Editor’s Note: Here at Socotra House, we passed a significant milestone on Friday of last week. I had grown weary of toggling through a 600-odd page manuscript. It was time to whack it into more manageable chunks. I broke it chronologically into the Pacific War years of RADM Donald “Mac” Showers, then his time in the age of Hot & Cold Running Wars, and finally his time at Langley and retirement to become a mentor and care-giver. He was superb at them all. Now it is time to print a hard-copy of the thing and do a close edit and see where we go from here. This chapter from the book is from one of the earlier interviews we did, and provides a sort of road-map to the astonishing careers he had. I will keep you posted on the continuing journey about a good friend who saw some extraordinary things.

– Vic

This was at the beginning of my decade-long friendship with Mac, and just at the time we started to take on the project of looking at his amazing life with an eye to telling the story.

It had been a strange day in Arlington, though things are strange enough in Washington that only the addition of nuclear weapons could really give it some pizzazz. The Nuclear Conference wrapped up downtown at the convention center. First Lady Michele Obama made a dramatic appearance in devastated Port au Prince. The talking heads are speculating on the impact of the retirement of Associate Justice John Paul Stevens from the high court.

Mac and I got seats half-way down the Willow’s bar, being just a bit ahead of the rush. The place is quite fashionable these days, and maybe it is a sign the Recession is fading. It was mild in impact around here, though it is hard to say if the people drinking exotic vintages ever noticed it much.

I asked him about Justice Stevens, and remarkably, it turned out he was a wartime colleague in Hawaii. I asked about his involvement in the shoot-down of Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, which featured prominently in the published biography.

“OPERATION VENGEANCE,” Mac said, nodding, “and it was a long-range intercept of the Admiral’s personal aircraft. The mission was based on intelligence derived from decrypted Japanese communications that outlined the itinerary for the Admiral’s inspection trip to several bases in the Solomon Islands on April 18, 1943. Army Air Corps P-38s operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal successfully shot him down.”

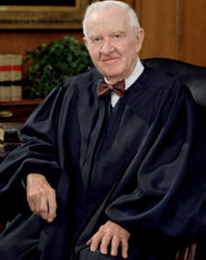

(Associate Justice John Paul Stevens. Mac used to dine with him at lunch the O Club near the Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Makalapa Crater).

“It was a terrible blow to the morale of the Japanese Fleet,” said the Admiral, “once they had to admit it happened. They kept it secret for a while.”

Justice Steven’s bio notes his contributions to the effort, though Mac doesn’t remember it quite that way, and he is almost the last one in a position to know. He was a Lieutenant with Stevens, who he remembers as a polished lawyer and gentleman from Chicago. They were in the same unit at Pearl during the war, and often had lunch at the bar at the club attached to the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters.

Admiral Mac is approaching his 91st summer in this world, and is still chugging merrily along. He broke his elbow in a fall a month or so ago, which resulted in surgery and a marked diminution of his communications, since he was reduced to one-handed typing.

He does not drink any more, on orders from his oncologist, though he doesn’t mind watching. He enjoys a Virgin Mary with olives and lime and horseradish, or just a ginger ale. We had begun to meet to talk about the events of his distinguished and highly secret career, since most of the great events may still remain classified but are hardly a threat to anyone left alive.

I picked him up in the covered circle at the front door to The Madison high-rise assisted living facility where he lives, and we drove across the street to the Willow.

“Stevens was a good man,” said Mac. “Though I have to say the modern story of his involvement in the Intelligence Community is a little overblown. I know something about that, since I helped establish the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Courts later in the 1970s.”

Mac went to say that Stevens might have been recruited to be an Air Intelligence Officer rather than a cloak-and-dagger Spook like the published biography implies.

Mac looked thoughtful as he recalled and I dodged pedestrians to try to get parking at the curb directly in front of the door to the bar.

“Admiral Forrest Sherman created the whole air intelligence program,” he said. “Sherman believed that the perfect AI was a lawyer by training, and he was right. They know how to listen, take depositions, and speak succinctly in a briefing. Admiral Forrest Sherman wanted orderly legal minds to take care of his cadre wearing the Wings of Gold. That is probably why they approached John Paul. I don’t recall him being around in early 1943, but it is possible.”

“It is probably why they all got out at the end of the war to go back to lawyering,” I said with a laugh.

(Fleet Admiral Yamamoto)

“You might be right. LT Stevens was a new guy when I was there, and I had literally months of experience. I had reported to the code-breaking unit at Pearl (Station HYPO) in February of 1942 when the ships were still on the bottom of the harbor. That unit’s unclassified name was the Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC) and was already humming when Mac arrived in February 1942.

Mac hadn’t mentioned the dumb luck of it all. I started jotting notes on bar napkins, which surround me now. Long story short, he had never been ‘destined’ for anything like the illustrious career he had. It was completely by chance that he was selected to go to the six-week Investigations Course at Seattle after commissioning on 12 September of 1941.

The 90-wonder course in Chicago was intended to produce Deck Officers for the growing Fleet, and it was complete chance he did not get orders to a ship, as most did. Some of them had enough time after commissioning to arrive at their first duty stations in Hawaii to die under the Japanese bombs.

The December 7th attack happened just after he completed the investigations course; he served briefly in the Public Affairs office in Seattle. His duties included resettling Alaskan families in the Pacific Northwest, due to the threat of war. And then it began in earnest.

All the Ensigns immediately were given orders west, toward the crisis. Half were assigned to the 16th Naval District in Manila, the other half to the 14th ND in Honolulu. Dumb luck, or it could have been the alphabetic order in which they were issued.

“Showers” fell in the second tranche of orders, and he was headed for Honolulu.

