Ruin Porn

“At the end of the 2007 school year, Jane Cooper Elementary (built in 1920) was left unsecured in the middle of the wasteland where a middle-class neighborhood once stood. It took “scrappers” only a few months to strip the building of every last ounce of metal and leave it looking as though it hadn’t been occupied for decades.” Ruin Porn Philosopher James Griffieon, quoted in the on-line Vice magazine.

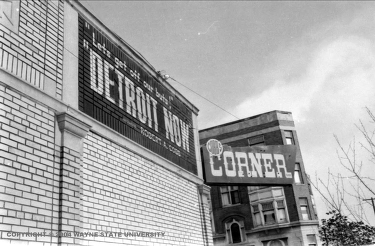

I will be up there to take my own pictures in a few weeks, or not. The image above pretty much sums up the concept of what the fashionable are calling “Ruin Porn.” It is a new sort of forbidden pleasure, viewing the abasement of a once mighty city with a certain almost erotic pleasure.

Schadenfreude might be the best way to sum it up: pleasure derived from the misfortunes of others

Philip Levine’s famous poem, “What Work Is,” comes to mind. My pal bonds sent it out as a reminder, in its entirety, but it starts like this in stark reality:

“We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is–if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.”

It is a powerful poem about a gone world. The Ford Highland Park Assembly Plant was designed by the legendary Detroit architect Albert Kahn, whose graceful factory designs defined the might of the city.

(Ruin porn view of Albert Khan’s Packard Plant, which featured lots of glass and integrated concrete structure.)

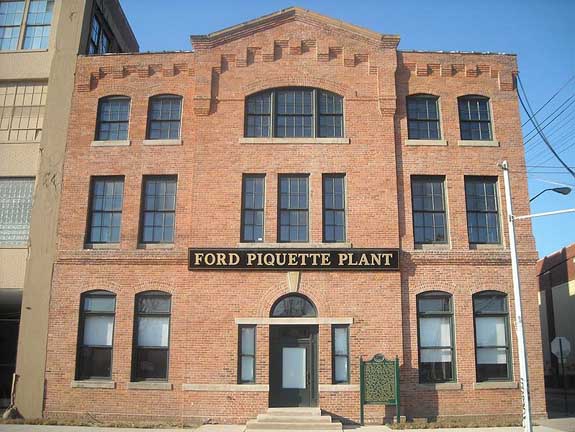

Kahn began his career in 1907, when he was commissioned to design a new plant for the upscale Packard Motor Company. Henry Ford liked the concept, and commissioned an improved model for a site in Highland Park, a civic enclave surrounded by Detroit just off Woodward south of McNichols. Ford moved from his original plant at 411 Piquette Street to the Park, and changed the world.

Ruin Porn folks like to show the Model T plant like this:

But like all the porn shots you have to crop the photos carefully to make sure you don’t tell the wrong story. Here is the new CVS strip mall that has been added to the vantage:

(New CVS Strip Mall in “Model T Square.” 2010)

When the Highland Park factory became too small, Kahn designed new Ford plants just south of Detroit — the River Rouge Complex, which opened in 1927 and held 90,000 workers. It was the biggest industrial plant in the world at the time. Driving I-75 out of the City, as I have hundreds of times, the vast complex never ceases to amaze me, and it was still there the last time I looked.

Kahn was not restricted to industrial work, and his designs were ubiquitous around the area. The SS Kresge World Headquarters downtown was a splendid example. It was the home of Detroit Institute of Technology when I used to visit, but he did hundreds of residential and office buildings around town.

Sad, really, to see then cast aside. Kresge moved out to Troy, and then it got it’s lunch eaten by the monster that is WalMart. I don’t think the new building is abandoned; they don’t do things like that in the City of Tomorrow, Today!

The blight of the crack wars of the 1980s drove most of the rest of the town into ruin. The City became a cartoon hallucinogenic landscape in Robocop, the iconic Peter Weller film set in “In a dystrophic & crime ridden Detroit, a terminally wounded cop returns to the force as a powerful cyborg with submerged memories haunting him.”

I think most diaspora Detroiters took a certain grim pride in things being that bad, and the film, with the exception of some exterior shots, was actually shot in Texas someplace.

The flight from the city included even those who cannot walk. Families who fled Detroit for the suburbs in the 60s and 70s did not want to return to visit their dead. An active industry in disinterring the dead has sprung up in Elmwood and Mt. Olivette cemeteries and relocating the dearly departed to suburban graves. According to the wondering story on the AP, more than a 1,000 bodies have been exhumed and moved since 2002.

All that said, and goodness knows there is a lot more to say, there is energy in the old burg yet. The industry that so effectively mines derelict structures for scrap metal is one of astonishing vigor. The Jane Cooper Elementary School that sits in the midst of one of Detroit’s urban prairies is a case in point. Abandoned by the School Board only in 2007, the place was stripped of all recyclable material in months.

Still, the photographer who captured the image said he had to be careful to crop the frame. In the midst of the seeming endless expanse of waste, there is a modern and functioning factory to the left of the frame, and a strip mall with activity to the right.

After suffering through decades of racial violence, industrial collapse, serial arson, crack wars, and years of municipal kleptocracy, Detroit is now the destination of choice for Ruin Porn. I am guilty as any in having a grim fascination for the image and metaphor of decay, but it simmers with resentment toward what was done to an old friend. I don’t share the same motivation as, say, the Germans and Japanese who seem to delight in the downfall of the city that armed their one-time tormentor.

So, I was going to organize a “fabulous ruins” tour when we go to the conference in the Motor City in a few weeks. I still will, but there is more nuance to all this. Dave Bing the great former Pistons basketball player is the mayor now, and there is no reason for him to have to grift the city for spare change.

The Greektown casinos and the famed Elwood Grill are still going strong. The Fox Theater glitters with restored Art Deco elegance. I am not saying that the city is coming back, but it is not the story you get from the ruin pornographers. I mean, there is another way to look at it.

Here is the interior of the Ballroom of the famed Book-Cadillac Hotel in porn:

Looks pretty post-apocalypse, right?

Well, here it is the way it looks right now:

(Photo courtesy Westin Book-Cadillac, 2010.)

The Westin people put their money where their mouths are and they fixed it. So, who knows. Where there is life, there could be hope.

Even those boneheads we elected to Congress figured something out and alternative with an hour to go before they locked themselves out of Capitol.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Ludicrous (and Cruel)

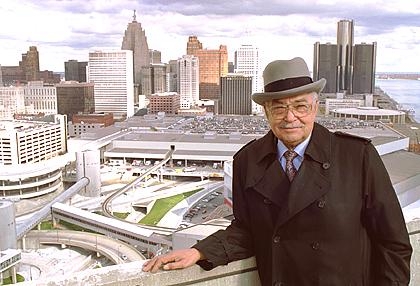

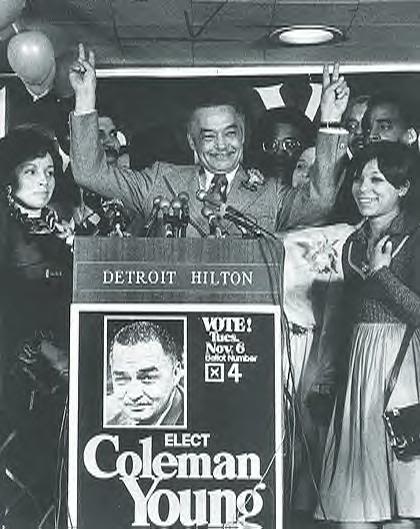

(Detroit Police Chief William Hart and Mayor Coleman A. Young in better days. Photo Detroit Free Press.)

