(John Singleton Mosby. Image Library of Congress)

There is one thing worth mentioning about Marshall, VA. Well, maybe two. I was last there with a pal looking for real estate in horse country. It didn’t work, but we saw a lot of places with decimal points in the asking price. But it was horsey, all right, and in the heart of Mosby Heritage Country. Marshall is also home to the oldest continually operating Ford automobile dealership in the US; it has been in the same building since 1915.

The other thing of interest involves The Gray Ghost, guerrilla Confederate cavalry officer John Singleton Mosby. The times shape the man, they say, and that was true enough of him. There is a historical society that minds the memory of his exploits in Northern Virginia during the Late Unpleasantness Between the States: The Mosby Heritage Area Association.

The Association’s mission is “Preservation through Education – to educate about the history and advocate for the preservation of the extraordinary history, culture and scenery in the Northern Virginia Piedmont for future generations to enjoy.”

You can sense that they had stepped a bit away from the celebration of the Lost Cause and are now concentrating more on the landscape and the historic buildings and relics that remain.

They are a nice bunch of people, and they hold programs at some of the sites that were associated with the incredible number of armed actions of the Civil War. They say that Culpeper County was the most fought over, all told, but Mosby patrolled a little to the north in Loudoun, Fauquier, Clarke, Warren, and the western tip of Prince William Counties.

It is no coincidence that those jurisdictions compose the heart of Virginia Hunt Country, which is what brought us that day to Marshall in northwest Fauquier.

Mosby is an unlikely fellow to have his own historical area. He was born in 1833 in Powhatan County. He was a puny kid, often sick, accordingly a target for bullies at school. Despite it, he developed exceptional self-confidence, and learned to fight back against his tormentors. It is sort of an interesting concept in this age of anonymous cyber-bullying. Then, one had to put your dukes. Or more.

After he completed primary studies, he went on to attend Mr. Jefferson’s school (the University of Virginia) where he studied the classics. He ran into more bullies, though . D uring a confrontation with one of them, Mosby pulled a pistol and shot his adversary in the neck. Apparently it was not fatal, though Mosby was arrested, sentenced to a year in jail, and issued a $500 fine. UVA also gave him the heave-ho.

That would be discouraging for many of us, but the times were different. The Governor granted a pardon on the grounds of ill health in early 1854. While incarcerated, he had struck up an acquaintance with the local DA, who allowed him to read his law library. After he was sprung, he continued to read the law and was admitted to the Virginia Bar in the same year.

He settled in Howardsville, Virginia, south of Charlottesville, where he met and married his wife Pauline. They had three children.

In 1861, Mosby maintained a Unionist position, as did many Virginians. Waterford in Loudoun County even raised two companies of Cavalry to serve in the Union Army. But like Robert Lee, as hostilities loomed Mosby chose his State over his Country.

Mosby was an excellent horseman and enlisted as a private soldier in the “Virginia Volunteers,” a company of mounted infantry. He saw action at First Manassas, and came to the attention of the Grand Cavalier, J.E.B. Stuart.

Assigned to Stuart’s cavalry scouts, he gained his commission and was once captured and saw jail time again in the Old Capitol Prison in the District before being paroled. That was a common practice back in the day, one that Great-Great Uncle Patrick Griffin shared after being scooped up by the Yankees after the action against U.S. Grant early in the war at Fort Donelson.

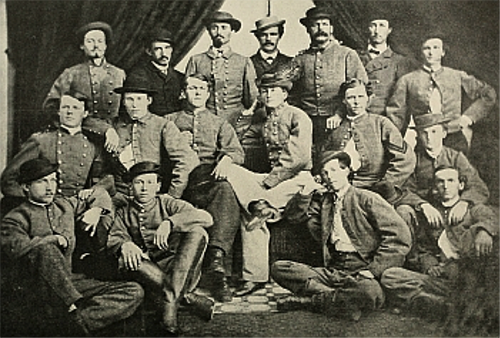

(Mosby’s Rangers. Mosby is seated in the center. Image courtesy of Francis T. Miller)

In January of 1863, Mosby was back in Rebel ranks and in winter camp in Culpeper. Stuart promoted him to Major and placed him in command of the 43rd Virginia Cavalry. His orders were to conduct guerilla warfare, and raid and harass Union Forces operating in Northern Virginia and out to the Shenandoah Valley.