The 16th Naval District was in Manila. The kids who got those orders took the train down the coast to the Sea Port of Embarkation (SPOE) at San Francisco to the Philippines, and arrived just in time to proceed directly from the docks at Manila into Japanese prison camps- the hellholes of the South China Sea.

Some of them lived. Just Dumb Luck that Mac did not have to endure the horrors.

Mac instead got orders to the 14th Naval district in Honolulu. There was no Waikiki in those days; that was just a swamp west of Downtown and the Aloha Tower and the Matson passenger terminal. He was billeted in the YMCA near Hotel Street and the Aloha Tower where the Matson Liners landed.

The day after arrival, he walked in the soft breeze amid the scent of flowers from the ‘Y’ to report to the District Intelligence Officer as ordered.

The District Intelligence Office was in a hotel the Navy had requisitioned to accommodate wartime needs, and Mac was startled to note that the Assistant DIO who received him wore two pearl-handled pistols on his belt due to his perceived threat of domestic Japanese terrorists.

“The guy was a regular Cowboy,” said Mac. “He got right to the point, too. He asked me how much field investigation experience I had. I told him I had successfully completed the six-week course in Seattle, but otherwise had none. The Cowboy positively fumed.” Mac chuckled, remembering the interview. “It was a guy named CDR Pease, and he was the Deputy in charge of counterintelligence, among other things.

“So, the Cowboy kind of sneered at me, saying “I need men with experience, and you are worthless to me.” Mac said he rocked back in his chair and the pearl handles of the pistol poked out. “He said he had a billet out at the Shipyard he had not been able to fill since he needed all the experienced help downtown. Then he said he had just found someone he didn’t need.”

Next morning, Mac had orders to the Shipyard, and found Station Hypo in the basement of the Administration Building, near the bustle of the recovery efforts to salvage the stricken ships that leaned crazily at the piers or had capsized at their berths in the harbor.

By noon, Mac found himself reporting to a Navy Commander named Joe Rochefort, one of the small handful of men who understood radio, codes and the Japanese language and culture. His little unit made critical breakthroughs on the Japanese JN- 25 code system, but it came at a cost.

Mac was put to work immediately, experience or no. There was a war on, after all. As mid-1942 approached, FRUPAC was literally under the gun. There were periods of round- the-clock work on intercepted messages.

(Charleton Heston (l) and Hal Holbrook as Joe Rochefort (r) in the 1976 film “Midway”).

“Did Commander Rochefort work in his bathrobe, showing up for briefings at the CINCPACFLT HQ up at Makalapa Crater late and disheveled, like actor Hal Holbrook played him in the movie “Midway?””

“We did what we had to do in The Dungeon,” replied Mac. “But do not make the mistake of thinking that Joe Rochefort was anything like the crypto-mystic Holbrook made him out to be. Joe was a pro.”

I kept writing on the growing pile of napkins in front of me. Mac sipped ginger ale and told me he had been working there about three months when the frantic effort climaxed with the decryption of just enough JN-25 traffic to understand the objective of the Japanese attack.

Washington thought the Japanese were headed for Alaska, having detected the movement of a diversionary force intended attack American interest away from the actual objective. Washington had it wrong, and that was going to be the basis of animosity and jealously that would last decades.

If you had not heard, Washington hates to be wrong.

The main body of the Japanese Navy was going to strike and seize Midway Island, and establish a bastion from which they could threaten the Hawaiian Islands.

Rochefort, with Fleet Intelligence Officer Edwin Layton, convinced Admiral Nimitz that Midway Island was the real objective. In an act of serene confidence, the Admiral gambled on the ambush that resulted in the Battle of Midway, 4-7 June, 1942. In the fight, the Japanese lost four carriers and most of their skilled naval aviators.

It was the turning point of the Pacific War.

Mac eventually transferred from FRUPAC to be Eddie Layton’s assistant, and to deploy forward to Admiral Nimitz’ forward HQ at Guam. He worked as chief of the forward Estimates Section on what would happen with the land invasion of the Home Islands, that helped make the decision to debut the use of the (atomic) Gadgets against Japan.

Five days after the surrender, with the help of his Boss CAPT Layton, Mac made a visit to Yokosuka Naval Base, from which the Imperial Navy ships had departed to strike Pearl four years before.

He was awarded the Bronze Star for his work with the code breakers. It was all just dumb luck that he was not in the half of his class that reported direct to be prisoners of the Japanese.

LT John Paul Stevens, USNR, finished up his time at FRUPAC, which had moved from the basement at the shipyard to the temporary building in back of the PACFLT Headquarters. He demobilized and got on with his life as a lawyer. As it turns out, he did pretty well.

Mac stayed in the Navy, of course, and joined the people at Langley after he retired, and then retired again, and is busier in the third part of his life’s work than he ever was.

(Justice John Paul Stevens on the High Court).

He is still occasionally in touch with his old wartime buddy, and told me when I dropped him off at The Madison that he would ask him how he was planning on enjoying his retirement.

I smiled and was already compiling another list of questions. This had been a stratosphere-level. Now, we could come back and get into the weeds. I said: “We need to get together again soon, if you would be willing.”

“I would be happy to,” said Mac.

“I have some follow-on questions, Sir, and I want to ask them one at a time, rather than a whole war in just a few drinks. Or ginger ales, as the case might be. The one I will leave you with is this: was it all just dumb luck?”

“You don’t know the half of it, Vic,” said Mac. “I would be happy to continue to get together. There are a couple things I would like to get straight, while there is still time.”

Then he turned and walked briskly into the lobby of the Madison, his posture perfect, except for the slight list from the weight of the cast on his arm.

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocora.com