When you grow up in a town north of Canada, all directions are down from the Pole.

That is the way it seems, anyway, since the accident of the Detroit River and the protrusion of Ontario below the tumescent bulge of Michigan’s thumb placed the little Canadian town of Amherstberg due south from where Big Beaver Road intersects Woodward in Grabbingham.

It is across the river from the approach to Naval Air Station Grosse Isle, where Raven flew his Douglas A-1 Skyraider back the day, and the distinctive diamond of runways still beckons from the port windows of the airliners that take me home to DC from the Motor City.

It is all downhill from here, too, these days. Those morons on the Hill are continuing to screw with us. There were conference calls at the office yesterday to deal with the apparent inevitability of a government shut down. That train-wreck has been in progress for so long that now that the moment has arrived, again, it seems a but unreal.

I mean, with majorities in both houses and a Democrat in the White House last year, they idiots could not deliver a budget. Now with the other sort of loons in control of the House, we are somehow in a major policy fight about the funding of Planned Parenthood.

I know there are strong feelings on both sides of the issue, and respect the emotion. But, hey, take it outside, would you guys? We are facing the biggest national security threat of our lifetimes in the form of a budget deficit that will destroy our currency and you idiots appear ready to sacrifice the country over something that is none of the Government’s goddamn business in the first place?

It is beyond sanity. The litany of criminal greed that got us to this sad place has been abundantly documented. The Bankers who stole our cash are unpunished. The corrupt legislators who took their money and cooked the tax code are still in office. The Administration seems to live in a cloud-cookooland that imagines that a budget relying on a 40% deficit sold to credulous Chinese is somehow acceptable.

What is not sustainable is…well, not sustainable. That means this collective lunacy is going to end at some point. That can be done, in my feeble understanding, either in a grown-up and orderly manner, or in a panicked catastrophe when the illusion of normalcy dies and the rush to the exits begins.

Paul Krugman, the Nobel Laureate and known smart guy, shot holes in the House budget plan formulated by Rep. Paul Ryan. He castigated those who had applauded Ryan’s effort to reign in the deficit, acting on recommendations formulated by the bi-partisan Bowles-Simpson panel, but which could not pass an internal vote due to the unpalatable nature of the options that could salvage eventual solvency.

(Paul Krugman. Photo Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times.)

I borrowed Mr. Krugman’s title for the hysterical rant this morning, since he rightly points out that some of the provisions of Mr. Ryan’s budget are simultaneously ridiculous and heartless. Of course he is right, just as the Erskin-Bowles panel was. This is not going to be fun. In fact, it is going to be ludicrous and cruel to a lot of people, you and me included.

The view from the city north of Canada is illuminating, and revisiting the disintegration of a city that once seemed too big to fail is useful to look ahead and see what might be hurtling down the wrong side of I-75 toward us.

Back when I lived there, the illusion of Detroit as a viable enterprise continued for a while, though the paradigm shifted from making things to stealing them. There is, today, a continuing industry in mining the old skyscrapers and single-family homes for scrap metal.

Mayor Coleman A. Young had a vested interest in continuing to drive the once-great city into the dirt. The more unipolar the city became in demographics, the stronger his power base became. There was plenty of stuff to vacuum up in the great deconstruction, at least for his twenty years in office, plenty of swag to spread around to his pals.

The Mayor was an outspoken advocate for federal funding for Detroit construction projects, and the legacy of the free money, unconnected to any organic generation, saw the erection of the RenCen, the People Mover and the Joe Louis Arena. Construction funds offered plenty of opportunities for graft, and the corruption was endemic to the enterprise.

Police Chief William Hart was one of the beneficiaries. He was convicted of stealing two-and-a-half million dollars from the undercover activities funds. Deputy Chief Kenneth Weiner was busted for embezzling $1.6 million from the police pension fund.

While the Blue-Suiters had the highest profile in criminal activity, there were dozens of other investigations, indictments and convictions in the Young Administration. The corruption in the school board and sanitation department are legendary.

You can’t call it anything other than officially sanctioned looting.

Upon learning of Young’s death from emphysema in 1997, former President Jimmy Carter called Young “one of the greatest mayors our country has known.”

By that criteria, I suppose you could argue that Jimmy was one of our greatest presidents. But I digress. The consensus these days is that the death of Detroit was somehow inevitable, even a necessary event. Maybe that is true, but if a city as amazing and vibrant as Detroit, a place too big to die, does anyway, maybe that is likewise true for other really big things.

Like the good old USA.

Nah. Couldn’t happen. We are too big to fail, right? Someone will bail us out. Maybe Goldman-Sachs….

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

The Line

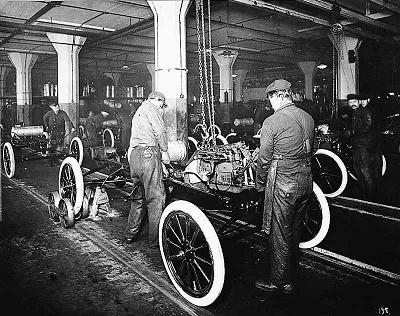

(Ford Model T assembly line. Photo FoMoCo.)

With all the talk about jobs these days, it makes a Boomer sigh. We have all done some work we didn’t like much, but we lucky ones got a chance to see some things that really suck. I worked on a farm one summer, and that was an eye-opener. It was hard but at least it was outside.

The work in Detroit was hard-core at its very soul. There was outdoor work that our brief resumes qualified us for: laying asphalt or grounds-keeping were ones that most of the guys had a chance to try their hands at. Nothing quite like a Michigan summer day and red-hot black top. Thankfully, Michigan skies are gray most of the time due to the moisture from the lakes that surround the peninsula.

In the summer of 1969 one of the Dad’s who was a wheel at Chrysler got Muhammed and Beau Diddley and Max and Max’s brother jobs on The Line at the Dodge Truck on 9mile and Mound.

They worked there all that summer after high school- no air conditioning in the plant, hot as hell, and they dragged themselves back to plush suburban Grabbingham exhausted after every 8.5-hour shift.

Pocket was there at the same plant, same awful repetitive motion for eight months, bridging some time between stints at Eastern Michigan in Ypsitucky, which is what we called the adjoining city to Ann Arbor due to the high concentration of crackers who had come to work in the Willow Run plant building bombers.

The rhythm was the same in every UAW plant, and it was one that had been negotiated on the sweat of working people from the dawn of The Line at Henry Ford’s Model T plant in Highland Park.

The plant is still there, as is the original little factory at 411 Piquette Avenue. Surprising, really, since so much more has been demolished. They say that 50,000 factories have been knocked flat.

The plant where I was on The Line is gone now, knocked down a couple years ago. We got the same two paid fifteen minute breaks and one non-paid 30 minute lunch.

The work was mind-numbing, and we regularly screamed out of the Kelvinator plant to hit the Silver Slipper and see how much beer we could drink in the twenty available minutes inside the tavern. Working in the plant was like being condemned to some awful eternal now of timelessness.

But as bad as The Line was, it paid enough for the people who worked there to buy the products that came off the end of it. The work molded the character of the town, and while the attitude still remains, those days are gone. That is what polished off the city, the last decent jobs being devoted to knocking down the big plants.

