Major General Lew Wallace, his division, and my Great-great Grandfather stopped at Crump’s Landing to destroy the tracks of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. It was one of the things armies did in those days, and I am interested to discover that my ancestors specialized (in appropriate context) the mass destruction of railroad rolling stock and tracks.

It sort of makes you swell with pride, you know?

Anyway, the 72nd OVI was with Major General Wallace because that is what the table of organization said: Fourth Brigade of the First Division of the Tennessee Army under William Tecumseh Sherman. They had marched out from Camp Chase, Ohio, in January and then on to Paducah, KY. From Paducah they were told to advance to Savannah, Tenn., in the first week of March.

It is 155 miles to go the distance- on foot. I won’t bother you with the mileage on every movement, but you get the drift. Consider for a moment that you are wearing a Federal-issue heavy wool jacket and trousers. The nature of the War in the West means you are carrying what you need, and in addition to rifle and ammunition, there is hard tack and bacon and beans to be carried.

Think of the humidity in the places they were marching, hay-foot, straw-foot, mile after mile. From Savannah, they marched 20 miles to participate in The Expedition to Yellow Creek, Miss., and then the occupation of Pittsburg Landing, TN, 15 miles to the north the next week.

That was the reason they were in Crump’s Landing on the 4th of April- to commit some vandalism of the South’s railroad lines.

These stories are not intended to be a version of the ‘Great Man’ theory of history. I despise revisionist historian Howard Zinn, by the way, and am only trying to get to the experience of a young Irish teamster through the lives of the notables. Grandfather left no personal record of his experience in the great Civil War, but these were the events that swept him along.

I must say, trying to get to him, I keep bumping into men who either seized greatness, or had ignominy thrust upon them. There had never quite been anything quite like what was happening in North America in 1862- and with luck, we will never see anything like it again.

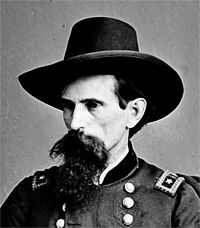

Lew Wallace is one of those amazing fellows, a truly remarkable man, and more than the sum of his parts. He was a known attorney, son of an Indiana Governor, Union General, Governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat and novelist, whose most famous work was the historical adventure story “Ben-Hur: A tale of the Christ.”

Some have called the 1880 best-seller the “the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century.” I don’t know about that- there has been a lot of water over the dam since that century ended. I have put it on the list for reading some time in the future, but I did see the movie with Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur, and that is going to have to be good enough for the purposes of why Wallace was at Crump’s Landing, an otherwise undistinguished landing on the verdant shores of the Tennessee River.

Wallace was not a West Point man, like so many of the figures who loom large in this chapter of our common history. Or uncommon, as it may be.

Lew’s father had attended the Academy, though, and he was favorably disposed to uniformed service. When the Mexican War came along in 1848, he volunteered, returning to civilian life when it was done.

He established a legal practice back in Indiana, and when the war clouds loomed he accepted an appointment as Indiana’s adjutant general and command of the 11th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He was at Fort Donelson, where Uncle Patrick was captured the first time, and his performance there earned him a promotion to major general. At the ripe old age of 34, he was the youngest MG in the Union Army.

If you want to look at great favor generating hubris, I suppose you can make the case. But what was going to happen at Pittsburg Landing was going to swamp anything that had happened on this continent before, and scapegoats would be necessary.

Lew’s force was left to conduct his anti-infrastructure task by Grant, who ordered the Army of the Tennessee (still known then as the Army of West Tennessee) to move to Pittsburg Landing four miles upstream.

