the boomers grew up with. Pulsing with the beat of MoTown, the Canadian station could ignore the rules of the FCC and power over all in its path.

The Detroit stations- WKNR (“Keener 13!”) copied the format that spread all over- his Top 40 format was known around the country as “Boss Radio.”

“Keener-13” was a leading exponent of the signature MoTown sound in its peak in the mid-1960s, and I have to give a tip of the topper to the music that defines the legacy of the city to most of the rest of the world. It was core to coming of age for all of us, though the music was going to take us on a long strange trip before it was done.

I am going to get to what the white kids in the suburbs did with R&B, creating a gritty Detroit rock & roll sound from a vibrant aggregation of artists that includes Bob Seger, The Stooges and the irredeemably foul MC5. But chronologically, you should know what was coming out of the speakers in that GTO or Camaro, roaring down Woodward toward The Totempole or Mavericks.

(Barry Gordy, in the day.)

MoTown got it’s start with Berry Gordy, who was writing songs for local Detroit acts like the Matadors and the great Jackie Wilson. The latter hit gold with Gordy’s song “Lonely Teardrops,” which makes my toes tap even as I write. Gordy got screwed on the royalties (Welcome to Show Biz, Barry), and it occurred to him that the publishing and pressing of the records was where the money was in the business

(MoTown’s original location at “Hitsville” on West Grand Boulevard. A photography studio located in the back of the house on the left was converted to a recording studio in 1959, and Gordy lived on the second floor. Motown records expanded into several neighboring houses for offices, record production and rehearsal spaces. Photo Furious Freddy.)

In January of 1959, Gordy borrowed $800 from his family and founded Tamia Records. He wanted to use “Tammy,” but the franchise movie/record series with Debbie Reynolds had gotten there first. We used to watch those from the back seat of the Ambassador station wagon at The Oak Drive-in in Royal Oak.

(Oak Drive In sign on Woodward, two blocks from heaven.)

Operating out of his Hitsville complex on West Grand, Gordy engineered his first R&B success with Barret Strong, whose “Money (That’s What I want)” made it to number two on the charts. That song would be covered by dozens of white acts over the next decade, not surprising, since the pulsing base beat and unflinching honesty were dual signatures of the Motor City culture.

Under Gordy’s tutelage, the Matadors turned into the Miracles as Gordy gained confidence in a sound that had cross-over appeal to the top charts. The lead singer of the group was a charismatic young man who was briefly my neighbor in Palmer Woods: Smokey Robinson.

(Smokey Robinson in his early Miracles days.)

The Miracles’ first R&B hit “Shop Around” peaked at number two on the Billboard charts and #1 one on the R&B. It sold a million copies. Gordy and Smokey were on their way, and the hits kept coming. “Please, Mr. Postman” scored for the Marvellettes. A trio of talented writers, Holland-Dozier-Holland, generated snappy tunes that appealed to an America that wanted to dance and was spending a of of time at the wheel.

I defy anyone to sit down and listen to the greatest MoTown hits of the 1960s to not want to get up and start lip-synching. Gordy had more than a hundred top-ten hits with artists like The Supremes, The Four Tops, the Jackson 5, Mary Wells, Little Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye and the immortal Temptations.

The MoTown sound influenced the next wave of music as well. Bob Dylan called my neighbor Smokey “America’s greatest living Poet,” and Beatles John Lennon and George Harrison were both admirers of his sound.

The year I moved back to Detroit was when that was ending, though. Smokey Robinson and The Miracles gave their last concert in DC in 1972, and Smokey went on to a solo career of slow, smooth R&B. He charted his first solo LP “Smokey” that year.

Nothing goes forever, though, and everyone knew there was something going wrong with Detroit that year that good music all by itself could not heal.

Gordy got the hell out of the Motor City himself in 1972, and moved to LA. He continued to operate the label as an independent until 1988, when he sold it to MCA, and God only knows who owns the catalog of music that channeled the Delta through West Grand Boulevard and into our collective souls.

CKLW and Keener 13 were passé by 1972 anyway. On February 1, 1968, a little station with the call letters “WABX” ditched the “play list.” The DJs picked their own tunes and “ABX” became the icon of Freeform Progressive Rock. That is what was playing on my AM/FM clock radio on the line when I was there, not CKLW. ABX boomed and popped with surprise, airing new music no one else was playing.

Try Iron Butterfly, the full-length version of “Light My Fire” by The Doors, Jimi’s snarling, wailing electric guitar. Traffic, Cream, all the bands that represented the nastier side of the anarchic British Invasion.

Sex , Drugs and Rock Roll, anyone?

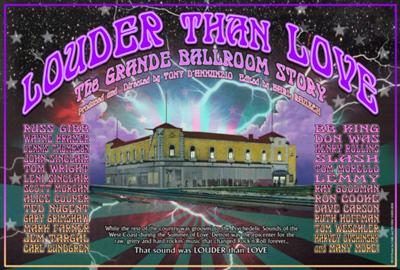

Oh, man. We will take a trip to the Hideout in Harper Woods tomorrow, where Bob Seger and others got their start. And the Hideout only sets up the titanic struggle between the Eastown and Russ’ Gibbs legendary Grande Ballroom. There, in the old palace, could be seen the most amazing sights a teenager could see.

In the unisex restroom of the Grande Ballroom between sets quite literally anything in the world could be going on. And it was.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com