And now, for the most part, it is all gone, vanished.

Back then, when I did the six operations on each shell that marched, inexorably, toward me and then into infinity, I had the radio behind me cranked up to CKLW, The Big 8, and the music kept me sane.

Or something. More about The Beat tomorrow…

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Bailing Out

I stopped at Willow after work, no surprise, still thinking about the husk of the city. I had looked for a limo to do a tour of some of the ruins, a delicate matter, since those that dwell too deeply on what is so sad are said to indulge in a fetish called “ruin porn,” and there is life in the old town yet.

Not like it was, goes without saying. I walked in and saw Old Jim anchoring the bar, another non-surprise, and after he told me to go fuck myself, he said he had checked the site for the latest bloviating and was vaguely interested, since he had spent his time in MoTown, back in the day.

I asked him when, and he said: “1979. I lived about a block from 8 Mile. Two bedroom apartment. No furniture.”

“You slept on the floor?” I said, not surprised.

Jim nodded, beetling his formidable brow. “I had a gig for a year as Lee Iococca’s speech writer. We were trying to sell the bail-out to the government.” He paused and took a sip of Bud from the long-necked bottle in front of him. “The bail-out before this one, back when Lee had to convince the Congress to guarantee the loans to save the company.”

“He was a great guy,” I said. “Fucking iconic. He joined Ford’s with Dad’s class, right after the war. He was in Engineering, but made his bones in finance and marketing. He was a pistol.”

Jim nodded. “He got crosswise with Henry Ford the Second over the mini-van idea.”

“Yeah,” I said, sipping some of the happy hour white. “The Deuce was a piece of work. He couldn’t get the car business right anymore than he could the Lions. They made a couple billion the year he fired Lee. That was the year after I joined the Navy and bailed the hell out of Michigan for good. Then Ford’s went into the wilderness in the recession of 1980 recession. What did they use to say? “FORD” stands for Fix or Repair Daily.”

“Lee brought the K-Car and the mini-van over from Dearborn, and revolutionized the industry. We managed to sell the loan guarantee, he delivered the product and they paid the government back seven years early.”

“I was gone when that all happened.” I grimaced. “I always preferred the station wagon to the mini-van, but anyone with kids wound up with one sooner or later.”

Jim contemplated his beer. “There was no furniture in the place I rented and never got around to going to Art Van’s to buy any. I didn’t think I would be staying, or at least I didn’t know about it. I was making $70 grand for the year.”

“That was a lot of money in those days,” I said. “The biggest raise I ever got from the Navy was when I made Lieutenant for pay. It was enough to make me not bail out, but I didn’t make seventy grand until I was a Lieutenant Commander, and that included the living allowance.”

“I wasn’t going to fit out a whole apartment, but I had my self-respect,” said Jim. “I stopped at a toy-store and bought some doll-house furniture. I had a gal over to the apartment one night and asked her if she wanted to see my Queen Ann’s bed. She said she wouldn’t mind, and we went into the bedroom and I showed it to her. I had the little thing over by the wall.”

“She must have thought you were crazy.”

Jim nodded, smiling at the recollection. “Then I asked her if she wanted to see the Swedish Modern, and I took her in the other bedroom and there was the little bed and a tiny set of drawers.”

“I take it that did not get her in the mood to get on the floor with you.”

“No, she just wanted to get the hell out and she bailed.”

“She must have thought you were crazy,” I said, imagining the young woman’s growing discomfort and flight into the night.

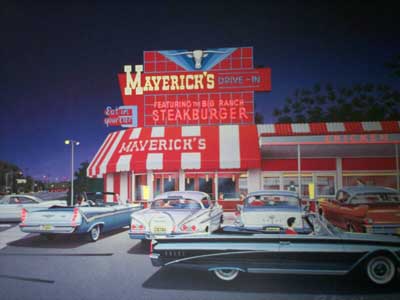

“Probably. I went out after that. Went to Maverick’s on Woodward and had some more drinks.”

“Mav’s was a drive-in when we used to go there in high school in the muscle cars. Nothing like a Charger 440 RT Hemi with the little tray table hanging off the window. I remember the standard order: “Billie, Fries and a Coke.” The waitresses would bring the food out to the cars and there was nothing finer than looking at the other kids in their cars and chowing down.”

“It was a bar when I knew the place in 1979,” said Jim, “and I liked that better.”

“Were else did you hang out? The Lindell AC downtown?”

Jim nodded. “Oh yeah. Great place after a hockey game at the old Olympia rink, or a Lion’s game at old Tiger Stadium. Lee always had great tickets for everything, one of the perks of being a Detroit CEO. I was interested in the Octopi flying out of the stands and onto the ice from the seats up by the roof at Olympia. Great tradition. There was a place in Bricktown that was furnished with car parts. But there was a place in the New Center I really liked, in the Fisher Building across from GM Headquarters. It was on the first floor, but sunken down. I don’t remember the name but I saw the best leadership by a bartender ever there one night.”

Dorothy the straw-haired single lady was finishing her plain salad next to us when an astonishing thing came out of the kitchen on the arm of Armando the waiter. It was a lobster tail piled on something interesting and wearing what appeared to be a little yellow garnish like a hat. The presentation was magnificent, just like you would expect from Tracy O’Grady’s kitchen.

“So, what did this bartender do?” I asked, after documenting the presentation on my cell phone camera.

“It was pretty cool. There were about five hundred people crowded in the place, and a belligerent drunk was hassling everyone. The bartender was old school, white apron and white shirt and one of those muscular little tight black bowties. He brought the drunk a fresh drink and waggled a finger like he wanted to say something.”

“And?”

“When he did, the barkeep grabbed the asshole’s long tie, jerked him forward, took an icepick and plunged it down- thwack!- through the tie and an inch into the mahogany bar. Then, with the drunk pinioned in place, he rocked back and slugged him hard enough in the face to knock him out.”

“That is why I wear bow ties,” I said firmly. “It is a matter of personal safety.”

Jim nodded. “Then the bartender looked up at the crowd and said “Anyone got a problem with this?” and the crowd went wild and applauded.”

“That is my Detroit,” I said. “High sticking and hard elbows.”

“Good music, too,” said Jim. “Did I tell you that is where I met my wife? She was a chanteuse.”

“Really?” I said. “Mary is an attractive lady, but I had no idea she was in show business.”

“Yeah, I met her when she was playing at Ramparts on Woodward.”

“Was that the titty bar next to Chaldea town?”

“No, that was the place next door. Mary was a respectable artist.”

I nodded. I can’t for the life of me remember the name of the gentleman’s club by the State Fair grounds right next door to Ramparts. They had great hamburgers, if I recall properly. But of course, that is not all there is to recall about the end of days in Detroit. I finished my wine and decided to go home and play some old MoTown on the iPod and look at the stars.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Black Bottom

(Detroit Skyline, 1929.)

Writing about Detroit means writing about The Line. Manufacturing stuff was what provided the economic base that produced the graceful boulevards and avenues that made the city once called- without irony- “The Paris of the Midwest.”

Detroit ranked third in the nation, after New York and Chicago, in the number of major buildings erected during the Roaring Twenties. The boom proved dramatic and lasting.

In 1919, General Motors began construction of its new headquarters, the largest office building in the world at the time, followed by the First National Bank Building in 1922.