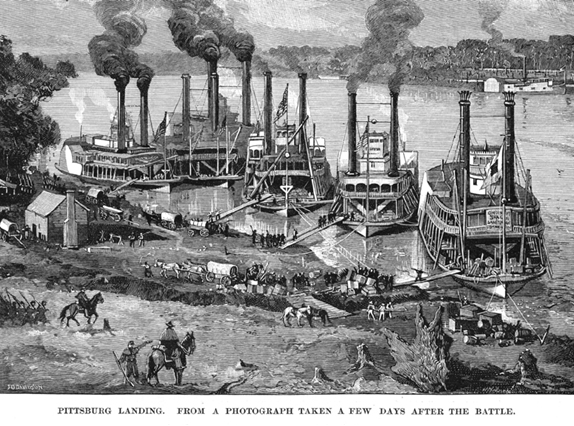

As a retired sailor, I find it of interest that this was an amphibious campaign, with command moving by steamship along the River. Lew Wallace had a boat- the John T. Roe. Grant had one as well- the Tigress- and this is the image of the Union Headquarters ships at the landing a few days after the biggest battle that had ever occurred in the Americas.

They got better at the art of slaughter, but this event was electric in the press descriptions of the scope and savagery involved.

But let’s go back to why scapegoats would be needed, and what Lew Wallace did to become one. On independent duty, Wallace had his cavalry destroy railroad tracks unopposed, but ran into resistance on the stagecoach road between Crumps and the hamlet of Adamsville.

Wallace decided to bivouac two brigades along the road between Crumps and Adamsville, and kept a brigade near his command vessel in the river. His Third Division engaged Rebels in several skirmishes, and for defensive purposes, directed his troops to began improving the road known as the Shunpike. The pike headed south from Stoney Lonesome, a picturesque name for small group of cabins on the stage road. The Shunpike ended at the Hamburg-Purdy Road, to the west of William Tecumseh Sherman’s Headquarters.

Opposing Grant was Albert Sidney Johnson with a force of nearly 50,000 Rebel troops. When he arrived at Corinth, MS, in late March, he ordered Major General Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Cheatham to advance to Bethel Station to prevent further Union raids.

Utilizing the ISR assets of his day- cavalry, mostly, along with snitches, spies and captives- he discerned that Wallace was detached from Grant’s main body. Grant was also waiting for the arrival When he arrived, Cheatham informed Johnston that he was facing Lew Wallace’s division and that it appeared to be detached from Grant’s main force. Johnston knew the Union plan was for General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio to arrive and combine with the Army of the Tennessee to create an overwhelming force that would drive all before it.

Accordingly, Johnson decided to preempt and attack before the Union armies joined. Johnson was his own intelligence officer, and estimated that with Wallace detached, Grant had only 37,000 troops and he had the edge. Fortune favors the bold, I am told, and though he would not survive the fight he was about to start, Johnson was a bold son of a gun.

At dawn on April 6, 1862 almost 50,000 Confederates hit Sherman and Benjamin Prentiss at Shiloh, driving them back towards Pittsburg Landing. Wallace was awakened in his cabin on the command ship about 6:00am by an orderly. The sound of guns was apparent, and not far away. My grandfather’s horses would have become alert at the sounds, their ears twitching in alarm at what they would be asked to do.

Lew Wallace chose to concentrate his forces at Stoney Lonesome rather than Crump’s Landing because of the improvement his men had made to the Shunpike. Taking it south would be much easier than traveling the alternate route on the River Road, which had suffered heavily from recent heavy rains and the tread of thousands of feet and hooves.

Travelling south from Savannah, Tennessee, in his command ship, Grant met Wallace in the mid-channel of the Tennessee River. He directed Wallace to be ready to move out on command, but to stand firm for the moment. The Confederates had no presence on the river, and Wallace left the landing at Crumps with only a few sentries. Since the Union line of communication was on the water, he left a horse so that a courier could reach him at Stoney Lonesome if orders from Grant arrived.

Grant continued upstream to Pittsburg Landing, arriving about 0900. It didn’t take rocket science to know his forces were outgunned, and he issued orders for Wallace to move out and reinforce Sherman on the Union right. An aide scrawled the orders and dispatched a courier by boat to Crump’s Landing. From Crump’s, the courier rode to Stoney Lonesome and gave the order to Wallace, probably about 11:30 am.

And what Wallace did then colored the rest of his life, literary fame notwithstanding. He took Grandfather and the horses along with him, and therein lies the tale

(The site of Stoney Lonesome today. Wallace ordered his troops to take the curve to the right. The turn to the left would have taken him to the River Road. Ah, the road not taken…..)

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

twitter: @jayare303