(The fabulous Gayoso Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. The was built overlooking the Mississippi River in 1842 and became a Memphis landmark until it burned in 1899. The original Gayoso House was a first class hotel, designed by James H. Dakin, was appointed with the latest conveniences, including indoor plumbing with marble tubs, silver faucets and flush toilets. Uncle Patrick could not afford to stay there, but the hotel was the nexus of social life in the city in the 1860s).

Note: Uncle Patrick is determined to get the personal effects of his fallen Colonel to his family. In so doing he encounters kindness and deceit in the border country in Tennessee and Kentucky. Can he achieve his mission? There are Unionists, Copperheads and Rebels aplenty along the rivers that were the lifeblood of the Upper South, torn by the great Civil War.

“I had a letter of introduction to Col. Walker, of Memphis, in my pocket. The letter had been given to me by his son, who was a prisoner on board the Yankee boat. As I was not acquainted with the town, I decided to call on Colonel Walker at once. I went to the Gayoso House, the town’s luxurious hotel built by Robertson Topp and considerably enlarged before the war.

There, I asked a hack driver if he knew where Col. Walker lived. He said: “Yes, sir.” I jumped into his hack and told him to take me there, and in a few minutes I was ringing the bell at the Walker residence. Mrs. Walker came to the door. She told me that her husband was away, so I handed her the letter from her son. She read it over three times, but said she could do nothing for me, as her husband had taken the oath of allegiance to the North.

I did not blame her any, for my appearance was not calculated to make a favorable impression. I bade her good-night and walked out the gate. She stood and watched me out of sight

The hackman was waiting for me at the gate. I asked him the amount of his bill, and he said “One dollar.” I had just twenty-five cents, but he did not know but what I was a millionaire; so I told him to take me back to the Gayoso and make it two dollars. On the way back I slipped out of the hack, and the poor Jehu* found himself minus his fare.

For once I was out on the beat, and I headed for cheap quarters. Down on the levee I found a place where they kept boarders and lodgers, and there was a saloon attached. I went in and called for a drink and a cigar, for which I handed up my last quarter in greenbacks. I put on a bold front and told the barkeeper that I would like to have a bed for the night and would want my breakfast very early in the morning. He said: “All right young man; go back there and tell Maggie to show you a bed.” He was playing right into my hand, and I followed his instructions. I found Maggie in the rear of the house, and delivered the barkeeper’s message.

She said she “thought everybody knew where his bed was,” and while I waited for her to locate me I located the cupboard and all the exits. I paid my respects to their larder later in the evening, and was up and away by day-break, too early for any one to be down to collect my bill.

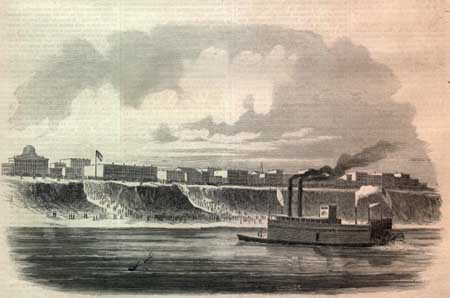

(Memphis Waterfront in the Civil War. Image from Harper’s Weekly.)

I went down by the levee, rolled up my sleeves, and mingled with the roustabouts. I decided that I would learn what I could from them, and I found that one Father Ryan, a Catholic priest, had been arrested on two occasions for his rebellious sentiments. I decided to call upon him, as I had considerable Confederate money sewed in the waist of my pantaloons, and I thought he would be able to tell me where I could sell some of it.

I found him at his residence, and walked into his room without being announced. I attempted to state my business, but before I could do it he interrupted me with the declaration that he was a loyal citizen and that he could do nothing for me. I was determined that he should hear my story, and was confident that he would not report me, and then, too, I wanted to satisfy him that I was worthy of trust.

I pulled out Col. McGavock’s watch and showed him the name engraved upon it, and showed mm the Colonel’s ring also. He became interested, and told me that he had seen an account of the Colonel’s death in the papers.

Just at this juncture the doorbell rang. Father Ryan went to the door himself, and who were there but two Yankee officers? I tell you he was scared, but he was brave and cool about it. He ushered the callers into the parlor, and then he slipped tack and told me that they were evidently after me. He was as white as a sheet and he trembled as he told me to get out the back way. He closed the door on me and went tack to his guests. I hesitated and wondered how any one could know that I was there, and came to the conclusion that I would wait and find out if they were really after me before I went on running, so I slipped back into the house and into the next room to the parlor, where I could be in earshot, and I soon found out that they were on an entirely different mission. I peeped through a crack in the door at them.