The Penobscot Building, begun in 1928, was the tallest in the city for nearly 50 years, until the RenCen went up. The Book brothers transformed Washington Boulevard into a replica of New York’s Fifth Avenue. The Book Cadillac Hotel at Michigan and Washington was the jewel of the city hotels. In 1928, the beaux-arts Fisher Building, across the street from the General Motors Building, provided a commercial anchor.

Of course it was the factories that made the Motor City one of the major termini of the Great Migration from the south. Whites from Appalachia and the upper south came during the Roaring Twenties and settled in places like the Cass Corridor.

African Americans came to the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley nieghborhoods of the Near East Side. That was a bounded by Gratiot Avenue, Brush Street, Vernor Highway, and the tracks of the Grand Trunk and Western Railway. The main commercial strips were Hastings and St. Antoine streets, which Coleman Young knew well as a young man since his father operated a small dry-cleaning shop and worked a second job as a night watchman.

That was the way things worked if you were going to take care of a family, and did not live in one of the grand houses in The Indian Village, or work in one of the proud towers that were thrust up in the Roaring Twenties. Working shifts was what Detroit was all about when the factories roared around the clock, and when they did not, times were tough. The Depression hit Black Bottom hard. Strict covenants and the practice of Red Lining contained the black population there, and the area began to fray at the seams and even the recovery of the war years only made the pressure for decent housing worse.

(The 606 Horse Shoe Bar in Black Bottom.)

By the time Raven and Magpie were able to move into the city from Ferndale in 1954, Black Bottom had a vibrant community of black-owned business, social institutions and night clubs. By day, the center of black Detroit was exactly that. But by night, the neon lights, jazz and blues drew white crowds. Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstien and Count Basie were regulars, and Ella Fitzgerald were regulars.

Aretha Franklin’s father, Rev. C.L. Franklin, opened his New Bethel Baptist Church in the heart of Black bottom.

Night-life aside, pressure on the housing market caused middle-class Black to move north and west from the neighborhood. The real estate shenanigans that went along with block busting chased my folks out of town and up Woodward to Grabbingham. They were only renting in the Motor City, not trapped with a mortgage like Clint Eastwood in “Gran Torino,” the movie filmed right there.

Black Bottom became a seriously blighted neighborhood. Grand visions of a renewed Detroit destroyed virtually every vestige of Paradise Valley and Black Bottom as Interstate 75 plowed through the area in the 1960s.

I mention that because of what my pal Muhammed recalled the other day. He got out of town in 1973 while the getting was good. He remembered driving around in the Vega Kammback on a few occasions, before he left for Arizona.

He remembered something I didn’t. “One night we piled into the Vega for a very speedy drive home from a night Tigers’ game. I think on the way to the game you were still observing a 55 speed limit till the car hit a certain number of miles and was broken in. I think you blew off that limit and drove 85 the whole way home. I remember the Vega as one of the first “tin can’ type small cars I had ridden in other than a VW bug.”

Oh, man, I had not thought about the old ball park in a while, nor the time on The Line that we all spent building those pieces of crap.

Tiger Stadium is gone now, too. Along with all the jobs on the Line. And the reason I mentioned Black Bottom was that we passed the Jeffries Projects that night on I-75, rocketing through what had been a neighborhood and now is just crumbling concrete and asphalt.

We were all UAW workers, too. Went with the territory. I will have to get to The Line and Solidarity Forever tomorrow, I guess.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Cass Corridor

(1973 GMC Chevy Vega Kammback Wagon. Photo Socotra.)

I can’t talk about the creation of the fabulous ruins of Detroit without mentioning the ride I had at the time. Raven bought it, brand new, and gave it to me to ensure that I had reliable transportation to get to work. It was part of the civil contract we had between the generations to transition me from dependent to working citizen.

It was the model for the contract I had with my boys, and hope that they, in turn, can carry it off for their kids, should they ever get around to having any.

I had to think about that when I was signing the title for the Bluesmobile over my younger boy on Saturday. It was a strange enough day as it was. The Title was crisp from my files. My son needed it because he couldn’t stand the vanity plates on the car that feature the big block “M” of my alma mater.

He is a proud Spartan, and was incensed at the idea that people might mistake him as a Wolverine as he thunders around the Beach town in the Police Interceptor.

One thing led to another as he sought to replace the tags with something more neutral. We finally agreed on the “Fight Terrorism” logo for the new plates, which is rational enough, since that is the business I retired from and the one he is going into.

Unfortunately, the Commonwealth insists that his name appear on the pink slip in order to do so. That is why I inked in “$1” in the “price sold” block and signed the car over to him. The Virginia pink slip is green, of course, the color of my 1973 Vega.

I still think fondly of that car. It was a piece of crap, of course, from the great age of Detroit rolling pieces of crap. 1973 might have been the peak year for lousy quality control and UAW workers with attitude. Remember? We used to say we didn’t want a Monday or a Friday car, which was to say, the work-force was notoriously careless in the assembly process coming back to work after a hard weekend, or getting ready to party on the weekend.

The Vegas were thrown together at the plant at Lordstown, in Eastern Ohio. I see the plant every time I drive up to Michigan, but it is far enough away that I could not get down there to see them put the Kammback Wagon together, or know precisely what day they hammered it together.

I still think it was a good-looking car. ’73 was the last year the Feds did not require those ugly rubber energy absorbing bumpers, which were ugly as sin and didn’t really catch up with the rest of the design for years. The mini-wagon design flowed nicely and gave a lot of room to throw stuff in the back, sleeping bags and old liquor boxes filled with LPs and college textbooks for the job.

The 1973 Vega model year featured over 300 changes, including new exterior and interior colors and new standard interior trim. I ordered the tan interior and British racing green for the exterior paint. The four-speed manual shifter was from Saginaw Steering Gear, and a new shift linkage replaced the Opel-built units. The L-11 engine featured a new Holley staged two-barrel carburetor.

I specified the BR70-13 white-stripe steel belted radial tires for the Kammback Wagon, and thought I was pretty cool rolling down Woodward or the Cass Corridor in my little car. It was quite a change from the muscle beasts we learned to drive in. Small was beautiful in the days of the even-odd gas lines, a thoroughly un-American restriction on our traditional ability to drive anywhere at any time.

Much as I liked it, the Vega was a piece of crap. It burned half a quart of oil for every tank of gas, just like clockwork. It was not shoddy workmanship, though, it was that the Vega engine was not ready for prime time, which was true of the whole industry that year.

GM Research Labs had been working on a sleeveless aluminum block since the late ’50s. The incentive was cost. Engineering out the four-cylinder block liners would save $8 per unit. Reynolds Metal Co. developed a custom alloy suitable for faster production die-casting.

The Sealed Power Corp. developed chrome-plated piston rings specially blunted to prevent scuffing. It might have been a successful design, with a little more time for development, but the OPEC embargo prevented that. Demand for fuel efficiency was suddenly really important and the engine was rushed into production.

Who could have imagined that V-8 powered Detroit would suddenly have an immediate and pressing need for four cylinder engines?

I tried driving 55 on I-75 the morning after President Nixon announced how important it was that we conserve energy. I was nearly run over by a Buick hurtling toward the Livernois exit. I was so young that I took things the President said seriously.

(Cass Corridor landscape. Photo Detroit news.)

After that, I preferred to motor more sedately down Cass when I visited the Wayne State University campus. Cass Avenue runs parallel to Woodward, which is the golden road out to where white Detroit was fleeing, out toward Grabbingham and Bloomfield Hills and the mansions of the car people. Cass runs from Congress Street, ending a few miles further north at West Grand Boulevard.