“Mosby’s Rangers” immediately got to work, and the fame of the unit grew with each success. Due to his skill at evading Federal pursuit and the tacit support of the Virginia populace, he was subbed “The Gray Ghost” by the newspapers of both sides.

The site of his most famous raid was not far from the place I used to live in the suburban wasteland of Fairfax County. In March of 1863 he was behind Union lines and hit the old Fairfax County Courthouse on Ox Road. He found the Federals unready. Mosby found Union Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton sleeping soundly. He awakened him with a brisk slap n the buttocks.

“Do you know Mosby, General?” he asked.

The General groggily replied “Yes! Have you got the rascal?”

“No,” said Mosby. “He’s got you!”

Naturally, the guerrilla war was conducted unconventionally. Mosby’s Rangers jousted with Phil Sheridan’s forces through 1864, and the plucky Union general became increasingly frustrated in his attempts to stop the raids and neutralize the Rangers. Prisoners were executed out of hand. Federal forces hung six Rangers in Front Royal and a seventh captured in Rappahannock.

In response, Mosby’s men did the same, with the sanction of the chain of command. Twenty-seven Union prisoners were selected at Rectortown- I read the historical marker there in amazement one sunny afternoon a few years ago. The prisoners were ordered to take part in a lottery to determine which seven of them would be killed. One of them who “won” on the first round was a drummer boy, just a lad. Mosby could not abide the death of one so young and let him go, but he made the prisoners take another turn to find a replacement. In the end, only three Yankees were killed.

Mosby found the matter distasteful and finally wrote General Sheridan in November requesting “a mutual end to the brutality” and Sheridan agreed.

(Mosby’s Rangers on a raid in the Shenandoah Valley. Image from James E. Taylor)

In the Spring of 1865, Mosby’s Rangers continued raiding behind the Federal lines even as Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia fell back from Petersburg and eventually was cut off and surrounded at Appomattox Court House, where Lee surrendered 150 years ago last week on April 9th.

Now a Colonel, and with a significant bounty on his head, Mosby decided not to surrender but rather disband his command and let his Raiders return to civilian life. He had the 43rd Battalion, 1st Virginia Cavalry, line up on horseback in parade formation in Marshall, VA, on the morning of 21 April.

Eyes moist, he produced a paper from the inner pocket of his service blouse and read these words:

Soldiers! I have summoned you together for the last time. The vision we cherished of a free & independent country has vanished and that country is now the spoil of a conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to our surrendering it to our enemies. I am no longer your commander. After an association of more than two eventful years, I part from you with a just pride in the fame of your achievements & grateful recollections of your generous kindness to myself. And now, at this moment of bidding you a final adieu, accept this assurance of my unchanging confidence & regard. Farewell!

The Rangers broke ranks to make their individual goodbyes, and then, as they had done so often, melted away into the morning fog.

In addition to the Ford Dealership, that event is the other thing for which Marshall, VA, is remembered. I could leave it at that, but I won’t.

By way of epilogue, Mosby had to hide out in Lynchburg on the run until General Grant interceded to grant him parole. After the war, along with General James Longstreet, Mosby became the object of contempt from former Confederates when he became a Republican. He had also struck up an enduring friendship with Grant, possibly sparked by his kindness at the end of the conflict. He even served as a campaign manager for one of Grant’s Presidential runs.

Mosby later had a distinguished record of service for the Union he had fought so successfully. He had service as the American Consul in Hong Kong, and senior positions in the Interior and Justice Departments. John Mosby died in 1916 at the age of 82. The Marshall Ford dealership had been operating for over a year at the time.

There is no record that he ever rode in one. Summing up his view of war, Mosby wrote: Of his exploits in the war, he wrote “It is a classical maxim that it is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country; but whoever has seen the horrors of a battlefield feels that it is far sweeter to live for it.”

It is a little more elegant than George Patton’s line about making the other son-of-a-bitch die for his country, but I think they both agree.

(Mosby Marker is located at the intersection of West Main Street and Frost Street. It is in the side yard of the Marshall National Bank and Trust. Image courtesy of Craig Swain).

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303