They visited for about half an hour; and after Father Ryan saw them out on the pavement, he heaved a sigh of relief that could be heard all over the house. He started back through the hall as if he were going to look out through the rear door, and was very much surprised when I came out and asked him if he was not mistaken about the Yanks being after me. He replied: “I was, thank God, I have had enough of trouble; and when you first spoke to me, I thought you were a spy. The town is full of them. But from your looks I am satisfied now that you are all right. Tell me what you want.”

I told him that I had a large sum of Confederate money and would like to exchange some of it for greenbacks. He thought for a few minutes, then put on his hat and told me that I could go out the back way and he would go out the front way, and I must follow him at a distance.

I carried out his instructions. We went three blocks in the direction of the river and entered a wholesale house. I followed him tack through the house and into the office in the rear. After we got in, he closed the door and introduced me to two gentlemen who were sitting there. He stated my business to them. They declared that they did not have a cent and did not know I where I could dispose of any of my Confederate money. Those gentlemen discredited my story. I shook hands with Father Ryan, thanked him for his kindness, and went on.

It was about nine o’clock when I started toward the river again; and as I stopped on the corner of the street to get my bearings, who should I see coming up the street right by me but Capt. Neff and the Colonel who commanded the fleet of transports.

They were deeply engaged in conversation, and I turned my back toward them and began making marks with a bit of rock on the brick wall. They passed without recognizing me, and you can depend upon it that I was not long making tracks away from them and that neighborhood. I stopped on a comer near the wharf trying to hear something that might be of interest to me. A number of men and women were there gazing at the transports up the river. Many of the prisoners on those boats had relatives in Memphis.

While I stood there I heard two men talking very earnestly. I knew that the time had come for me to lay manners aside, and so I listened deliberately to their conversation. They were Rebel sympathizers; so when they separated, I followed the man who seemed to have the greatest grievance. I caught up with him, asked him to pardon me for having listened to his conversation on the wharf, and told him that I had made my escape from one of the boats, and that before I asked him anything I wanted to prove to him that I was not an impostor.

I showed him Col. McGavock’s watch and ring: and after he had examined them carefully, he exclaimed: “Young man, you will be arrested!” He asked me if I knew Dr. Grundy McGavock, the Colonel’s brother. I told him that I did not. He hesitated awhile, then he looked me straight in the face and told me that he was Prof. Eldridge (I think it was Eldridge), of the Memphis Female Academy.

I knew that this man believed me, and I determined to do whatever he advised. He made me promise that I would not mention his name, and then he directed me to go out Adams Street until I came to the bridge, and then to go into the first house on the left-hand side of the street and ask for Mr. McCoombs. “Show him that watch and he will take care of you,” he said as he shook hands with me.

I went out Adams Street as he directed and rang the bell at the first house beyond the bridge. A young lady answered. I had never seen her before, and yet I knew her, and knew also that I was among friends. I asked her if she was not Miss Kirtland. She said that she was.

The resemblance between her and her brother, Lieutenant Tom Kirtland, of my regiment, was pronounced. I asked her if Mr. McCoombs was at home. She said he lived in the next house. The lady who came to the door at the next house told me that Mr. McCoombs was at the cotton gin, but for me to have a seat and wait for him, as he would soon be coming in to dinner. When he came, I showed him Col. McGavock’s valuables and told him about the Colonel’s death. He was very much affected, and we were still talking when the dinner bell rang.

He requested me to wait a minute, and he went into the house and got a coat and a vest that were just my fit and brought along a beaver hat to complete my costume. Then we walked into the dining room, and I was introduced to his wife and daughters as his nephew from Cincinnati. I suppose his wife and daughters thought their Northern kinsman rather a ravenous fellow, and in my heart I blessed the Professor.

After dinner, Mr. McCoombs and I discussed the matter as to what was best to be done. He called in his wife and his daughter. Miss Mollie, and told them the whole story, but cautioned them to say nothing about it to his other daughter, who had a Yankee captain on her string. Mr. McCoombs decided that ft would be best for him to send over into Arkansas for Dr. Grundy McGavock; and as he had to get back to his cotton gin, he turned me over to Miss Molly, who said that I must rest for a while and then we would go out and see the town. In. the meantime, I was to make myself at home.