(Detroit’s famed Masonic temple. Photo Wikipedia.)

Significant landmarks along the fourteen blocks that constituted the Corridor included the Detroit Masonic Temple, which looks like a church but is actually the world’s largest building of its kind, and Cass Technical High School and the small but densely-packed Chinatown. The architecture was 1930s-industrial, for the most part, and low apartment buildings and tons of bars and restaurants.

(Cass Tech High School’s old building.)

The area was populated mostly by white southerners and their successors, who had come north during the war. There were Hindus and Native Americans, burned-out hippies, students from Wayne State and single-moms struggling to raise their kids.

Immigrants from India, Pakistan, China, Korea and the Philippines were part of the mix. Many worked at the Detroit Medical Center, a group of hospitals just across Woodward Avenue.

Detroit’s small Chinatown was located at Cass and Peterboro in the southern end of the Corridor, and there was often a wait for tables at lunch.

That was during the day. The proximity of Cass to Woodward, Detroit’s main artery, had made Cass the logical area for the local authorities to push local drug activity, prostitution, and general civic indecencies away from the downtown.

Long-legged, high-heeled hookers, predominantly white, prowled the sidewalks outside world-class dive bars like Jumbos, The Sweetheart, Willis Show Bar and Anderson’s Gardens. The Gold Dollar Show Bar advertised “Female Impersonators Nightly.”

Crazy was OK. Prime-time sidewalk shows featured the working ladies who would flash their breasts at the Johns driving in from the suburbs, their pimps, winos, scammers, dopers and dealers.

The bars- particularly Anderson’s and the Wills, were all paying for active police protection, and despite the seedy nature of the neighborhood, I never felt bad about going down and hanging out. I used to love to take visiting Book Company people to Anderson’s Gardens. It gave them a thrill, but I knew the place was 100% safe.

At least it was then. As inauguration day rolled around for Coleman, and as Dick Nixon lurched through the last anguished days of his presidency, things were about to take a dramatic change, courtesy of the scourge of crack cocaine. But I will have to get to that tomorrow. Here is a taste of what is to come:

“In a very real sense, the mayor of Detroit and the Detroit media serve different constituencies. The media seem never to have recognized that. The reporters talk about Detroit as a large metropolitan area spreading far from the city center. Coleman wasn’t elected by those people. In the view of the Mayor, the media represent an outside set of interests-interests which should be treated with suspicion. Given the social geography of the metropolitan area, there is a racist relationship between the media and the city.” Wilbur Rich, in “Coleman A. Young and Detroit Politics”

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

The Mayor for Life

(Coleman A. Young stands atop the Riverfront Apartments he encouraged as Mayor. Detroit Free Press photo by Tony Spina)

So, Coleman Young grabbed Detroit by the throat and shook it so hard that the fifth largest city in These United States had its neck broken.

Nah, didn’t happen that way. Walk with me back a little to what happened a couple weeks before the State Senator made history by becoming the first African American elected to preside over a major American city.

Sort of seems quaint these days, but it was a big deal then. Atlanta followed within ten days, electing Maynard H. Jackson, Jr., over an avowed segregationist by a significant margin. Jackson’s majority included a third of the white vote.

The nation was adjusting to the change in demographics brought by the riots of 1968. In Atlanta, the electorate chose progress. In Detroit, ten percent of white voters went with the vast majority of blacks who hated the terror of the STRESS unit. That was the first thing that went when Coleman Young was sworn in as Mayor in 1974, and with it went the plurality of white citizens of the city.

It was one of those moments when an earthshaking event emerges from the ballot box. That was what was out in the open, and reported breathlessly by the media. There was much more that swirled out of conflict in the Middle East. A buddy was at basic intelligence school that Fall. In the shadow world, the two superpowers of the time moved toward confrontation over the Yom Kippur war.

He recalled that “…once the Israelis regained the advantage and crossed over into Egypt, the Soviets went to one step below Full Combat Readiness and began to generate their combat forces to include moving airplanes and ships to dispersal locations and forward deployment.”

Under the muscular Kissinger-Nixon leadership, the US countered by declaring DEFCON 3. There are five levels of Defense Condition. Mostly, we are at the lowest level, or “5.”

For those in the business, the order to go to “3” meant that the great machine was ratcheted up significantly. During the Cuban Missile Crisis the U.S. armed forces as a whole were ordered to DEFCON 3, while the Strategic Air Command was elevated to “2.” That means the bombers are aloft, on station, gas is in the air and pulses are throbbing. This was only the second time the whole machine went to “3,” and it would not happen again until 9/11.

“It was a scary time,” my friend confided, “since no one knew what would come next. There were whispers that we would get a truncated round-the-clock version of schoolhouse spook training and shipped out.”

Against the stark backdrop of increased nuclear readiness, the ministers of OPEC shut off the pipelines and the price of oil skyrocketed like ICBMs. You had to be there to get the sense of it, but imagine having an empty tank and nothing and no way to fill it.

There is no physical shortage of oil these days. I marveled at the price of gas yesterday when I made the weekly pilgrimage to Fort Myer to top off the tank of the Hubrismobile. I looked blankly at the price for Hi Test- close enough to four bucks a gallon that the difference was insignificant.

But I could buy all I could afford. That was the difference then. You could not get it.

In Detroit that disorganized fall there were so many things happening that it seemed the world was teetering on the brink. After the domestic craziness of the 1960s, there was the looming reality of the first military defeat in American history, a Presidency in the process of unraveling, and the sudden realization that we no longer controlled something as basic to our liberty as driving the Chevy down to the Levee.

The tank was about dry.

(Vice President Spiro Agnew.)

Do I have to remind you that Vice President Agnew had to resign just a few weeks before Coleman Young was elected? That is a footnote that is not an irrelevancy to the man who strode up to the podium to take command of the fifth largest city in America, the home of the Big Three car makers, and the emblem for Mom and Apple Pie.

It is worth a brief profile of the man who would become Mayor For Life of Detroit, and the historic role he played in its decline, periodic resurrection, and ultimate desolation.

There is much that is admirable about Mr. Young. His Dad brought the family north from Alabama in 1923 as a response to the violence of the Klan and the suffocating institutional racism of Tuscaloosa.

An Army veteran of the war, he infused in his son a sense of outrage at the basic unfairness of the system. That was exacerbated by the treatment Coleman experienced in the parochial schools, ultimately having to return to public education to graduate from Eastern High School.

Lack of scholarship money meant that he could not attend the University of Michigan. He was a Progressive (at a minimum) and dabbled with the outer left fringes of the movement, attempting to organize workers at Ford’s and the Post Office. With the coming of the war, he sought a commission in the Army Air Corps and was one of the famed Tuskegee Airmen. He also was a determined activist, and participated in one of the first social actions of what would inspire Harry Truman to end the official segregation of the US Military: the Freeman Field Mutiny.

(African American Officer line up after arrest.)

(African American Officer line up after arrest.)

In that event, African American officers were arrested a total of 162 times for attempting to integrate the Officer’s Club at the air base at Seymour, Indiana. Upon demobilization, Young returned to Detroit to explore a variety of avenues to political power. The one that worked was the Con-Con: Michigan’s 1960 effort to reform the state constitution.

That was a bizarre intersection between Magpie and the future Mayor, since the chapter of the League of Women Voters she chaired in Grabbingham was influential in the convening of the convention. I remember carrying signs in support around the little suburban town, part of George Romney’s successful effort to transition from businessman to statesman.

(Raven’s Boss, George Romney, Governor of Michigan.)

From Con-Con, Young ran for State Senate, won, and positioned himself to become the ultimate powerbroker in a doomed town. It was fascinating to watch, a Motor-City version of the passion play that Marion Barry later ran in Washington, DC, to the horror of the people who worked in the government but did not live where they labored.

That is worth a little discussion as all the roads lead out from 1974 into a future that still does not seem real at all.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Dark Side of the Moon

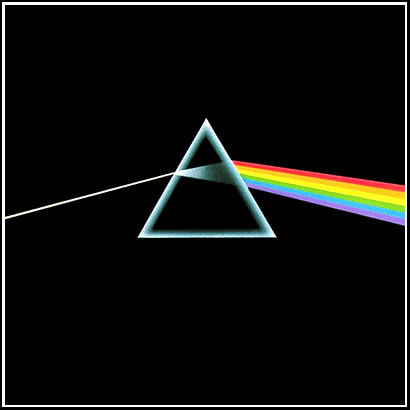

(The enigmatic cover of Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon.)

I threatened you that I was going to take you back to 1973. Fasten your seatbelt and turn up the iPod.

You have to put tunes to the year, that is the way it was. The Allman Brothers might have peaked that year, and Elvis might have made the first global concert a reality in his appearance in Hawaii, but the real deal was Pink Floyd, the elliptical English underground band that released “Dark Side of the Moon.” The album that stayed on the Billboard charts for a mind-boggling fifteen and a half years.

The Vietnam War, The Nixon Presidency, Jimmy Carter and the Reagan Revolution would all pass before the album fell off the charts. Of the class of ’73, Only Coleman Young outlasted the album.

That year was a tipping point in the history of the Motor City, and it was a privilege to be there for it, since I was part of the class of ’73, too. In that year, the Motor City demographics were at an uneasy balance. There was a scant majorty of white residents- 52%- with African Americans composing 44% and Latinos a bit less than 2% and the remainder a small but growing Middle Eastern community. Mayor Roman Gribbs presided, but he was a caretaker for the legacy of poor Jerry Cavenaugh, who took the rap for bungling the handling of the riots.

(The last- and only- Polish Mayor of Detroit, Roman Gribbs.)

Gribbs was determined not to stay on, not liking what he saw coming for the City, and that is just when I walked into the movie. There was going to be an election, a show-down between law and order and an entirely new order.

Just a little bit late. I had to finish up a couple credits in the first half of the bisected summer trimester term, and was just about ready to get out of a suddenly sleepy Ann Arbor in June. I cut my hair off and looked for work, and was surprised to find a job with the college textbook division of the massive McGraw-Hill publishing empire.

It was an unsettled time, just as Pink Floyd’s album talked of he madness in the air. I had a draft number that a couple years earlier would have had me casting about for a way to avoid being a rifleman in the war, but the last combat troops had been pulled out of Indochina in March of that year, and for the first time in a decade there was no pressure to find a deferment through grad school.

Not that Raven would have paid for it. That was the deal: I got a free education in exchange for a promise to not try to “find myself,” wherever it was I thought I might find myself.

The employment opportunity came courtesy of Raven’s network of friends, which was something I have always tried to remember. It also was a manifestation of the power of class taking care of itself.

Headquartered at 1221 Avenue of the Americas, McGraw’s tendrils reached first to St. Louis, and then through my reporting senior in Chicago. I was to cover a territory that rambled from Flint to Toledo, OH, but mostly covered the Wayne State-University of Detroit market, and the smaller colleges that existed then in the city.

Management knew the challenges of the traveling salesman well; the job title in fact was “college traveler.” My boss Dave knew the temptations inherent in continuing to live in Ann Arbor, and stipulated as a condition of employment that I live in Detroit.

Not having much alternative what with the uncertain economy laboring with the burden of Guns and Butter, I made plans to load my Chevy Vega mini-wagon with my belongings and move back to the City.

Porky was living at home then, between intermittent bouts of education in New Mexico. The end of the Draft was a godsend for him, since that enabled him to take a much more relaxed approach to formal education.

He suggested, successfully, that his parents Fleta and Jack rent me the empty maid’s quarters above the four-car garage of the mansion they had purchased on Afton Street. It was a spectacular residence, constructed in the 1930s in the Palmer Woods neighborhood just inside the city limits south of Eight Mile Road.

(The giant stove at the Fair Grounds. It was a wreck in 1973.)

Across the street was the Fair Grounds, where the gigantic wooden replica Garland Stove still stood to commemorate the old industry that had been supplanted by the automobile. It is one of the things that has been restored in the years since. Then, it was falling to pieces.

A Chaldean neighborhood sprawled south of there, and I can’t remember the name of the strip club directly across the boulevard, but it is long gone now.

Fleta and Jack, rest him, had made the bold decision to sell the pedestrian tract ranch house in Troy and move into the city. It was counter-intuitive at the time, since the city was unsettled, but the value of what they got in terms of the house was unreal. The place had been built to serve the needs of the owners of the Burton Abstract and Title Concern, and was a stone’s throw from the Dodge Brothers compound. The scions of the motor industry had created this little Oasis across Woodward Avenue from the Michigan State Fair Grounds.

Though the Barons were long gone for newer construction rout in Bloomfield Hills, the neighborhood was still upscale. Some white families hung on, reluctant to leave their old-school luxury; some newly-wealthy African Americans had moved in.

(Jack and Fleta’s place on Afton Street, Palmer Woods, Detroit.)

Soul Icon Smokey Robinson lived down the street, and the neighborhood association hired their own private security to keep out the riff-faff.

The value was extraordinary. There was the heavy brick and stone, laid in the English manner, with real ancient vines. Leaded windows, natch, butler’s pantry, attached greenhouse; walnut paneling throughout the main residence, and rosewood in my more humble two rooms up the narrow staircase from the garage.

Jack’s father Pop was living with them as well, and taking him in had been one factor in getting a place so big. I enjoyed watching the Watergate hearings with him as Dick Nixon’s presidency melted down, and on the whole, I was delighted with the situation. It was good to have some money of my own for the first time, and the rent was cheap and travel to the schools around town was opening up my eyes to all sorts of things.

Magical Woodward Avenue was right there, and that six-lane road of dreams was as familiar as the back of my hand. It was where we cruised on high-school weekends down past Mavericks to the Totem Pole Restaurant in the hot cars that our fathers brought home from the Car companies.

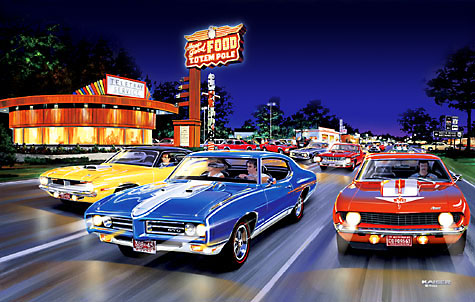

(“Woodwarding” with a Hemi ‘Cuda, Goat and Camaro, 1973. Print by automotive artist Bruce Kaiser.)

MoPars for Dick, the rich kid, who had race-tuned Charger RT’s and Hemis at his disposal. There were Pontiac GTOs, Olds 442s and all the Pony cars- Mustangs, Camaros and Firebirds. I was stuck with an AMC 343 Javelin, but the car would do over 120 miles an hour even if didn’t get there quite as fast as some of the others.