On the second day after my installation in the McCoomb’s house Mrs. Col. Walker called on me. I do not know how she found out I was there, and I did not ask her. She made all kinds of excuses for what she termed her unkindness to me, but I insisted that she was right about it. She spent the whole afternoon with me, and made many inquiries about her boys. She wanted me to come and make her house my home while I remained in Memphis. I thanked her and told her that I thought I had better stay where I was.

On the third day after my arrival a gentleman came to the front door. From my post in the parlor I heard him say: “I want to see Pat Griffin.” I peeped out and ascertained that it was not a Yankee, and then I went into the hall, met him, and told him that I was Pat Griffin. He shook hands with me and explained that he was the Colonel’s brother, Dr. Grundy McGavock. I knew he was telling me the truth, for he resembled the Colonel in many ways. He told me to tell him everything about the sad happening at Raymond.

When I told him all, I handed over the Colonel’s watch and ring, his money and valuable papers. It was a sad hour for both of us. Dr. McGavock was very grateful, and he pulled out a roll of greenbacks and told me to help myself. I told him I would need very little money, as I intended to make my way through the lines and back to my command in a few days. I took forty dollars from his roll; but he insisted that if I tried to get through the lines I would be caught and I would need all the money I could get, and he pressed several additional bills into my hands. I never saw him again; and yet, if I had needed his assistance in after years, I knew that he would have responded.

On the next day Mrs. Col. Walker came to see me again and brought me a valise full of clothes. In this collection there was a handsome suit that she was sure would fit me. I assured her that I was very thankful for all these gifts, but that I expected to do considerable walking in the near future and must be as light as possible for die road. She seemed to feel hurt because I would not take the clothing, and we finally compromised by my taking the fine suit of clothes. I put them on the next morning, and was so fine I hardly knew myself.

I took the advice of other heads and did not attempt to go through the lines at Memphis, as the woods all around were said to be deeply infested with Yankees.

I thanked my friends, the McCoombses, for their kindness to me; and after bidding them good-by, I procured a ticket via boat to Louisville.

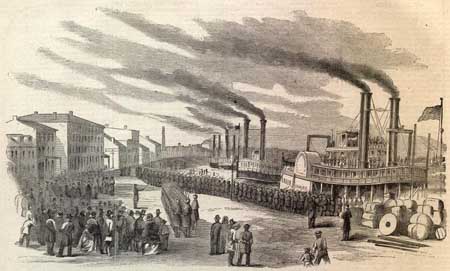

(The waterfront at Louisville in the 1860s. Image from Harper’s Weekly Illustrated, “The Journal of Civilization.”)

I arrived at Louisville in the latter part of June, 1863. The first man I saw that I knew in Louisville was “Shorty” L, who had deserted at Fort Henry. He pretended that he did not know me, but I reminded him that he knew me very well down at Fort Henry a year gone.

I went to the Gate House and met Dr. Cheatham, who was stopping there. Later, I met a member of my company who had taken the oath at Camp Douglas. He invited me to go home with him, and I did. I had known him when we were children and knew his mother and sister, so did not fed any uneasiness in going to their home.

On the next day I hired out to a government boss, who was going to Nashville with a train toad of men to be distributed on the different jobs of work the government was interested in. In a room on Main Street, near Fifth Street, I met the crowd of fifty men who were going down. I was going to Nashville, but all at once I felt sick.

We felt into tine and marched off two and two toward the Louisville and Nashville depot. I finally became so sick that I had to fall out of line, and I sat down on the curbstone. I hailed the first hack that came that way and told the driver to take me tack to my friend’s house. Arriving there, I went to bed immediately. The next morning I had a breaking out all over my hands and face, and the old doctor who was called in pronounced it smallpox. My friend’s mother said that she and all of her children had bad the disease and she had no fear of it.

She told the doctor that I was a stranger and far from home, and she would rather that he did not report my case. He was a good old Rebel, and he was glad to do anything he could to favor me. I got along nicely, and had no visitors with the exception of a Yankee lieutenant and two privates.

They came to the house one day and asked my friend’s mother if she was not harboring a Rebel. She said there was no one in the house save a friend who was very sick. They insisted on seeing me, and she pointed to the door of the dark room where I was. I pulled the cover up over my head and pretended to be asleep. The lieutenant called for a light. He pulled the quilts back and held the lighted candle close to my face.

One look was sufficient to terrify them. He and his escort left there at a double-quick march, and I was left to my recuperation, and the prospect of the long road back to the Bloody Tinth

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Note: * Jehu was the tenth king of Israel. Uncle Patrick may be using an ethnic slur.