Part of that was the politics of the summer. I did not pay a lot of attention to it, and don’t think I ever changed my voter registration from Ann Arbor to participate in the mayoral election. I actually voted for Dick Nixon the year before, not that I cared much for the man, but I wasn’t alone.

Dick buried George McGovern in the fourth-largest majority in the history of Presidential Elections. I didn’t have enough invested in Detroit politics to care whether Police Chief John Nichols was going to beat firebrand activist and state senator and insurance salesman Coleman A. Young.

LA had had Bill Parker, the ironclad police chief from 1950 until his death in 1966. He turned a corrupt, demoralized force into a feared paramilitary unit. Philly had Frank Rizzo, the self-styled “toughest cop in America” who went on to become it best-known police chief and later mayor of the City of Brotherly Love.

The Motor City had Big John Nichols. He was a bull-necked crew cut, blunt-spoken police chief who brooked no nonsense from criminals with his Tactical Units and STRESS, the acronym referring to “Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets.”

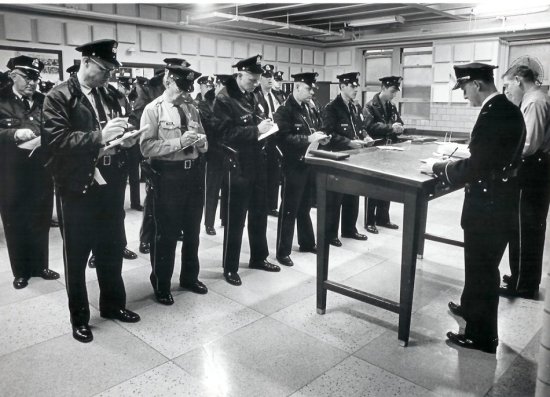

(Police Roll Call 1973.)

Roman Gribbs was the first (and only) Polish mayor in Detroit’s history. Big John Nichols was his chief of police, who was picked by the powers that be to succeed Gribbs. Nichols was one of the few city officials whose reputation was enhanced when he called for his calls for a strong police presence to crush the rioters.

The Unit was famous for shooting first and asking questions later. One of their favorite tactics was the classic set up. A decoy officer would be placed in a high crime area- the prototype for what NYPD Chief Bill Bratton called “CompStat”- and then conceal the tactical team around them.

When a mugging occurred, the officers would appear. The mugger, almost always black, had the choice of surrender, flight or fight. In the latter options, twenty young men were shot to death. There was tremendous support for the unit in the white community, and tremendous resentment about it in the black community.

Opposing Nichols was State Senator and community activist Coleman A. Young. Promising that he would disband STRESS, he proposed to put more cops on the beat and to set up mini-police stations in fifty different neighborhoods. Both men offered a variety of proposals for improved housing and transportation, but the issue was safety and why no one felt that way, black or white.

It was inevitable that there would be an African American mayor in Detroit, just as it was inevitable that a mostly white police force was going to have major problems. It was just a question of whether it was sooner, or later.

One issue that was far beyond the city limits at Eight Mile caused a little discussion in October of that year. Syria and Egypt attacked Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The rattled IDF experienced strategic surprise and the worst battlefield losses in its short history.

Prime Minister Golda Meir offered to fly to Washington to personally plead with President Nixon to resupply Israel.

(M-60 Tank rolls off a USAF C-5 Galaxy transport as part of Operation NICKLE GRASS- the emergency resupply of IDF equipment.)

The promise came from the White House, and was announced by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: “The president has agreed, and let me repeat this formally, that all your aircraft and tank losses will be replaced.”

That was in early October of 1973. On October 16, 1973, the ministers of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries announced a decision to raise the posted price of oil by 70%, to $5.11 a barrel.

In early November, Coleman A. Young beat Big John Nichols by 15,000 votes to become the first African American Mayor of a major American city. In the middle of the same month, Dick Nixon announced that he was going to hit the brakes on the hot rods of Detroit- he was going to impose a 55 MPH speed limit.

(Mayor-Elect Young, 06 November 1973.)

Coleman Young immediately disbanded the STRESS unit, and issued a warning: “To all those pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers: It’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road! And I don’t give a damn if they are black or white, or if they wear Superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges. Hit the road.”

In a way, all of us complied. White Detroit just hit the road a lot slower than it would have before the gas prices went up. The whole thing was going to affect the city like a trip to the back of the moon.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Southern Strategy

(The lower 9th Ward of New Orleans, five years after Katrina.)

So, the morning jig through the very strange year of 1973 in the Motor City was interrupted by a call from my Coon-Ass buddy, Boats.

He was up early to head to his current position as a moderately senior Government employee involved in Homeland Security. He took umbrage with my contention that the urban centers of America were all burned down in the rage that followed the assassination of Dr. King in 1968.

He was on a tear, I will tell you. But I need to give you some context on what he said first.

Boats is a life-long federal officer, currently geo-baching it in the National Capital Region trying to nail down his “high three” pay years to calculate his retirement.

Boats is a Southern Man, through and through. He is proud to be a Master Chief Bo’sun’s Mate, and equally proud of his status as a coon-ass Louisiana native. He normally lives in the Crescent City of New Orleans, and the winters up here make him a tad cranky. I don’t blame him. We were supposed to get some sleet last night, and the winter is hanging on like grim death into April.

I don’t think he takes any pleasure in the fact that more people have been displaced from my birth city of Detroit in the last decade than had to flee the destruction of Hurricane Katrina in his.

There was a lot of coverage of the spectacular destruction of the Lower Ninth Ward, and the exodus of the residence after the levees failed. People are coming back, though, and the city is back to about 80% of the population it had before the storm.

(Arial photo of the neighborhood around St. Cyril Cathedral near Haper and Van Dyke, 1949.)

Detroit, by way of contrast, has two thirds of the total population of the Big Easy and has sufficient abandoned lots to cover the entire city of San Francisco. The more than hundred square miles that compose the Motor City proper are divided between expanses of decay and eerie emptiness between tracts of still-functioning communities and commercial areas. “Urban Prairie” is the current term of art for the swaths of vacant property growing up in waist-high grass.

(The same neighborhood as an urban prairie in 2003.)

“You wrote that all the other central cities in the nation were torched,” said Boats, without much in the way of pleasantries.

“Yeah,” I said, with a little apprehension. “Sure seemed like it at the time.”

“Well, for the record, Buddy, the cities of New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Mobile, Houston, and most of the big cities from Georgia to Texas did not burn, or for that matter even experience riots.”

I held the cell phone to my ear, wondering if that was true. It certainly seemed like everything was on fire that season, but maybe it was because I was living next to the Big Tinderbox east of 8 Mile.

“Contrary to the northern press musings it wasn’t because these cities had more draconian controls over the black population. Looking back,” said Boats a little less forcefully, “I think it was simply a case of proportion and proximity. While we had experienced formal legal segregation, in fact, there were so many of us living in close proximity that whites in these southern cities may not have moved in the same social circles with blacks but everyone personally knew and interacted with people of the opposite race that they liked and respected.”

“That certainly was not the case in Detroit. We were separated by the wide swath of 8 Mile and seven more miles in Grabbingham,” I said.

“Down south, we knew we were different from each other but neither of us thought of the other as alien. Even with formal segregation we weren’t as segregated of a society as the northern and Los Angeles “ghettos”. It would have been hard to identify a “ghetto” in these southern cities that tasted sit-ins, and protests, but not riots and looting and burning.”

I nodded to no one in particular.

“When the big change finally came,” Boats continued, “we didn’t have as big a gulf of mistrust and bitterness to overcome. The South isn’t proud of its history of race relations but we actually had relations, not isolation.”

“The latest census indicates that African-Americans are fleeing the cities and moving to the suburbs. There is even a significant reverse migration down south,” I said. “That was pretty surprising.”

“It would only be surprising to you Northerners. Strained relations can be repaired. Isolation must be “overcome” and it will be violently overcome if it is easy to dehumanize your adversary and it is easy to do so if you have no contact.”

“There wasn’t any diversity in Grabbingham,” I said. “Though I have to say that Detroit has the largest Mideast populations in the West. The Chaldean and Iraqi communities are huge.”

“Well,” Boats responded, “In the South we have always known each other, and we have not been universal in our likes and dislikes on either side. The bottom line of history, I think, is that the riots of the North and California were not neighbor-against-neighbor conflicts but an expression of anger by one group against another that they didn’t know and saw universally as oppressors. In New Orleans, if it had happened it really would have been neighbor against neighbor; and before it happened, we really looked at each other and decided that nothing was worth that.”

“The violence in Detroit was oriented against business, and then in the years of the crack epidemic it was directed against the community itself.”

“Yep. What is it about “Yankee” culture that causes it to look south always with thoughts of what “corrections” our region needs? Why do you always think that we need “instruction?”

“I dunno, Boats. I had not thought about it that way. It is like what the Canadians say about the US Border: it is the longest one-way mirror in the world.”

“Yep. You see only a reflection of yourself. You say Detroit is dead?” Declared Boats. “If you want to see where America makes cars drive through Georgia southwest from Atlanta towards Birmingham, AL. You won’t see a big city with car plants you’ll see big plants set in among cow pastures and soybean fields with full parking lots of workers who commute from rural communities in a twenty mile radius.”

“It was the companies getting out from under the Unions,” I said. “It destroyed the working middle class that could afford the cars they built.”

“Take it further. You say the family farm is dead? Take a look at rural Louisiana, East Texas, Mississippi and parts of Tennessee. Very conventional family farms dot the landscape peopled by young families. The male of the household has a job that requires travel and long periods away from home followed by long periods free of any daily employer imposed grind.”

“Typical employment includes working the off shore oil rigs, crewing the tows on the Mississippi, and over the road truck driving, all relatively high wage hard work for high school graduates. The father on those farms, black and white, puts part of his income into the family farm. In those poor years when it doesn’t make a nice profit serves as a tax shelter from the overreach of Uncle Sam.”

“There is an aspect of Northern urban government that raised taxes as the revenue base shrunk. It crushed everything. No business could make a profit and survive. Everything imploded.”

“You got it. Our suburbs and college towns are quietly filling with retirees, our country side is not abandoned. Yet our resistance to all those federal policies that caused the northern family farm to be sold out to corporate farmers, and the countryside to be abandoned, and the city centers to generate ghettos is met with utter contempt.”

“I can’t quite get over the resentment of what happened, and it all turned on the back of labor and ace,” I said. “Chicago lived, and Detroit died.”

“Lets be real about the history of the sixties” said Boats quietly. “Segregation had to be ended in the South and it came with some pain and even death. But it came without riots and burning of cities. Those events were peculiar to a different culture from us, with its own set of racial problems that were unique to that region.”

“Segregation continued right up to this last decade in the North,” I said thoughtfully. “But it was de facto, not de jure.”

“And it still does. Southerners white and black did not cause the northern riots, looting, and burnings. Southern whites burned some crosses and a couple of churches and murdered about a dozen people before racial relative peace was restored in the South and segregation was deconstructed.”

“What happened elsewhere in the country during that era may have traced its earliest origins to the out migration of blacks from the South at the end of the Civil War, but there was no southern-based conspiracy that ignited those riots. The riots were the local reaction to local conditions, It was a stranger-on-stranger war.

“We had some murders among family and decided to make peace. We are progressing today. In the thirteen states of the Old South there is no “rust belt”. The Klan is all but dead. Our big battles today are keeping what we have built from being ruined by the same short sighted tax-spend-social engineer and dictate policies that originate in places like Massachusetts and then become law and policy in Washington.”

“If the South could form a new confederacy today it would be a peaceful and prosperous, financially responsible, middle power. What would be left would be a bickering, rusting, interventionist, bankrupt superpower wanna-be headed for collapse.”

“Ouch,” I said. “That is sort of a harsh assessment.”

“It is, but true. The South, never looked to for wisdom, is today the brakes on the train wreck that our Yankee-led nation has become.”

“It is a little bit of a stretch to call a Chicago Progressive Administration a bunch of Yankees.”

“I am only using the term as we speak it down South. By the way,” Boats said. “In-southern speak “Yankee” does not include areas south or mostly south of the Mason Dixon line like Maryland, Delaware, or Kentucky, nor most of the Midwest, west of Illinois, or the Mountain West, but it definitely includes the “Left Coast.”

“Yeah, and with California projecting a twenty billion dollar annual budget shortfall that has got to change.”

“The South will not rise again, it has risen but is dragging the dead weight of an alien culture, one that I’ve now seen up close and personal in Washington DC. It will slow the descent of that culture but the dead weight is too much. We will sink with the Yankees unless we find a way to regionalize and compartmentalize our gains without wasting energy and resources on another war of succession.”

“Is that what all that neo-nullification state legislation has been part of?”

“That is my view,” said Boats firmly. “Next, look for a wave of ineffective mitigation barriers to try to keep the alien culture from doing to the rest of South what it has done to Florida. The union can and will be broken not by states trying to exit, by the natural results of its own political and budgetary foolishness.”

“Once its back is broken, it will be in no position to stop the independent rise of any former region poised to prosper. Rome fell, it is deader than a stone. But Italy is a nice place today. That is how we are thinking in the modern South today.”

“Copperheads should start carving out a place for themselves among us while there is space remaining in the life boats. We will not preach or try to impose our values on the Yankees. The tendency to impose outside solutions on alien cultures is a Yankee cultural trademark, not ours. We are busy caulking our region for the flood to come. After we survive the flood we will concentrate on rebuilding prosperity and peace under a model that would be familiar to Washington and Jefferson, but alien to Hamilton.”

“If all of American history is the rattling of the chains of the ghosts of Hamilton and Jefferson the truth is the South never liked that little elitist prick Hamilton. When he is done running amok among the Yankees, we are going to permanently lock him out of the South.”

“That is a lot to plow through, Boats,” I said, wondering if this was a north-south problem, or a red and blue one.

“In the immortal words of Texas’s Judge Roy Bean: “and that’s the way it was, and if it wasn’t like that…that’s the way it shoulda been.” I might add, gonna be.”

“I gotta think about this, Boats, but thanks. I have been wondering how to parse the great divide between the Tea Party and the progressives. The gulf is so vast that the government seems to have become completely dysfunctional.”

“Yep,” he said. “But I have to go. The dysfunction hasn’t got to my cubical yet. But we may all get furloughed next week when the Government shuts down.”

“We did not get to the fact that this is going to be an America that speaks Spanish pretty soon,” I said. “And that is going to take a little getting used to.”

“Trust me, when you have been occupied by an invading army, you figure things out pretty quickly. Adios, Amigo,” said Boats, and broke the connection.

Copyright Boats and Vic 2011

www.vicsocotra.com